Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia, What’s New?

ABSTRACT

Background: Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) is an arrhythmia originating in or above the atrioventricular (AV) node and is

defined by a narrow complex (QRS < 120 milliseconds) at a rate > 100 beats per minute (bpm). The incidence of AV nodal re-entry

tachycardia is 35 per 10,000 person-years or 2.29 per 1000 people.

Methodology: A systematic review was carried out through various databases from January 2015 to February 2022, the search

and selection of articles was carried out in journals indexed in English.

Results: In the United States, it has been identified that the prevalence of supraventricular tachycardia ranges from 0.2%,

presenting an incidence of approximately 1 to 3 cases per thousand patients. To date this type of condition remains difficult to

manage or treat. Alternative therapies include the use of beta blockers and calcium channel blockers.

Conclusion: This review offers updated and detailed information on the main causes of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia,

as well as its epidemiological aspects, pathophysiological processes, clinical symptoms, and current management

KEYWORDS

Supraventricular tachycardia; Pathophysiology; Diagnosis; Management

ABBREVATIONS

SVT: Supra Ventricular Tachycardia; AV: Atrio Ventricular; AVNRT: Atrioventricular Nodal Re-entry Tachycardia; AT: Atrial Tachycardia; PSVT: Paroxysmal Supra Ventricular Tachycardia

INTRODUCTION

Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) is an arrhythmia originating in or above the atrioventricular (AV) node and is defined by a narrow complex (QRS < 120 milliseconds) at a rate > 100 beats per minute (bpm) [1]. Atrioventricular nodal reentry tachycardia (AVNRT), also known as paroxysmal SVT, is defined as intermittent SVT without triggers and typically presents with a ventricular rate of 160 bpm [1,2]. Patients with antegrade conduction may be at risk of developing pre-excited atrial fibrillation. It is characterized by a wide and irregular QRS of variable duration and morphology due to conduction by the AV node and the pathway at different speeds [2]. Atrial tachycardia (AT) originates within the atrium and is unrelated to the behavior of the AV node. On the surface ECG, the P waves appear monomorphic with a stable tachycardia cycle length, but morphologically distinct from the sinus P wave. There are two mechanisms, focal and re-entrant, with typical atrial flutter being by far the most common AT seen in clinical practice [2,3]. The incidence of AV nodal re-entrant tachycardia is 35 per 10,000 person-years or 2.29 per 1000 people and is the most common non-sinus tachyarrhythmia in young adults. Women are twice as likely to develop paroxysmal SVT compared to men, and older people are five times as likely compared to a younger person [3]. SVT is the most common symptomatic arrhythmia in infants and children. Children with congenital heart disease are at increased risk of SVT. In children younger than 12 years, an accessory AV pathway causing re-entrant tachycardia is the most common cause of SVT [4,5]. Due to the large number of cases that occur due to this pathology, it is convenient to carry out this study, in order to provide updated and accurate information on the main causes of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia, as well as its epidemiological aspects, pathophysiological processes, clinic and current management.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A systematic review was carried out, PubMed, Scielo and ScienceDirect were the main databases used. The collection and selection of articles was carried out in journals indexed in English from 2015 to 2022. 131 original and review publications related to the subject were identified, 20 articles met the inclusion requirements, articles that were in a range not less than the year 2015, that they were full text articles and that they reported on paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT). Articles that did not have sufficient information and that did not present the full text at the time of review were excluded.

