Knowledge, Beliefs and Preventive Behaviours Regarding Osteoporosis Among Female Health Colleges’ Students at King Abdulaziz University

ABSTRACT

Osteoporosis is a disease in which the density and quality of bones reduce. It is a silent thief, producing no symptoms until a

fragility fracture occurs..

Aim: This study aimed to assess the osteoporosis knowledge, beliefs, and preventive behaviours among female health colleges’

students at King Abdulaziz University.

Materials and Methods: Design: A cross sectional descriptive design. Setting and sample: 299 female students were recruited

from four female health faculties (nursing, dentistry, applied medical and medical rehabilitation sciences) at King Abdulaziz

University in Jeddah.

Tools for Data Collection: Four tools were used including: characteristics assessment questionnaire, osteoporosis knowledge

assessment tool, osteoporosis health belief scale and osteoporosis preventing behaviours survey.

Results: 52.5% of the study participants had moderate level of knowledge regarding osteoporosis with satisfactory level of

knowledge regarding osteoporosis symptoms and risk of fracture (60.4%). While, there was unsatisfactory level of knowledge

regarding osteoporosis risk factors, preventive measures and availability of the treatment (43.4%, 38.3% and 36.6% respectively).

The beliefs of perceived susceptibility and seriousness of osteoporosis were low (53% and 57% respectively). Also, there was

inadequate level of practicing osteoporosis preventive behaviours. Additionally, there were significant positive correlations were

found between physical activity and perceived benefits of physical exercise and calcium intake and health motivation. In addition,

significant negative correlations had been detected between physical activity and both of barriers to exercise and calcium intake.

Finally, there was highly significant positive correlation between students’ knowledge regarding osteoporosis and their health

beliefs. Conclusion and recommendations: Moderate level of students’ knowledge regarding osteoporosis was noted. Susceptibility

and severity perception toward osteoporosis were low. Practices towards preventing osteoporosis were inadequate. Therefore, the

researcher recommended to provide health education and prevention programs about osteoporosis targeted university students to

narrow the gap between knowledge and practices.

KEYWORDS

Health beliefs; Health colleges students; Knowledge; Osteoporosis; Preventive behaviours

INTRODUCTION

Osteoporosis is a disease identified by a reduction in the quality and density of the bones. It is a silent disease, that has no signs until a fragility fracture occurs. McLendon [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines osteoporosis by low bone mineral density (BMD) and established a diagnostic criteria using Dualenergy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) to measure the BMD as a Tscore, where T-score between +1 and −1 is considered normal in young healthy women, T-score between −1 and −2.5 diagnosed as osteopenia and the T- score equal or less than −2.5 diagnosed as osteoporosis WHO [2].

Throughout life, the human skeleton is constantly renewed by remodelling. Bone remodelling is a process where osteoclasts and osteoblasts work. Breaks down (resorption) of the aged bone done by osteoclasts and new bone formation done by osteoblasts Chen et al. [3]; Matsuoka et al. [4].

Besides, growth spurt in height and bone’ structure and composition among the children relatively slow then accelerated suddenly with the onset of puberty. Thereby bone strength influenced then the peak of bone mass reached shortly after the height peak is gained by the age 16 - 19 years. Then, the changes in the total of bone mass between age 30 and menopause appeared to be minimal Weaver et al. [5]; Berger et al. [6].

After achieving the peak bone mass, the resorption and formation remain stable at physiological conditions for one or two decades until age-related bone loss begins. Age-related bone loss is caused by increases in resorptive activity (osteoclasts) and reduced bone formation (osteoblasts). However, when the balance is disturbed, bone architecture or function will be abnormal and bone metabolism diseases, such as osteoporosis will occur Chen et al. [3]; Langdahl et al. [8].

SIGNIFICANCE OF THE STUDY

Since the majority of primary prevention programs for osteoporosis have focused on women in mid-life, a concern is that young adults may not be aware of osteoporosis risk factors and therefore may not be engaging in preventive behaviours Rodzik [8]. Moreover, young adults are a targeted group for osteoporosis prevention because young adulthood is a critical period in which many poor or inappropriate health behaviours are rooted Zarshenas et al. [9]. On the other hand, there is a gap in the literature about the change of health behaviours depending on knowledge and beliefs among young women and it has not been extensively studied Endicott [10].

In 2012, Sadat-Ali et al. [11] estimated the prevalence of osteoporosis for Saudi Arabian women aged more than 50 years to be approximately 34% compared to USA with 10.3%. These alarming figures on the increasing incidence of osteoporosis come at a time when people can easily and effectively implement many effective behaviours in the prevention of osteoporosis. These preventive behaviours decrease the risk of developing osteoporosis by 10-60% DeRuiter-Willems [12]; Krmoyan [13]; Gammage et al. [14]; Gammage [15]. Also, ten percent improvement in bone mass between young people can account for a 50-percent decrease in the risk for bone fracture in later life (US Department of Health and Human Services USDHHS [16].

The International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) in 2019 stated that a 10% increase in peak BMD was predicted to delay the development of osteoporosis by 13 years. Because of this, it is critical that young women become better educated about the risk factors that lead to osteoporosis, because this illness has long term effects on women. In order for women to make choices about prevention, they need to know what osteoporosis is, how to prevent it, and how to perform the preventive behaviours Enteshari- Moghaddam et al. [17]; NIH [18]. Wherefore, knowledge is an important factor affecting health behavior, but many researchers suggest that knowledge merely is insufficient in altering behaviours; and increased knowledge about osteoporosis does not always lead to change in osteoporosis behaviours Ramli et al. [19]; Bilal et al. [20]; De Silva et al. [21]. Therefore, this study was conducted to investigate knowledge about osteoporosis among the female students attending health colleges in KAU and their beliefs about the disease and risk factors in addition to their preventive behaviours. This in turn can lead to evidence-based interventions to raise awareness about osteoporosis and change subsequent beliefs and to make further recommendations and interventions regarding educational programs about osteoporosis for those the young adults females.

AIM OF THE STUDY

This study aimed to assess the osteoporosis knowledge, beliefs, and preventive behaviours among female health colleges’ students at King Abdulaziz University (KAU) in Jeddah.

Research Questions:

This study was conducted to answer the following research questions:

1. What are the prevailing beliefs, level of knowledge and

preventive behaviours among female students attending health

colleges in KAU on osteoporosis prevention activities?

