Prospective Trial of Osteoarthritis Knee Treatment with Growth Factor Concentrate Therapy for its Efficacy and Safety: ‘Progress’ Trial

ABSTRACT

Osteoarthritis is debilitating not only because it causes pain and limits mobility, but because it can slowly get worse over time. Traditionally, treatment options have included lifestyle modifications, pain management, and corticosteroid injections, with joint replacement reserved for those who have exhausted nonsurgical measures. More recently, hyaluronic acid, micronized dehydrated human amniotic/chorionic membrane tissue, and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections have started to gain traction. PRP has been shown to have both anti-inflammatory effects through growth factors such as transforming growth factor-β and insulin-like growth factor 1. Multiple studies have indicated that PRP is superior to hyaluronic acid and corticosteroids in terms of improving patient-reported pain and functionality scores. In this study 42 patients were recruited and administered 1-3 doses of growth factors isolated from their blood. 6-month follow-up VAS and OKS scores were compared to baseline scores. We found that there is a significant improvement in pain and joint function after 3 doses. The effect was persistent after completion of therapy, suggesting longer lasting effects.

KEYWORDS

Osteoarthritis; Visual analogue score; Oxford knee score; Growth factor concentrate; PRP

ABBREVIATIONS

PRP: Platelet Rich Plasma. VAS: Visual Analogue Score. OKS: Oxford Knee Score. GFC: Growth Factor Concentrate. NSAIDs: Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs. OA: Osteoarthritis. GFs: Growth Factors. SD: Standard Deviation. GI: gastrointestinal

INTRODUCTION

Osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the common musculoskeletal degenerative disorder. Globally, knee OA is responsible for 85% of total OA burden. By 2020, OA is expected to be the 4th leading cause of years lived with disability worldwide [1]. In India, reported prevalence of OA in adults aged 40 years and above is 28.7%. Pain associated loss of daily activities has been reported in 25% patients with OA [2,3]. Pharmacological treatments such as acetaminophen, oral and topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are advised for the management of knee OA [4]. However, the magnitude of analgesic effect of NSAIDs reduces over time. Higher risk of gastrointestinal (GI) effects including limits the adherence to therapy [5,6]. Additionally, risk of cardiovascular events with use of NSAIDs remains a major concern [7,8]. Among other treatments, persistent use of intraarticular corticosteroid injections is associated with significantly greater cartilage volume loss [9]. Though tumor necrosis factor-alpha [10-12], has been evaluated in some studies, they are not currently advised in routine. As available therapies are aimed at alleviating pain only, there is pressing need of newer, effective and safe therapeutics that can target the disease pathophysiology.

As loss of bone-cartilage homeostasis is central to the development of OA, therapies which provide effective pain relief, delay the progression disease and improve function are necessary [13]. Use of platelet rich plasma (PRP), an autologous plasma suspension of platelets with platelet concentration higher than in physiological blood contains various growth factors (GFs) that are released after the PRP injection and help in regenerative process in OA [14]. A metanalysis of randomized controlled trials with PRP in knee OA identified that compared to intraarticular hyaluronic acid or saline injection, intraarticular PRP was associated with effective for pain relief and functional improvement at 12 months post-injection [15]. Also, the effects of PRP are independent of level of cartilage damage [16]. This indicates PRP is a promising therapy for knee OA Also, proposition for consideration of PRP as a first choice in knee OA is suggested by some investigators [17]. However, one need to be overcome certain limitations of PRP. There are no fixed protocols and high inconsistency has been reported in preparation of PRP [18]. Also, the release of growth factors is unsure in conventional PRP preparation. In view of this, Wockhardt’s regenerative medicine department & research laboratory devised the specialized growth factor concentrate kits to release various growth factors from platelets granules. The activation of platelets is performed before the centrifuge which helps is effective release of growth factors from the platelet granules. The final output obtained is devoid of red cells and white cells. To assess the efficacy of this growth factor concentrate (GFC) derived from the activation of platelet in novel, kits, we performed this observational study in patients with mild to moderate knee OA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Setting

This study was conducted at an orthopaedic center providing tertiary care services catering to the urban and semi-urban population.

Study Design

This was a single centre, prospective, open-label study conducted in patients suffering from knee OA.