RESULTS

Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia

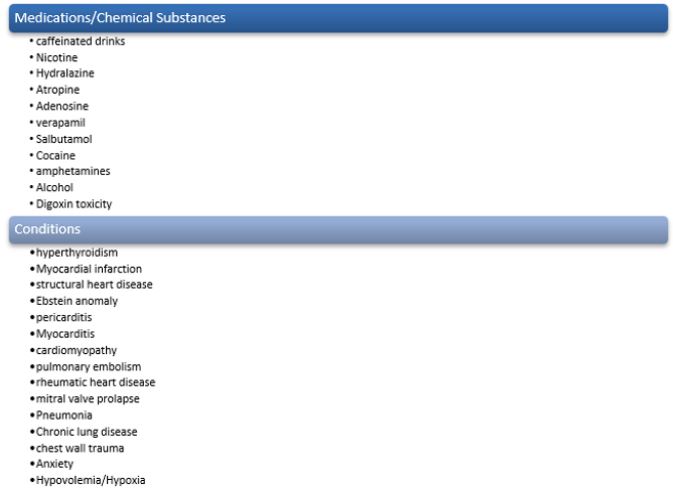

This type of heart condition can occur at any stage of life, both in children and in adults or the elderly. To date this type of condition remains difficult to manage or treat [6]. As is well known, this type of condition can present itself in two clinical forms, one can be asymptomatic, and it can also present symptoms such as intense palpitations [7]. One of the most used methods in the clinic to establish the diagnosis as well as to determine its pathophysiological process are electrophysiological studies [6]. In addition to improving the symptoms of pain or any other symptoms presented by the patient, it is pertinent and advisable to establish the cause. Since numerous conditions and medications can lead to paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia. In Figure 1 we can identify some of the causes, to which this fiction is attributed, or associated [6-8].

Epidemiological Aspects

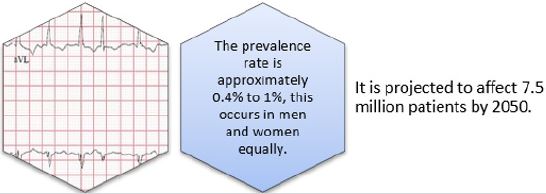

In the United States, it has been identified that the prevalence of supraventricular tachycardia ranges from 0.2%, presenting an incidence of approximately 1 to 3 cases per thousand patients. In Figure 2 we can see the most common type of supraventricular tachycardia [7-10]. The risk of developing Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia was found to be twice as high in women than in men in a population study, with a higher prevalence with age. Atrioventricular nodal re-entry tachycardia is most often found in middle-aged or older patients. While Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia with an accessory pathway is more common in adolescents and its appearance decreases with age [11].

Pathophysiological Process

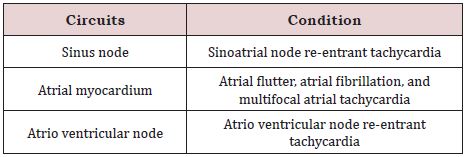

PSVT is often due to different re-entrant circuits in the heart, with less common causes including increased or abnormal automaticity and triggered activity. Re-entrant circuits include a pathway within and around the sinus node, within the atrial myocardium, within the AV node, or an accessory pathway involving the AV node [12]. Depending on the existing circuits, the different types of Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia will be presented, in Table 1 we can identify some examples. [12-15].

Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia Clinic

Depending on the frequency of episodes of this condition and the patient’s hemodynamic reserve, the severity of symptoms will occur. The most frequent symptoms attributable to this condition are dizziness, syncope, nausea, shortness of breath, intermittent palpitations, neck pain or discomfort, chest pain or discomfort, anxiety, fatigue, diaphoresis, and polyuria [14]. Patients with Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia and a known history of coronary artery disease may experience a myocardial infarction secondary to stress on the heart. And if they have a known history of heart failure, they may have an acute exacerbation [15]. To correctly establish the patient’s symptoms, it is recommended to inquire about their medical and cardiac history, the time of onset of symptoms, previous episodes, and treatment. Patients’ current medication list should be obtained. Investigations into participation in physical activities such as exercise or outdoor sports should be conducted, as symptomatic patients avoid such hobbies [16]. To assess the patient’s hemodynamic stability, vital signs (respiratory rate, blood pressure, temperature, and heart rate) must be taken, as well as a complete physical examination [15]. As part of the initial care, the treating physician should consider thyroid function tests, pulmonary function tests, including routine blood tests, and echocardiography [16].