2. What is the relationship between osteoporosis beliefs and

knowledge and osteoporosis preventive behaviours among female

students attending health colleges in KAU?

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Research Design

Cross-sectional descriptive design was used to conduct this study and to answer the research questions.

Research Setting

The current study was conducted at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah and carried out at four female health faculties (faculty of nursing, faculty of dentistry, faculty of applied medical and faculty of medical rehabilitation sciences) during the academic year 1439- 1440 H.

Subjects

A convenience sample of 299 students were recruited from the previously mentioned setting. The sample size was calculated using Raosoft software with the following input; 5.0% margin of error (95.0% confidence level) and 1159 students (faculty of nursing were 370, faculty of dentistry were 385, faculty of applied medical were 272 and faculty of medical rehabilitation sciences were 132) Raosoft Inc. [22]. The calculated sample using Raosoft software were 289 students. Ten students were added over the calculated sample for the possibility of dropout.

Tools for Data Collection

The data was collected using the following four tools:

Characteristics assessment questionnaire: This tool was developed by the researcher based on the review of literatures. It includes questions regarding characteristics (age, gender, height, weight, marital status, educational level, type of college, receiving previous knowledge about osteoporosis and family history of osteoporosis).

Osteoporosis knowledge assessment tool (OKAT): This tool was developed by Winzenberg et al. [23] and translated by the researcher into Arabic language, then revised by 5 experts. It is formed of 20 questions with four basic themes; understanding the osteoporosis symptoms and risk of fracture (Q1,2,8,9&11), osteoporosis risk factors (Q 3,4,5,6,7,12 &18), preventive measures as physical activity and diet to prevent from osteoporosis (Q 10,13,14,15,16,17) and availability of the treatment (Q 19 &20), with ≥ 60% consider satisfactory level of awareness regarding these previous themes. The question responses were either “true”, “false” or “don’t know “ options. The correct answer was given 1 score, while, the incorrect answer and the response for “ don’t know” were given “zero”. The maximum scores for this tool was 20, this score was multiplied by 5 to get 100, then categorized as follow:

Poor for scores less than 40 (< 8 out of 20)

Moderate for scores range from 40-59 (8- 11.9)

Good for scores of 60 or more (≥ 12 out of 20)

Osteoporosis health belief scale (OHBS): This scale was developed by Kim et al. [24] and translated to Arabic language by the researcher, then revised by 5 experts. It involves 42 statements under seven subscales (susceptibility, severity, benefits to exercise, benefits to calcium intake, barriers to exercise, barriers to calcium intake, and health motivation) based on health beliefs model (each subscale involves six statements). A 5-point Likert scale was used to rate each item with 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree. The possible range of scores is between 42 to 210 for the total health belief scale and the possible range for each subscale is 6 to 30 scores. The highest scores indicate strong or high beliefs and the lowest scores indicate poor beliefs about osteoporosis.

Osteoporosis preventing behaviours survey (OPBS): This survey was developed by Doheny [25] and translated to Arabic language by the researcher, then revised by 5 experts. It was consisted of 39 descriptive items that addresses osteoporosis preventing behaviours involving the categories of activities/ exercise, dietary intake of calcium, and other risk factors (smoking, alcohol use, use of hormonal therapy, use of non-hormonal therapy and other medications that affect bone density) for both young and post menopause women. After that, it was modified by Edmonds [26] to eight-items survey only including specific items related to young adults and the other items related to menopause were eliminated.

The survey comprised of eight questions as follows; questions from one to three ask about milk, yogurt and cheese consumption per week in the form of multiple-choice questions with eleven choices. Question four asks about the calcium supplement consumption with responses either “ yes” or “ no”. Questions five and six assess the physical activity performed per week (both weight and non-weight bearing exercises) in the form of multiplechoice question with eight choices.

Questions seven includes a seven-day physical activity recall (7dPAR) which provides details regarding the duration and intensity of physical activity. It is used as a reference for quantifying the types of physical activity by using metabolic equivalent of task (MET) as follow; sedentary behavior (i.e., 1.0-1.5 METs), light-intensity (1.6- 2.9 METs), moderate-intensity (3-5.9 METs), and vigorous-intensity (≥6 METs) activities. The compendium of physical activities was used to code each recorded activity by the participants for analysis and representing the specific activities performed with their respective metabolic equivalent of task (MET) intensity levels. A MET values defined as the ratio of the work metabolic rate to a standard resting metabolic rate (RMR) and is a commonly used method for capturing intensity of the physical activity Ainsworth et al. [27]; Howley [28]. Question eight compares the physical activity in the last week with the activity done in the past three months, with three possible choices: “ more”, “less” or “ about the same”.

Scoring system for osteoporosis preventing behaviours survey: To score the first three questions; the responses denoting less than four serving a week were considered “inadequate intake” and given one score, the responses denoting five servings a week to one serving a day were considered “moderate intake” and given two score while, the responses denoting two to three servings a day were considered “adequate intake” and given three score.

Regarding the scoring of question four, the responses were “yes” or “no”, “yes” was given one score and “no” was given “zero”.

In the question five and six, the responses were scored as follow:

less than 10 minutes per week was given 1 score

10-15 minutes for 1 to 2 times per week was given two score

10-15 minutes for 3 to 4 times per week was given three score

10-15 minutes for 5 to 7 times per week was given four score

20-30 minutes for 1 to 2 times per week was given five score

20-30 minutes for 3 to 4 times per week was given six score

20-30 minutes for 5 to 7 times per week was given seven score

more than 30 minutes per day was given eight score.

The total score of the previous six questions were summed up, the possible score of the total OPBS ranges from 5-26. The higher scores denoting better engagement in good osteoporosis preventive behaviour and vice versa. The 7dPAR was analysed by computing the total MET/minute per week for each participant. According to the world confederation of physical activity (WCPT) in 2018, the current WHO guidelines for adequate level of weekly MET/minute is between 600-1200 MET minutes per week and the new recommendation to gain more health when achieving 3000- 4000 MET minutes per week. The 7dPAR of each subject was analysed by the researcher by assigning the MET value for each activity according to the compendium of the physical activity. Then multiplying it by the total minutes of the self-reported activity. This process was done for every activity listed per day. The weekly MET/ minute was determined by summing up the totals of MET/minute for each day together. The number and percent for each choice in question eight were calculated.