Study Population

In this study, patients with either unilateral or bilateral knee OA were screened for enrolment. The inclusion criteria were patients with age 18 years and above, either gender, otherwise healthy patients suffering from knee OA related pain (mild to moderate severity) and/or functional abnormalities and willing to participate in the study. Patients with active infections, any malignancy, any comorbid conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, thyroid disorders, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, etc., history bleeding disorders or blood dyscrasias, haemoglobinopathies, or leukemia, and current or past systemic diseases causing immunocompromised state that could affect the healing process in tissues were excluded. Also, pregnant females and lactating mothers were excluded.

Study Intervention

Patients who satisfied above criteria were further subjected to treatment with growth factor concentrate (GFC) injections. GFC in novel technique of extracting high concentration of growth factors from platelets that are essential in tissue regeneration and repair. This latest therapy has been researched and engineered by Wockhardt’s regenerative medicine department & research laboratory. The proprietary platelet activator is used in specialized kits, to release various growth factors from platelets granules. The GFC differs from platelet-rich plasma therapy is that the activation of platelets is done before centrifugation. This ensures minimal platelet loss, release of maximum number of growth factors from platelet granules without red cells and white cells in the final output. Preparation of GFC was done in four steps as below.

a) Step 1 - Collection of blood: 4 ml of patient’s peripheral blood

in was collected in GFC tube

b) Step 2 - Activation of platelet and release of growth factors

(GF): Blood was mixed by gently inverting the blood filled GFC tube

for 6 to10 times and kept straight for 30 mins. This allows activation

of platelets by Wockhardt’s proprietary platelet activating solution

present in tube causing releases GFs from α-granules of platelets.

c) Step 3 - Separation of GFC: GFC tube was then centrifuged at

3400 rpm for 10 min (300g). This allows separation pure GFs from rest

of blood component (Figure 1)

d) Step 4 - Collection of GFC: GFC was then collected by Inverting

the tube. A needle was then inserted through the cap such that the tip of

the needle was just under the cap to allow maximum recovery of GFC.

e) Application of GFC: Nearly 2ml of GFC was collected is ready

for the use.

Treatment Schedule

With GFC, three doses treatment was planned. Each dose of GFC was separated by one-month duration. In each knee, two ml of GFC was injected under all aseptic precautions at visit 1 (baseline), visit 2 (1 month), and visit 3 (2 months). The follow-up was scheduled at one month after completion of three doses (visit 4-3 months from baseline) and at 6 months from baseline (visit 5). No other treatment such as NSAIDs and chondroprotective supplements were allowed during the study. If required, paracetamol was permitted during the study. However, it was discontinued 72 hours before each follow-up assessment.

Study Assessments

All patients were subjected to assessment of pain by visual analogue scale (VAS) score at each visit [19]. Patients were asked to rate the level of pain on visual scale numbered from 1 to 10. Rating from the patients was then recorded in patient files. Patients pain was grouped in three categories based on VAS score as mild (VAS score ≤3), moderate (VAS score 4 to 6) and severe (VAS score ≥7) [20].

Oxford knee score (OKS) [21] was administered to determine the disease status. It is easy-to-use, disease-specific and reliable score. Originally designed for the assessment of joint replacement, the OKS is also used for assessing impact of treatment [22].

OKS contain 12 questions. Response to each question involves one of the five categories with score from 1 to 5 with most to least difficulty or severity. The responses are combined to produce final score which ranges from 12 (most difficulties) to 60 (least difficulties) [21,22].

Outcomes Measures

Change in VAS score and OKS were the efficacy outcomes measures. Clinical safety was assessed in all patients.

Stastical Analysis

Data from patient case files was transcript in a structure case record proforma and then entered in a Microsoft spreadsheet and was analysed with the same. Descriptive statistics were derived. Categorical data was presented as frequency and percentages and continuous data was presented as mean and standard deviation. Student t-test was applied to determine the differences in VAS score and OKS from baseline. P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all comparisons.