Current Management of Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia

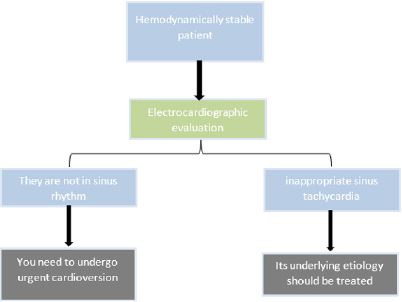

Patients presenting with hypotension, dyspnea, chest pain, shock, or altered mental status are considered hemodynamically unstable and should undergo electrocardiographic evaluation to determine whether they are in sinus rhythm. In Figure 3 we can identify a diagram of the steps to follow [12-16]. For any manifestation of cardiac ischemia, intravenous beta-blockers should be considered. If they have inappropriate sinus tachycardia on the electrocardiogram and are determined to be hemodynamically unstable, treatment with intravenous beta-blockers may be appropriate. If the 12-lead electrocardiogram shows that the rhythm is irregular and there are no P waves, the patient should receive appropriate treatment for atrial fibrillation. If the rhythm on the electrocardiogram is irregular and flutter waves are present, then the patient should be treated for atrial flutter. If the rhythm on the electrocardiogram is irregular and there are multiple P wave morphologies, the patient should be treated for multifocal atrial tachycardia [10]. In patients who are hemodynamically stable and have an electrocardiogram showing a regular rhythm with undetectable P waves, Valsalva maneuvers, carotid sinus massage, or intravenous adenosine may be used to slow the ventricular rate or convert the rhythm to sinus rhythm and so on. help in diagnosis [10-16]. If intravenous adenosine does not work, intravenous or oral calcium channel blockers or beta-blockers should be used. Patients with Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia should also undergo evaluation for any underlying preexcitation syndrome, and patients who fail medical treatment or those who may require radiofrequency catheter ablation should be referred or consulted with a cardiology specialist [17].

DISCUSSION

A study carried out by [18] in which he makes a general description of the diagnosis and treatment. The most common SVTs are tachycardia due to re-entry in the atrioventricular node and atrial tachycardia. The underlying mechanism can be inferred from electrocardiography during the tachycardia, comparing it to sinus rhythm, and evaluating the onset and end of the tachycardia. They further report that alternative therapies include the use of beta blockers and calcium channel blockers [18]. Another study carried out by [19] in which they carry out a systematic review in different databases, in order to identify the most frequent complications attributable to this pathology. These authors report that paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia is associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke. Therefore, when providing management to patients with supraventricular tachycardia, it is always advisable to be alert and attentive to the possible lethal complications that may develop [19]. A strength of the current study is the implemented methodology, regarding the literature search, and steps in the selection of relevant articles, quality assessment and data extraction. However, this study has several limitations, which should be considered, among these are the little evidence from the analysis of clinical trials reporting on the therapeutic approach in patients who develop complications, so more studies are needed to answer these questions.

CONCLUSION

This type of heart condition can occur at any stage of life, both in children and in adults or the elderly. To date this type of condition remains difficult to manage or treat. In the United States, it has been identified that the prevalence of supraventricular tachycardia ranges from 0.2%, presenting an incidence of approximately 1 to 3 cases per thousand patients. The prevalence rate is approximately 0.4% to 1%, this occurs in men and women equally. Depending on the frequency of episodes of this condition and the patient’s hemodynamic reserve, the severity of symptoms will occur. The most frequent symptoms attributable to this condition are dizziness, syncope, nausea, shortness of breath, among others. Alternative therapies include the use of beta blockers and calcium channel blockers.

REFERENCES

- Luca AC, Curpan AS, Miron I, Horhota EO, Iordache AC (2020) Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia in wolff-parkinson-white syndrome in a newborn-case report and mini-review. Medicina (Kaunas) 56(11): 588.

- Shaker H, Jahanian F, Fathi M, Zare M (2015) Oral verapamil in paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia recurrence control: a randomized clinical trial. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis 9(1): 4-9.

- Katritsis DG, Josephson ME (2015) Differential diagnosis of regular, narrow-QRS tachycardias. Heart Rhythm 12(7): 1667-1676.