Tools Validity

he Arabic questionnaires were revised by five experts in the field of nursing in faculty of nursing in KAU to test the face and content validity in term of content clarity, relevance, comprehensiveness, representativeness, logical consequence, appropriateness of the content to achieve the study aim and accurateness. The questionnaires were modified according to the experts’ feedbacks (modifications were in the form of rephrasing of some statements).

Tools Reliability

Reliability analysis had been performed for all study questionnaires to test the internal consistency using Alpha Cronbach test. Firstly, osteoporosis knowledge assessment tool (OKAT) reliability analysis for the internal consistency was 0.716 Cronbach Alpha or 71.6% indicating a high internal consistency. Secondly, osteoporosis health belief scale reliability analysis was 0.904 Cronbach Alpha or 90% which indicates excellent internal consistency. Finally, the reliability analysis for the questions related to physical activity was carried out for questions 5 and 6 only and it was 0.585 or 58.5% indicate a moderate internal consistency which was generally acceptable considering that it was only a 2-item measures. According to a small number of scale items would violate tau-equivalence and give a lower reliability coefficient. The overall reliability tests of the study questionnaires showed 0.735 or 73% indicating high internal consistency.

Data collection Process

a) After obtaining the administrative approval to conduct the

study and contacting the educational affairs department, the data

was collected two hours per day, two days per week for every

faculty. The available students in those hours were recruited.

b) The students’ written consents were obtained after

explaining the aim of the study and assuring the confidentiality and

anonymity, as well as their right to refuse and withdraw from the

study.

c) The students were given the questionnaires during their

presence in the lobby or the class between or after the lectures’

times.

d) The questionnaires needed approximately 10 - 20 minutes

to be filled up.

e) The researcher was the only person distributing and

responding to students’ inquiry.

f) The researcher reviewed each collected questionnaire to

assure its completeness and if there is any missing data.

g) The data was collected by the researcher over two months,

started from the beginning of February 2019 to the end of March

2019.

h) The collected data was kept in locked locker and it will be

destroyed after one year.

Data Analysis

Statistical Packages for Software Sciences (SPSS) version 21 has been used to perform all statistical analysis for this study SPSS Inc. [29]. Descriptive statistics has been presented as numbers, percentages and mean (SD) whenever appropriate. Inferential statistics has been used to analyse the relationship between variables. The relationship between both categorical variables (dependent variable vs independent variables) has been calculated using chi square test ( x^2 ), while the statistical association of two categorical variables (dependent) vs continuous variables (independent) has been calculated using independent t-test. Oneway Anova was used for three or more categorical variable vs continuous variable. Correlation procedures were also conducted using Spearman Rho correlation. Normality test were conducted using Shapiro Wilk Test. The significant of the results was categorized as follow; P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant and P-value ≤ 0.01 considered high statistically significant while P-value > 0.05 was considered non-significant.

RESULTS

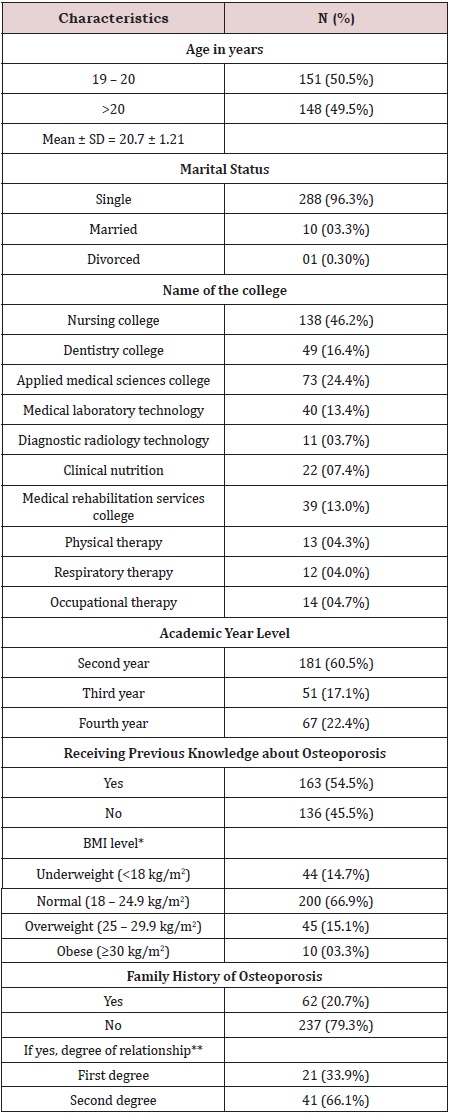

Two hundred ninety-nine female health- colleges students were recruited to evaluate their knowledge, beliefs and behaviours regarding Osteoporosis. The results of the current study were as follow: Regarding the characteristics of the study participants, Table 1 shows that, the mean age of the study participants was 20.7 (SD = 1.21) years. With regards to the level of BMI, 66.9% had normal BMI. Also, the table shows that, 96.3%of the study participants were single, 46.2% were enrolled in nursing college, 60.5% of the study participants were in their second academic year. In addition, 54.5% of the study participants had previously received knowledge about osteoporosis and 20.7% reported having a family member with osteoporosis (33.9% first degree relative; 66.1% second degree relative).

Table 2 describes study participants’ response to osteoporosis knowledge assessment tool (OKAT). Based on the results, 97.3% of the study participants knew that osteoporosis lead to an increased risk of bone fractures and 80.3% were aware that the majority of women by the age of 80 have osteoporosis. Moreover, 54.5% knew that an adequate amount of calcium intake can be achieved from two glasses of milk a day and 52.2% knew that having a higher peak bone mass at the end of childhood gives protection against the development of osteoporosis in later life. While only 18.4% were aware that not any type of physical activity is beneficial for osteoporosis and only 9.4% knew that osteoporosis (silent disease) causes no symptoms before fractures.

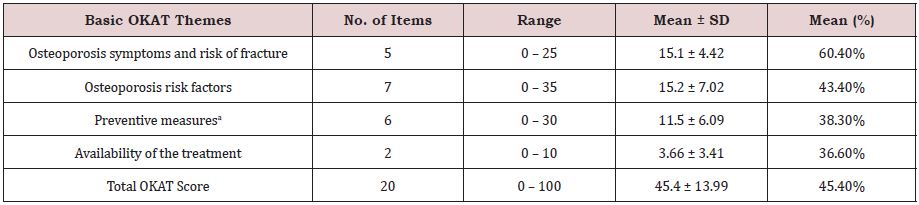

Regarding the four basic osteoporosis knowledge themes, it was found that, mean percent scores for osteoporosis symptoms and risk of facture was 60.4% which indicates a satisfactory level of awareness regarding osteoporosis symptoms and risk of fracture. While unsatisfactory level of awareness regarding osteoporosis risk factors, preventive measures and availability of the treatment were founded with mean percent scores 43.4%, 38.3% and 36.6% respectively. The overall mean percent score of OKAT questionnaire was 45.4% (Table 3).

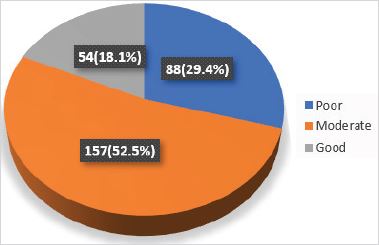

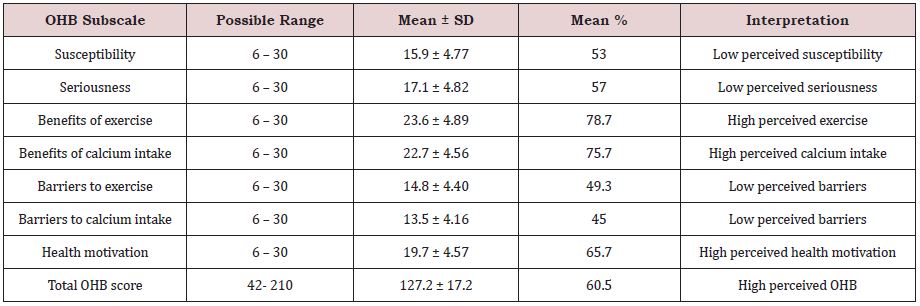

Figure 1 shows the level of study participants’ knowledge regarding osteoporosis. Based on study finding, it was found that, 52.5% of the study participants had a moderate level of knowledge regarding osteoporosis while 29.4% had poor level of knowledge and only 18.1% had good level of knowledge. With regards to osteoporosis health belief (OHB), it was found that, mean percent scores for perceived susceptibility and seriousness subscales were 53% and 57% respectively, which denoting low perceived susceptibility and seriousness regarding osteoporosis. Also, there were low perceived barriers for exercise and calcium intake with mean percent scores 49.3% and 45% respectively. While, the benefits of exercise and calcium intake in addition to health motivations revealed high perception with mean percent scores78.7 %, 75.7 % and 65.7 % respectively. Also, the total OHB scores indicated high perceived health beliefs regarding osteoporosis with mean percent 60.5 % (Table 4).

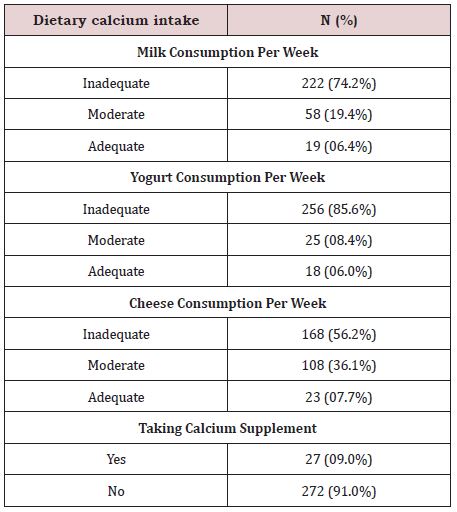

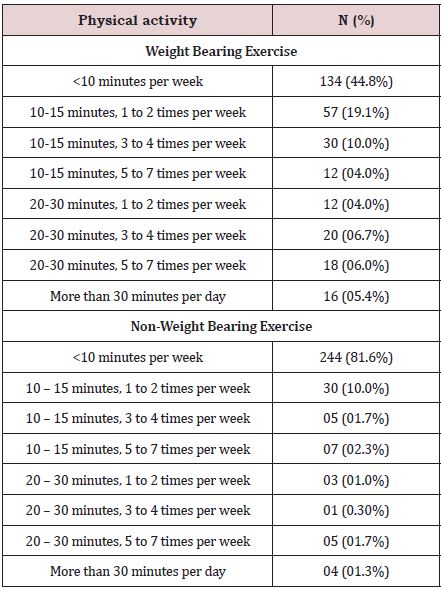

Table 5 presents the results of osteoporosis preventive behaviours related to dietary calcium intake among the study participants. Based on the results in this table, it was found that, 74.2% consumed inadequate amount of milk per week, 85.6 % consumed inadequate amount of yogurt per week and 56.2% consumed inadequate amount of cheese per week whereas only 9% were taking calcium supplements. Table 6 elaborates the assessment of osteoporosis preventive behaviours (OPBS) related to physical activity among study participants. It was found that, 44.8% were performing weight bearing exercise for less than 10 minutes per week while only 5.4% were performing vigorous weight bearing exercise for more than 30 minutes per day. On the other hand, 81.6% were exercising a non-weight bearing exercise for less than 10 minutes per week while only 1.3% were performing a vigorous non-weight bearing exercise for more than 30 minutes per day.

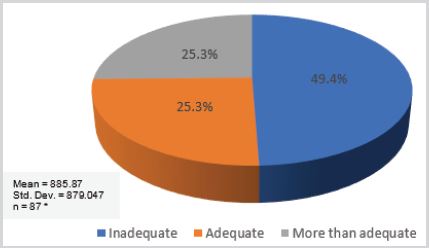

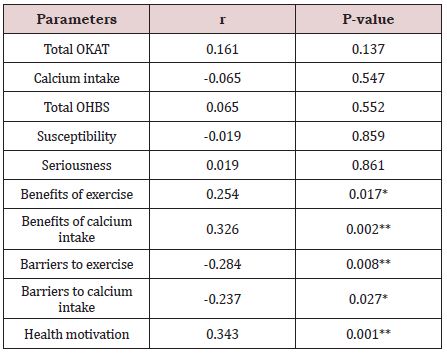

With regards to the level of physical activity among the study participants in accordance to MET minutes per week, it was observed from this figure that, the level of physical activity among 49.4 % of the study participants was inadequate, while, the level of physical activity among 25.3% was adequate and 25.3% were performing physical activity more than the adequate level. Also, it was found that, metabolic equivalent of task (MET) mean scores were 885.9 (SD = 879.05) (Figure 2). A Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was conducted to determine the correlations between participants’ knowledge, beliefs regarding osteoporosis and calcium intake with physical activity. The result in Table 7 indicates that, there were significant positive correlations were found between physical activity and benefits of exercise subscale mean scores (r=0.254, p=0.017), benefits of calcium intake subscale (r=0.326, p=0.002) and health motivation subscale (r=0.343, p=0.001). On the other hand, negative significant correlations had been detected between physical activity and both of barriers to exercise and calcium intake subscale (r=-0.284, p=0.008; r=-0.237, p=0.027) respectively.

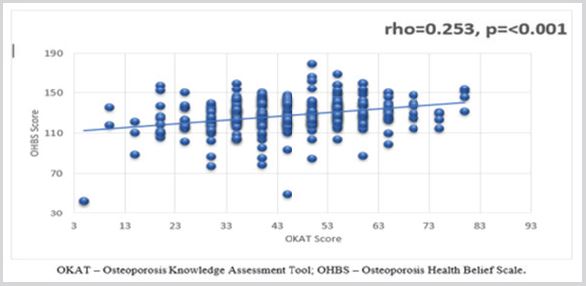

Statistical analysis using Spearman rho correlation was conducted to measure the correlations between knowledge, beliefs and physical activity with calcium intake. The result in this table shows that, there was no significant correlation has been observed. Spearman rho correlation conducted between the study participants’ osteoporosis preventing behaviour and their osteoporosis knowledge revealed that, there was no statistically significant correlation between them (rho=0.111, p=0.056). When finding the correlation between the study participants’ osteoporosis preventing behavior and their health belief, it was found that, there was no statistically significant correlation between them (rho=0.021, p=0.717). When correlating the study participants’ osteoporosis knowledge and their health beliefs, it was found that, there was highly significant positive correlation was determined between them (rho=0.253, p=<0.001) (Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

The present study was conducted to determine the knowledge, beliefs and behaviours regarding osteoporosis among female students in health colleges at King Abdulaziz University.

Interpretation of the results

Concerning study participants’ characteristics, the findings of the current study revealed that, more than half of the study participants had received previous information about osteoporosis through courses or something else which considered insufficient as they are health-college students. Because young women do not perceive themselves to be susceptible to osteoporosis, they are not concerned to get information regarding this disease. Also, it may be due to the lack of public awareness campaigns or unavailability of frequent courses about osteoporosis and its preventive measures to promote women’s health.

The current study finding is not concurrent with the study conducted in United Arab Emirates by Al-Hemyari et al. [30] to evaluate the knowledge, attitude and practice of university students towards osteoporosis and found that, 96% of their study participants had previous knowledge about osteoporosis.

Also, it was found that, one-fifth of the study participants reported having a family member affected with osteoporosis. This finding was almost the same with the finding of the study conducted by Akhtar et al. [31], who found that, 20% of their study participants had a positive family history of osteoporosis. While, it is not consistent with the findings of the study conducted by Almalki et al. [32] in Saudi Arabia to assess the knowledge on symptoms, risk factors, preventive measures and treatment regarding osteoporosis in healthy women of child bearing age in Fauji Foundation Hospital. And the study conducted by Mortada et al. [33] to assess the osteoporosis knowledge among 140 Medical Interns from nine Medical Schools in Saudi Arabia., which revealed a positive family history of osteoporosis reported by 36.7 % and 32.9% of the study participants respectively.

Also, the same is not consistent with the findings of the study conducted by Abdullah [34] to determine risk factors and awareness with preventive measures for osteoporosis among 225 nursing students in King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, KSA which found that, almost one third (32%) of the study participants have family history of osteoporosis. All of these results indicate high incidence of osteoporosis within the Saudi community which emphasise the importance of engagement in the osteoporosis preventive behaviours.

The assessment of the current study participants’ knowledge regarding osteoporosis revealed that, the mean percent scores of study participants’ knowledge regarding osteoporosis was less than fifty percent (9.8 out of 20). By comparison of this finding with the findings of other studies which used the same tool (OKAT) for measuring the knowledge about osteoporosis, Senosy [35] reported that, the mean scores about osteoporosis knowledge among 393 students from five randomly selected colleges of Beni- Suef University in Egypt was 11 out of 20.

Also, the current study finding was to some extent near the findings of Bilal et al. [20], who found that, the mean percent scores of osteoporosis knowledge among female medical school entrants was 33.2% and the result of the study conducted by Sayed-Hassan et al. [36], to determine the level of osteoporosis knowledge and beliefs among 359 nursing college students in Damascus, who stated that, the mean scores of the nursing students’ knowledge in their study was 7.9 out of 20.

In relation to the study participants’ level of knowledge, the current study revealed that, more than half of them had moderate level of knowledge regarding osteoporosis (40- 60%), less than one third of the study participants had poor level of knowledge (<40%), while only less than one-fifth of the study participants had good knowledge (>60%). This finding is consistent with the findings of De Silva (2014) who conducted a study among the female medical school entrants to determine the knowledge, beliefs and practices regarding osteoporosis among 186 young females entering medical schools in Sri Lanka and found that, 51.6% of the study participants had an average score on the knowledge about osteoporosis, and 40.8% had a poor score.

The same finding is almost similar to what is reported by Bilal et al. [20], who conducted a study to assess knowledge, attitudes and practices about osteoporosis among 400 female medical school entrants in Karachi, which revealed that 49.0% of the female medical school entrants had an average score of knowledge, 41.0% had a poor score while only 8.0% of the study participants had a good score. This may be due to the lack of focusing on osteoporosis in the faculties’ curriculum or they may deal with it as an unimportant topic.

In relation to the four basic themes regarding osteoporosis knowledge. The result of the study indicated that, there was a satisfactory level of knowledge regarding osteoporosis symptoms and risk of fracture. While, there was unsatisfactory level of knowledge regarding osteoporosis risk factors, preventive measures and availability of the treatment. These findings are close to what is found in the study conducted by Sayed-Hassan et al. [36] which conducted among female nursing school students in Damascus which found that, the mean percent scores of knowledge regarding osteoporosis symptoms and risk of fracture, osteoporosis risk factors, preventive factor and availability of the treatment were 50%, 32.8%, 45% and 25% respectively.

The osteoporosis health belief model contributes to understanding the preventive behaviours which are followed. The overall perceived osteoporosis health belief mean score in the current study is 127.2 ± 17.2 SD out of 210 with mean percent score 60.5%. Furthermore, among osteoporosis health belief subscales, it was found that there are high perceived benefits of exercise, high perceived benefits of calcium intake and high perceived health motivation.

These findings are consistent with the findings of the study conducted by Edmonds et al. [37] to examine the relationships between osteoporosis knowledge, beliefs and calcium intake among 792 college students at mid-western regional university in the US; who reported presence of high perceptions to benefits of exercise and calcium intake among college students. The high perceived benefits of exercise and calcium intake could be due to the great emphasis on benefits of exercise and benefits of calcium intake via health programs and advertisements in the mass media and internet. While, the high perceived health motivation may be because the study participants are of health colleges so, they get health information through their courses and are motivated to follow the health recommendations to keep healthy.

In contrast, the current study revealed presence of low perceived susceptibility, low perceived seriousness, low perceived barriers to exercise and low perceived barrier to calcium intake. These findings related to low perceived susceptibility, low perceived barriers to exercise and low perceived barrier to calcium intake are consistent with the findings of the study conducted by Nguyen [38] who reported low to moderate perception of seriousness among their studies participants. From the researcher’s point of view, the possible explanation for this finding is that, the study participants do not see themselves vulnerable to osteoporosis as they are still young and they belief that osteoporosis is an older adults’ disease. Also, they beliefs that the disease is not a serious or life-threatening disease compared to other diseases, such as heart diseases, HIV, cancer and diabetes pose more serious health consequences than osteoporosis Khan et al. [39]. Even the positive view to calcium intake and physical activity and low barrier to calcium intake and physical exercise, it still not translated effectively to act by adequately practicing a preventive behaviour toward osteoporosis. The lower perceptions of both susceptibility and seriousness to osteoporosis had more influence on them than the other good perceptions (low perceptions to the barrier of calcium intake and physical activity and high perceptions to the benefits to the both preventive behaviours).

The adherence to dietary calcium intake is vital to the long-term improvement of bone health. As this is one of the most important factors to osteoporosis preventive behaviour, an assessment of dietary calcium intakes is needed in order to come up with a better approach NIH [40]. The current study result indicated that, most of the study participants don’t consume adequate amounts of milk or yogurt per week. While, in relation to cheese consumption per week, it was found that few numbers of them consume adequate amount and more than one third consume moderate amount of cheese. Also, the minority receive calcium supplement regularly.

These findings are congruent with study done by Edmonds et al. [37] who found that the consumptions of milk, yogurt, cheese per week appears inadequate amounts by 62.5 %, 94 % and 56% of their study participants respectively, whereas only 10.7 % were taking calcium supplements. These could be due to their preference as they may prefer the fast food over this food also the availability of the junk food, sweets and coffee everywhere in the university which leads to increase the appetite for it.

Concerning the physical activities, this study revealed that, less than half of the study participants engaged in a weight bearing exercise for only less than 10 minutes per week, a few number were performing weight bearing exercise for more than 30 minutes per day and the majority of them engaged in a non-weight bearing exercise for only less than 10 minutes per week while very few number were performing a non-weight bearing exercise for more than 30 minutes per day.

These results denoting inadequate level of physical activity and not meeting the WHO recommendation regarding physical activity (150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity/ week or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity physical activity/ week) WHO [41]. These findings are not congruent with the finding of the study done by Edmonds et al. [37] who found that 13.3 % of their study participants engaged in a weight bearing exercise for only less than 10 minutes per week while 15.7% were performing weight bearing exercise for more than 30 minutes per day and 57.7% of the study participants engaged in a non-weight bearing exercise for only less than 10 minutes per week while only 3 % were performing a non-weight bearing exercise for more than 30 minutes per day. Unfortunately, this is a challenging reality to public health in Saudi Arabia and highlights the important of increasing public awareness regarding physical activity.

Regarding physical activity based on metabolic equivalent of task (MET) / minutes per week, the study revealed that, more than half of the study participants who perform physical activity (n= 87out of 299) perform adequate or more than adequate level of physical activity and meet the recommended level of physical activity by WHO in 2015 (600-1200 MET minutes per week). Moreover, the mean score of MET/ minutes per week for all the study participants who perform physical activity was 885.87 Unlike, Edmonds et al. [37] founds that, the mean of the MET minutes per week in their study was 1212.46. The findings of this study may be due to the sedentary lifestyle which most of the youth live as a result of availability of the internet and smart devices which occupy their life or may be because the study participants were selected from practical colleges where they are occupied by their study and frequent assignments.

Spearman correlation was used for data analysis to find the correlations between study participants’ knowledge regarding osteoporosis and their practicing for physical activities. The analysis revealed that, there was no correlation between them; this finding may be due to the fact that knowledge about the disease only is not enough for practicing physical activities by the study participant; and they need motivation and encouragement also to practice it.

Studying the correlations between study participants’ health beliefs regarding osteoporosis and physical activities revealed presence of positive correlations between physical activity and perceived benefits of exercise, perceived benefits of calcium intakes and health motivation while, there was a negative correlation between physical activity and barrier to exercise and barrier to calcium intakes. Almost the same results were founded by the study conducted by Gammag and Klentrou who were investigating whether the expanded Health Belief Model could predict calcium intake and physical activity in 510 adolescent girls from 8 different schools; and found that, physical activity was positively related to health motivation and negatively associated with calcium and exercise barriers.

These results indicate that, the higher the perception of exercise and calcium intake benefits and the higher health motivation in addition to the lower perception to the barrier to exercise, the higher the level of the study participants’ engagement in physical activity to reduce the risk of osteoporosis.

Regarding the correlation between study participants’ knowledge and health beliefs about osteoporosis, it was found that, there was positive correlation between the participants’ knowledge and their health belief. This finding is contradiction with the finding of the study done by Ziccardi et al. [42]; Sedlak et al. [43]; kasper, et al. [44] who found that, there are no relation between the study participants’ knowledge and health beliefs regarding osteoporosis. The current study finding may highlight the positive effect of the participants’ knowledge on their beliefs, which in turn will increase the level of study participants’ engagements in osteoporosis preventive behaviours.

Studying the correlation between the study participants’ osteoporosis preventing behavior and their health belief revealed absence of correlation between them. This finding is incongruent with the study done by Aree-Ue [45] to examine the differences in osteoporosis knowledge, health beliefs, and preventive behaviours between younger and older Thai women; and found that, health beliefs about osteoporosis were significantly related to osteoporosis preventive behaviour for the older group, but not for the younger group [46].

LIMITATION

This study had some limitations to be considered: The study was accessed into four university health programs only (nursing, dentistry, applied medical sciences, medical rehabilitation services), while faculty of medicine and pharmacy were not included in the study sample, because their recruitments were very difficult during pilot study as they were very busy most of the time. Therefore, this may not represent other health sciences students’ knowledge, beliefs and behaviours.

The convenience sampling methods used limits the generalization of the study results. Also, the sample doses not fully represent all university students across Saudi Arabia, since the study participants were drawn from one university in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Therefore, random sampling method is suggested for future studies.

CONCLUSION

Based on the study results, the study questions were answered. The current study concluded the following: More than half of the studied female health science students had moderate level of knowledge toward osteoporosis. There was unsatisfactory level of knowledge regarding osteoporosis risk factors, preventive measures and availability of the treatment. The beliefs of perceived susceptibility and seriousness of osteoporosis were low, which may explain the concluded inadequate level of practicing osteoporosis preventive behaviours by the study participants (calcium intake and physical exercise). Also, the level of physical activity was affected positively by the perceived benefits of exercise, perceived benefits of calcium intake and perceived health motivation. In addition, the level of physical activity was affected negatively by the both perceived barriers to exercise and perceived barriers to calcium intake, this means that, the lower the perception of barriers to exercise and calcium intake, the higher practicing physical activity.

Furthermore, there was a positive relation between the female health science students’ knowledge regarding osteoporosis and their health beliefs, this denoting that, the higher knowledge of osteoporosis among those students had influenced their health beliefs positively towards osteoporosis.

RECOMMENDATIONS

According to the study result, the researcher recommended to provide health education and prevention programs about osteoporosis targeted university students or even to include it in the curriculum to raise their awareness toward osteoporosis and to ensure the accuracy of information provided. Also, to narrow the gap between knowledge and practices in order to reduce the burden of the disease on the community.

REFERENCES

- McLendon AN, Woodis CB (2014) A review of osteoporosis management in younger premenopausal women. Women’s Health 13 (73): 5977.

- World Health Organization (WHO) Scientific Group (2003) The burden of musculoskeletal conditions at the start of the new millennium. World Health Organization technical report series.

- Chen X, Wang Z, Duan N, Zhu G, Schwarz EM (2018) Osteoblast-osteoclast interactions. Connect Tissue Res 59(2): 99-107.

- Matsuoka K, Park K, Ito M, Ikeda K, Takeshita S (2014) Osteoclast-Derived Complement Component 3a Stimulates Osteoblast Differentiation. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 29(7): 1522-1530.

- Weaver CM, Gordon CM, Janz KF, Kalkwarf HJ, Lappe JM, et al, (2016) The National Osteoporosis Foundation’s position statement on peak bone mass development and lifestyle factors: a systematic review and implementation recommendations. Osteoporos Int 27(4): 1281-1386.

- Berger C, Goltzman D, Langsetmo L, Joseph L, Jackson S, et al. (2010) Peak bone mass from longitudinal data: Implications for the prevalence, pathophysiology, and diagnosis of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 25(9): 1948-1957.

- Langdahl B, Ferrari S, Dempster DW (2016) Bone modeling and remodeling: potential as therapeutic targets for the treatment of osteoporosis. Therapeutic advances in musculoskeletal disease, 8(6): 225-235.

- Rodzik EB (2008). Osteoporosis education in college-age women.

- Zarshenas L, Keshavarz T, Momennasab M, Zarifsanaiey N (2017) Interactive multimedia training in osteoporosis prevention of female high school students: an interventional study. Acta Medica Iranica, 55(8): 514-520.

- Endicott RD (2013) Knowledge, health beliefs, and self-efficacy regarding osteoporosis in perimenopausal women. J Osteoporos 2013: 1-6.

- Sadat-Ali M, Al-Habdan IM, Al-Turki HA, Azam M (2012) An epidemiological analysis of the incidence of osteoporosis and osteoporosis-related fractures among the Saudi Arabian population. Ann Saudi Med 32(6): 637-641.

- DeRuiter-Willems L (2018) Comparison of osteoporosis knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and behavior among college students of various racial/ ethnic groups.

- Krmoyan V (2016) Osteoporosis knowledge, beliefs, and practice among the general population in Yerevan and Gyumri.

- Gammage KL, Klentrou P (2011) Predicting osteoporosis prevention behaviors: health beliefs and knowledge. Am J Health Behav 35(3): 371- 382.

- Gammage KL, Gasparotto J, Mack DE, Klentrou P (2012) Gender differences in osteoporosis health beliefs and knowledge and their relation to vigorous physical activity in university students. J Am Coll Health 60(1): 58-64.

- US Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) (2004) Bone health and osteoporosis: a report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, US.

- Enteshari-Moghaddam A, Zakeri A, Atalu A, Abbasi V (2019) Knowledge of medical university students over osteoporosis. Archives of Advances in Bioscience 10(2): 43-50.

- National Institutes of Health (2018) Osteoporosis: Peak bone mass in women.

- Ramli N, Rahman NAA, Haque M (2018) Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding osteoporosis among allied health sciences students in a public university in Malaysia. Erciyes Medical Journal/Erciyes Tip Dergisi 40(4): 45-68.

- Bilal M, Haseeb A, Merchant AZ, Rehman A, Arshad MH, et al. (2017) Knowledge, beliefs and practices regarding osteoporosis among female medical school entrants in Pakistan. Asia Pac Fam Med 16(1): 6.

- De Silva RE, Haniffa MR, Gunathillaka KD, Atukorala I, Fernando ED, et al. (2014) A descriptive study of knowledge, beliefs and practices regarding osteoporosis among female medical school entrants in Sri Lanka. Asia Pac Fam Med 13(1): 15.

- Raosoft, Inc (2004) Sample size calculator.

- Winzenberg TM, Oldenburg B, Frendin S, Jones G (2003) The design of a valid and reliable questionnaire to measure osteoporosis knowledge in women: The Osteoporosis Knowledge Assessment Tool (OKAT). BMC musculoskeletal disorders 4: 17.

- Kim KK, Horan ML, Gendler P, Patel MK (1991) Development and evaluation of the osteoporosis health belief scale. Research in Nursing & Health 14(2): 155-163.

- Doheny M, Sedlak C (1995) Osteoporosis preventing behaviors survey.

- Edmonds ET (2009) Osteoporosis knowledge, beliefs, and behaviours of college students. (Doctoral dissertation, University of Alabama, Alabama).

- Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, Meckes N, Bassett DRJ, et al. (2011) 2011 Compendium of Physical Activities: A Second Update of Codes and MET Values. Med Sci Sports Exerc 43(8): 1575-1581.

- Howley ET (2000) You asked for it question authority. ACSM’s Health & Fitness Journal 5(2): 5.

- SPSS Inc (2012) Statistical Package for the Social Sciences.

- Al-Hemyari,S, Jairoun AA, Jairoun MA, Metwali Z, Maymoun N (2018) Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) of osteoporosis and its predictors among university students: cross sectional study, UAE. Journal of Advanced Pharmacy Education & Research 8(3): 43-48.

- Akhtar A, Shahid A, Jamal AR, Naveed MA, Aziz Z, et al. (2016) Knowledge about osteoporosis in women of childbearing age (15-49 years) attending fauji foundation hospital Rawalpindi. Pak Armed Forces Med J 66(4); 558-563.

- Almalki N, Algahtany F, Alswat K (2016) Osteoporosis knowledge assessment among medical interns. American Journal of Research Communication 4(1): 1-14.

- Mortada E, El Seifi O, Abdo N (2020) Knowledge, health beliefs and osteoporosis preventive behaviour among women of reproductive age in Egypt. Malaysian Journal of Medicine and Health Sciences 16: 9-16.

- Abdullah WH (2017) Risk factors and preventive measures awareness among nursing students regarding osteoporosis. IOSR Journal of Nursing and Health Science 6(2): 7-21.

- Senosy SA, Elareed H (2017) Impact of educational intervention on osteoporosis knowledge among university students in Beni-Suef, Egypt. Journal of Public Health 26(2): 219-224.

- Sayed-Hassan R, Bashour H, Koudsi A (2013) Osteoporosis knowledge and attitudes: a cross-sectional study among female nursing school students in Damascus. Archives of osteoporosis 8(1): 149.

- Edmonds E, Turner LW, Usdan SL (2012) Osteoporosis knowledge, beliefs, and calcium intake of college students: Utilization of the health belief model. Open Journal of Preventive Medicine 2(1): 27.

- Nguyen VH (2015) Osteoporosis-preventive behaviors and their promotion for young men. Bonekey Rep 4: 729.

- Khan YH, Sarriff A, Khan AH, Mallhi TH (2014) Knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) survey of osteoporosis among students of a tertiary institution in Malaysia. Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research 13(1): 155-162.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH) (2018). Osteoporosis Overview.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2015) Physical activity and adults.

- Ziccardi SL, Sedlak CA, Doheny MO (2004) Knowledge and health beliefs of osteoporosis in college nursing students. Orthopaedic Nursing 23(2): 128-133.

- Sedlak CA, Doheny MO, Jones SL (2000) Osteoporosis education programs: Changing knowledge and behaviors. Public Health Nursing 17(5): 398-402.

- Kasper MJ, Peterson MGE, Allegrante JP, Galsworthy TD, Gutin B (1994) Knowledge, beliefs, and behaviors among college Women concerning the prevention of Osteoporosis. Arch Fam Med 3(8): 696-702.

- Aree-Ue S, Petlamul M (2013) Osteoporosis knowledge, health beliefs, and preventive behavior: a comparison between younger and older women living in a rural area. Health Care Women Int 34(12): 1051-1066.

- International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) (2019) IOF Compendium of Osteoporosis. (2nd edn).

Article Type

Research Article

Publication history

Received date: July 28, 2020

Published date: August 17, 2020

Address for correspondence

Ensherah Saeed Althobiti, RN, BSN, MSN, Medical Surgical Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, King AbdulAziz University, Saudi Arabia

Copyright

©2020 Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science, All rights reserved. No part of this content may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means as per the standard guidelines of fair use. Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

How to cite this article

Ensherah Saeed A, Elham Abdullah Al N, Asma Hamdi M. Knowledge, Beliefs and Preventive Behaviours Regarding Osteoporosis Among Female Health Colleges’ Students at King Abdulaziz University. 2020 - 2(4) OAJBS.ID.000207.

Figure 1: Level of Knowledge Regarding Osteoporosis among the Study Participants.

Figure 2: Level of Physical Activity among the Study Participants According to Metabolic Equivalent of Task (MET)

Minutes per Week (n=87).

*n= 87: number of students who actively participated in physical activity in the last seven days.

Figure 3: Spearman rho correlation between the study participants’ osteoporosis knowledge and their health belief.

Table 1: Characteristics of Study Participants (n=299).

*Body Mass Index (BMI) = wight/((hight )^2)

**Only participants who had family history of osteoporosis

were included in the analysis.

Table 2: Study Participants’ Knowledge Regarding Osteoporosis (n=299).

Table 3: Means and standard deviation of the study participants’ knowledge themes scores regarding osteoporosis (n=299).

Table 4: Means and standard deviation of the osteoporosis health beliefs scores (OHB) (n=299).

Table 5: Assessment of osteoporosis preventive behaviours among study participants related to dietary calcium intake(n=299).

Table 6: Assessment of osteoporosis preventive behaviours among study participants related to physical activity (n=299).

Table 7: Correlation between, knowledge, beliefs and calcium intake with physical activity (Sqrt MET/MIN) (n=299).