RESULTS

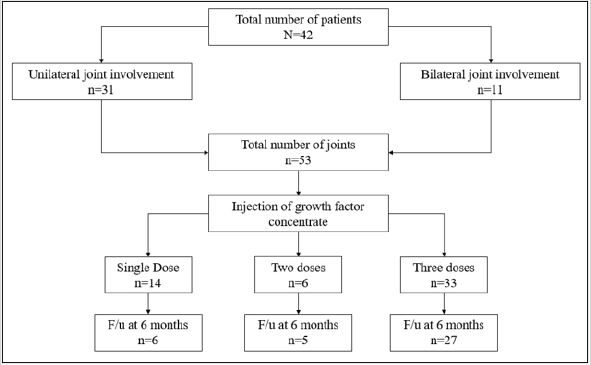

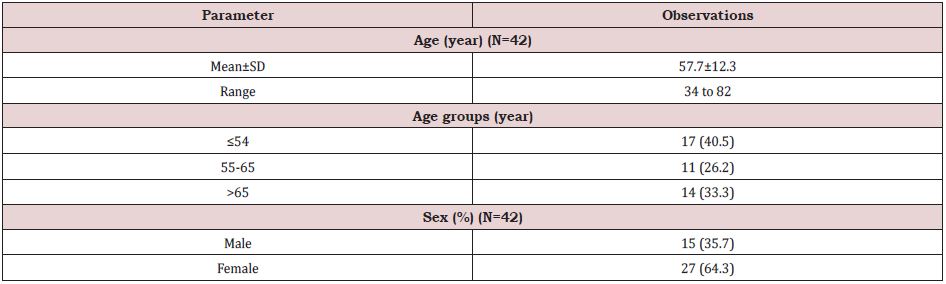

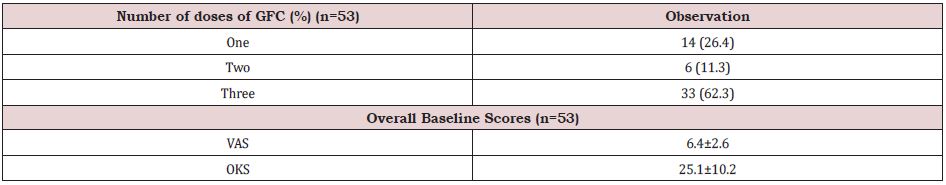

In this study, we enrolled 42 patients of which unilateral knee OA was present in 31 patients and 11 patients had bilateral knee OA. Therefore, total number of joints assessed in final analysis were 53. (Table 1) shows the baseline characteristics of study population. Mean age of the patients was 57.7±12.3 years and it ranged from 34 to 82 years. One third of them were the elderly population (age >65 years). By gender, there were 64.3% females and 35.7% males. From the planned three doses, 62.3% knees received all three doses whereas 26.4% and 11.3% knees received took only single and two doses respectively. At 6 months, data of six, five and 27 knees were available from single, two and three doses group respectively. In three dose group, 3 patients were lost to follow-up and two had total knee transplant and therefore were excluded from the analysis of data of visit at six months (Table 2).

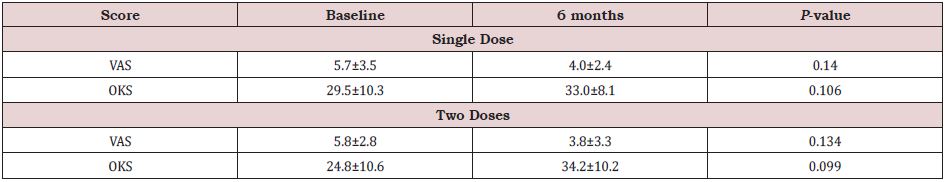

Among patients who had single, or two doses of growth factor concentrate, changes in VAS score and OKS from baseline to six months are shown in (Table 3). In knees treated with single dose, only six knees were followed up at 6 months. Compared to baseline, there was non-significant but numerically higher improvement in VAS score (p=0.140) and OKS (p=0.106) at 6 months in knees treated with single dose. Similarly, no significant difference in the two scores was found in patients receiving two doses (p=0.134 and p=0.099 for VAS and OKS respectively).

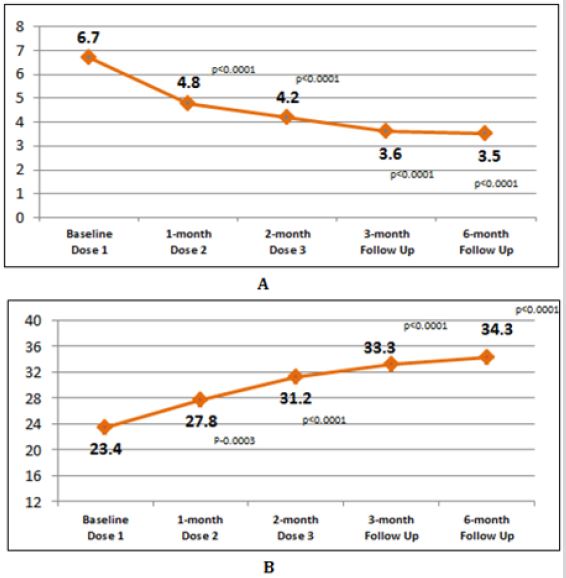

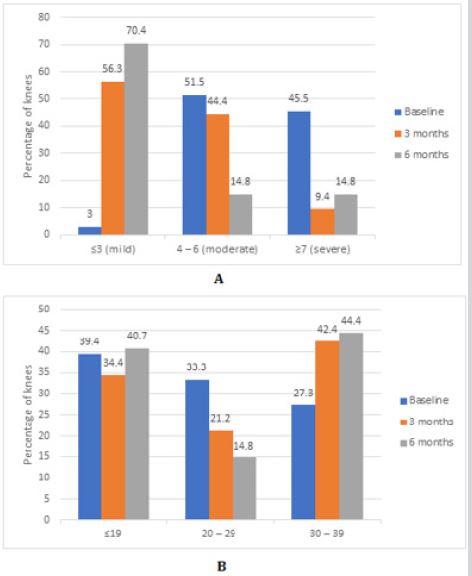

Among total knees treated with three doses of the GFC, followup data of 32 knees at 3 months and 27 knees at 6 months were analyzed. Mean changes in two scores at different visits are shown in (Figure 2). After a first dose, mean VAS score reduced significantly from 6.7±2.1 at baseline to 4.7±2.2 before administration of second dose (p<0.0001). Significant reduction was seen at the administration of third dose also (p<0.0001). At 3 months and 6 months follow-up, mean VAS score was 3.6±2.2 and 3.5±2.3 respectively. The reduction in VAS score from baseline to 4 and 6 months was statistically significant (p<0.0001 for both comparisons). Similarly, increment in OKS from baseline (23.4±10.0) to 3 month (33.3±9.0) and 6-month (34.3±8.7) follow up was statistically significant (p<0.0001 for both comparisons). Distribution of total knees according to pain severity and functional assessment at different visits after three doses is shown in (Figure 3). Proportion of knees with moderate to severe pain reduced and those with mild pain (VAS score ≤3) increased. Similarly, proportion of knees with OKS score 30 to 39 increased from baseline to 6 months. All the injections were well tolerated. No adverse safety concerns were identified during the study period [23].

DISCUSSION

Our study identifies that with three doses of GFC there is significant improvement in pain and function of knee joints with OA as reflected by significant reduction in VAS score and improvement in OKS score. The benefits were evident as early as 1 month after the first injection and were persistent over 6 months. Even after completion of treatment after third injection, the benefits persisted till 6 months. Though no observations were made after 6 months, there is a greater likelihood of persistent effect. This is strongly supported by the finding or metanalysis of RCTs of 10 studies involving 1069 patients. It has been reported that at 12-months post-PRP injection, there was significant pain reduction and improvement in function compared to saline or hyaluronic acid [15]. This is probably the result of growth factors from platelets promoting biological healing and regenerative effects [24]. A three-dose protocol employing PRP injection was found to be effective in reducing pain, improving function and quality of life in all grades knee OA [25]. Considering this, our finding of trend towards non-significant reduction in VAS score and improvement in OKS with single and two injections even employing one or two injections of GFC helps in improving biological parameters in knee. Consistent with this finding, [26] reported that single injection of large volume of very pure PRP resulted in significant pain relief and functional improvement. The non-significant results obtained with one or two injections in our study were because of small number of patients receiving them and even smaller number of them following 6 months. But, when the relatively larger sample was assessed as in three injection group, we found significant results consistent with discussed studies. Consistent results have also been demonstrated in studies from India. [27]. demonstrated that compared to saline treatment, PRP treatment with either single injection or two injection given 3 weeks apart were associated with significant improvements in joint pain and function.

When looked at severity of pain at baseline, 97% of the patients were in moderate to severe pain. With GCF injections, proportion of patients with moderate to severe pain reduced and effect persisted till 6 months. Consistent with our results, demonstrated that after 3 injections of PRP three weeks apart in patients with severe knee OA (VAS score >4 or loss of joint range of motion), there was significant reduction in pain along with improved physical function and quality of life [28]. Improvement in OKS occurred simultaneously suggesting therapeutic effect of GFC. Increase in proportion of patients with higher OKS score indicates that the GCF produced regenerative effects in knee. It is emphasized that the efficacy of PRP doesn’t depend on the level of cartilage damage. This was proved by demonstrating no correlation between the degree of cartilage damage measured by the WORMS (Whole-Organ magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) Score) score of knee OA and benefits of PRP [16]. Therefore, PRP therapy can be considered in any level of severity of joint disease. Beneficial effects reported in the meta-analyses [15,29] confirm that PRP therapy is efficacious and safe in management of knee OA and can be prescribed to patients with any level of severity of the disease. Further, the efficacy in reducing VAS score better than intra-articular steroid injections over 6 months suggests PRP can sustain better effects in patients with knee OA than current treatments. Though some investigators reported mild complications such as nausea, dizziness with use of PRP [27], the safety and tolerability of GFC injections assessed in our study was excellent. No untoward effects were reported in any of the patients.

We had some limitations in this study. Comparison with control treatment would have provided better insights on results. Longer follow-up studies would confirm the long-term effects of GFC in knee OA. Future studies using modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging to establish changes in cartilage, bone and other joint structures would provide better mechanistic insights. However, our study provides first evidence with use of novel GFC preparation kits and therefore laid down foundation for future studies with this new methodology of preparing GFC.

CONCLUSION

With use of novel, growth factors concentrate therapy, we found that there is significant improvement in pain & joint function after three monthly doses along with excellent tolerability. The effect was persistent even after completion of therapy for another 3 months suggesting longer lasting effects. The results are consistent with those observed with PRP. It requires further confirmation of results in a large, double-blind, controlled trial.

REFERENCES

- Hunter DJ, Bierma Zeinstra S (2021) Osteoarthritis. The Lancet 393(10182): 1745-1759.

- Pal CP, Singh P, Chaturvedi S, Pruthi KK, Vij A, et al. (2016) Epidemiology of knee osteoarthritis in India and related factors. Indian J Orthop 50(5): 518-522.

- Chandra D, Rastogi A (2017) Osteoarthritis.

- Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, Benkhalti M, Guyatt G, et al. (2012) American college of rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 64(4): 465-474.

- Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, Zhou M, Mcalindon TE, Bannuru RR, et al. (2020) Duration of symptom selief and early trajectory of adverse events for oral NSAID s in knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Arthritis Care Res 72(5): 641-651.

- Schmidt M, Sørensen HT, Pedersen L (2018) Diclofenac use and cardiovascular risks: series of nationwide cohort studies. BMJ 362: k3426.

- Cooper C, Chapurlat R, Al Daghri N, Herrero Beaumont G, Bruyère O, et al. (2019) Safety of oral non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in osteoarthritis: what does the literature say? Drugs Aging 36(Suppl 1): 15-24.

- Zeng C, Wei J, Persson MSM, Sarmanova A, Doherty M, et al. (2018) Relative efficacy and safety of topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies. Br J Sports Med 52(10): 642-50.

- McAlindon TE, LaValley MP, Harvey WF, Price LL, Driban JB, et al. (2017) Effect of intra-articular triamcinolone vs saline on knee cartilage volume and pain in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 317(19): 1967-1975.

- Maksymowych WP, Russell AS, Chiu P, Yan A, Jones N, et al. (2012) Targeting tumour necrosis factor alleviates signs and symptoms of inflammatory osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Res Ther 14(5): R206.

- Ohtori S, Orita S, Yamauchi K, Eguchi Y, Ochiai N, et al. (2015) Efficacy of direct injection of etanercept into knee joints for pain in moderate and severe knee osteoarthritis. Yonsei Med J 56(5): 1379-1383.

- Wang J (2018) Efficacy and safety of adalimumab by intra-articular injection for moderate to severe knee osteoarthritis: an open label randomized controlled trial. J Int Med Res 46(1): 326-334.

- Hussain SM, Neilly DW, Baliga S, Patil S, Meek R (2016) Knee osteoarthritis: a review of management options. Scott Med J 61(1): 7-16.

- Foster TE, Puskas BL, Mandelbaum BR, Gerhardt MB, Rodeo SA (2009) Platelet-rich plasma: from basic science to clinical applications. Am J Sports Med 37: 2259-2272.

- Dai WL, Zhou A G, Zhang H, Zhang J (2017) Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthroscopy 33(3): 659-670.

- Burchard R, Huflage H, Soost C, Richter O, Bouillon B, et al. (2019) Efficiency of platelet-rich plasma therapy in knee osteoarthritis does not depend on level of cartilage damage. J Orthop Surg Res 14(1): 153.

- Cook CS, Smith PA (2018) Clinical update: why PRP should be your first choice for injection therapy in treating osteoarthritis of the knee. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 11(4): 583-592.

- Chahla J, Cinque ME, Piuzzi NS, Mannava S, Geeslin AG, et al. (2017) A call for standardization in platelet-rich plasma preparation protocols and composition reporting: a systematic review of the clinical orthopaedic literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am 99(20): 1769-1779.

- Haefeli M, Elfering A (2006) Pain assessment. Eur Spine J 15(Suppl 1): S17-S24.

- Eliav E Gracely RH (2008) Measuring and assessing pain. Orofacial pain and headache. Elsevier Health Sciences Philadelphia 1:45-56.

- Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Murray D, Carr A (1998) Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 80(1): 63-69.

- Murray DW, Fitzpatrick R, Rogers K, Pandit H, Beard DJ, et al. (2007) The use of the Oxford hip and knee scores. J Bone Joint Surg Br 89(8): 1010-1014.

- Collins NJ, Misra D, Felson DT, Crossley KM, Roos EM (2011) Measures of knee function: international knee documentation committee (IKDC) subjective knee evaluation form, knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS), knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score physical function short form (KOOS-PS), knee outcome survey activities of daily living scale (KOS-ADL), lysholm knee scoring scale, oxford knee score (OKS), western Ontario and McMaster universities osteoarthritis index (WOMAC), activity rating scale (ARS), and tegner activity score (TAS). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 63 Suppl 11(0 11): S208-228.

- Dhillon MS, Patel S, John R (2017) PRP in OA knee-update, current confusions and future options. SICOT-J 3: 27.

- Fernández Cuadros ME, Pérez-Moro OS, Albaladejo-Florín MJ (2018) Effectiveness of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) on pain, function and quality of life in knee osteoarthritis patients: a before-and-after study and review of the literature. MOJ Orthop Rheumatol 10(3): 202-208.

- Guillibert C, Charpin C, Raffray M, Benmenni A, Dehaut FX, et al. (2019) Single injection of high volume of autologous pure PRP provides a significant improvement in knee osteoarthritis: a prospective routine care study. Int J Mol Sci 20(6): 1327.

- Patel S, Dhillon MS, Aggarwal S, Marwaha N, Jain A (2013) Treatment with platelet-rich plasma is more effective than placebo for knee osteoarthritis: a prospective, double-blind, randomized trial: a prospective, double-blind, randomized trial. Am J Sports Med 41(2): 356-364.

- Akan Ö, Sarıkaya NÖ, Koçyiğit H (2018) Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma administration in patients with severe knee osteoarthritis: can platelet-rich plasma administration delay arthroplasty in this patient population? Int J Clin Exp Med. 11(9): 9473-9483.

- Chang KV, Hung CY, Aliwarga F, Wang TG, Han DS, et al. (2014) Comparative effectiveness of platelet-rich plasma injections for treating knee joint cartilage degenerative pathology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 95(3): 562-575.

Article Type

Research Article

Publication history

Received Date: April 06, 2022

Published: June 01, 2022

Address for correspondence

Anuka Sharma, Wockhardt Hospitals Limited Manager- Department of Regenerative Medicine, India

Copyright

©2022 Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science, All rights reserved. No part of this content may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means as per the standard guidelines of fair use. Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

How to cite this article

Anuka S, Vijay S, Parag RG, Arefa P, Ulka S, Mudit K. Prospective Trial of Osteoarthritis Knee Treatment with Growth Factor Concentrate Therapy for its Efficacy and Safety: ‘Progress’ Trial. 2022- 4(3) OAJBS.ID.000455.

Figure 1: Study flow chart.

Figure 2: Visit-to-visit change in two scores after 3 doses.

A: Change in mean VAS score,

B: Change in mean OKS.

Figure 3: Proportional changes in two scores in three doses group.

A: Proportional changes in VAS score.

B: Proportional changes in OKS.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics.

Table 2: Number of doses in different knees and baseline scores.

Table 3: Changes in scores after single dose and two doses.