- Karmegeraj B, Namdeo S, Sudhakar A, Krishnan V, Kunjukutty R, et al. (2018) Clinical presentation, management, and postnatal outcomes of fetal tachyarrhythmias: A 10-year single-center experience. Ann Pediatr Cardiol 11(1): 34-39.

- Brubaker S, Long B, Koyfman A (2018) Alternative treatment options for atrioventricular-nodal-reentry tachycardia: An emergency medicine review. J Emerg Med 54(2): 198-206.

- Upadhyay S, Marie VA, Triedman JK, Walsh EP (2016) Catheter ablation for atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia in patients with congenital heart disease. Heart Rhythm 13(6): 1228-1237.

- Alsaied T, Baskar S, Fares M, Alahdab F, Czosek RJ, et al. (2017) First-line antiarrhythmic transplacental treatment for fetal tachyarrhythmia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 6(12): e007164.

- Balli S, Kucuk M, Orhan BM, Kemal YI, Celebi A (2018) Transcatheter cryoablation procedures without fluoroscopy in pediatric patients with atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia: A single-center experience. Acta Cardiol Sin 34(4): 337-343.

- Mironov NY, Golitsyn SP (2016) Overwiew of new clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of supraventricular tachycardias (2015) of the american college of cardiology/american heart association/society for heart rhythm disturbances. Kardiologiia 56(7): 84-90.

- Voerman JJ, Hoffe ME, Surka S, Alves PM (2018) In-flight management of a supraventricular tachycardia using telemedicine. Aerosp Med Hum Perform 89(7): 657-660.

- Chung R, Wazni O, Dresing T, Chung M, Saliba W, et al. (2019) Clinical presentation of ventricular-Hisian and ventricular-nodal accessory pathways. Heart Rhythm 16(3): 369-377.

- L’Italien K, Conlon S, Kertesz N, Bezold L, Kamp A (2018) Usefulness of echocardiography in children with new-onset supraventricular tachycardia. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 31(10): 1146-1150.

- Ho RT (2017) A narrow complex tachycardia with atrioventricular dissociation: What is the mechanism? Heart Rhythm 14(10): 1570-1573.

- Khurshid S, Choi SH, Weng LC, Wang EY, Trinquart L, et al. (2018) Frequency of cardiac rhythm abnormalities in a half million adults. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 11(7): e006273.

- Katritsis DG, Josephson ME (2015) Differential diagnosis of regular, narrow-QRS tachycardias. Heart Rhythm 12(7): 1667-1676.

- Shaker H, Jahanian F, Fathi M, Zare M (2015) Oral verapamil in paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia recurrence control: a randomized clinical trial. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis 9(1): 4-9.

- Keishi I, Tadashi W, Takahiro N, Masahiro T (2017) A case of lifethreatening supraventricular tachycardia storm associated with theophylline toxicity. J Cardiol Cases 15(4): 125-128.

- Irum D, Steven E, Mark O (2020) Supraventricular tachycardia: An overview of diagnosis and management. Clin Med (Lond) 20(1): 43-47.

- Pongprueth R, Phuuwadith W, Arjbordin W, Patompong U (2019) Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia and risk of ischemic stroke: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Arrhythm 35(3): 499-505.

Article Type

Mini Review

Publication history

Received Date: August 25, 2022

Published: October 07, 2022

Address for correspondence

Carlos Andrés Genes Vasquez, General Physician, Universidad del Sinú, Colombia, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8189-7363

Copyright

©2022 Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science, All rights reserved. No part of this content may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means as per the standard guidelines of fair use. Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

How to cite this article

Carlos AGV, Ferney SCA, Diego ACV, Jhoyner AJF, Karen TVU, et al. Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia, What’s New?. 2022- 4(5) OAJBS.ID.000494.

Figure 1: Main causes of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia.

Figure 2: Atrial fibrillation, the most common type of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia.

Figure 3: Management diagram of the hemodynamically unstable patient.

Table 1: Re-entry circuits associated with different types of Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia.