Hepatitis C Virus Infection and Risk Factors Among Immigrants Asymptomatic Blood Donors in Kuwait: A Case-Control Study

ABSTRACT

Objectives: To evaluate travel history and other known risk factors for HCV infection among resident immigrants volunteer

asymptomatic blood donors in Kuwait Central Blood Bank.

Subjects and Methods: In this case-control study, case defined as an expatriate blood donor tested HCV seropositive in Kuwait

during last 5 years. Control defined as an immigrant’s asymptomatic blood donor, tested seronegative for HCV, HBV and HIV

infections during the same period. A structured questionnaire used in an interview to collect the data both from cases and controls.

Results: The study confirmed the association of HCV with demographic, behavioral and medically related risk factors as surgical

intervention, extramarital sexual contact and family history of HCV infection. Also identified that history of travel to home country

namely frequency of travel to home country and average length of stay in home country during visit could be major risk factors for

HCV infection discovered in Kuwait.

Conclusion: These findings require comprehensive review and update of residency medical requirements in State of Kuwait and

other gulf countries. And full implementation of comprehensive infection control guidelines during surgical and dental procedures

to reduce the risk of HCV infection.

KEYWORDS

Hepatitis C; Blood Donors; Risk Factors; GCC; Arab

ABBREVATIONS

HCV: Hepatitis C Virus; DAAs: Direct Acting Antivirals; WHO: World Health Organization; EMR: Eastern Mediterranean Region; RT-PCR: Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction; NAT: Nucleic Amplification Testing; GCC: Gulf Cooperation Council; PHLs: Public Health Laboratories; SPSS: Statistical Package for Social Sciences; Cis: Confidence Intervals

HIGHLIGHTS

Resident immigrant’s visits of their home countries with Hepatitis C burden may acquire infection, posing a major public health concern.

Case-control study: to evaluate travel history and other risk factors for HCV infection among immigrant’s asymptomatic blood donors. Results confirmed association of HCV with surgical intervention, extramarital sexual contact, family history of HCV, and history of travel to home country.

INTRODUCTION

Infection with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) can result in both acute and chronic hepatitis. The acute process is most often asymptomatic and if symptoms are present, they usually abate within a few weeks [1]. Acute infection rarely causes hepatic failure. Up to 85% of the HCV infected patients develop chronicity that may lead to cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma. Enormous economic losses are associated with chronicity of HCV infection and disruption of social life both for patients and caregivers at homes [2,3]. The effective vaccine against HCV infection so far is not available [4]. Several anti-HCV drugs known as direct acting antivirals (DAAs) are available since 2014 [5] can cure more than 95% of persons with hepatitis C infection, thereby reducing the risk of death from cirrhosis and liver cancer, but access to diagnosis and treatment is low [5,6]. Globally, an estimated 58 million people have chronic hepatitis C virus infection, with about 1.5 million new infections occurring per year. There are an estimated 3.2 million adolescents and children with chronic hepatitis C infection. World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that in 2019, approximately 290 000 people died from hepatitis C, mostly from cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (primary liver cancer).

There is a substantial variation in prevalence and epidemiology of HCV among the countries of WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR) [7,8]. It is estimated that 0.8 million people are infected with HCV annually in countries of WHO EMR with HCV prevalence ranging from 1% -4.6% [4], with much higher levels in Egypt (14.7%) [7] and Pakistan (4.8%) [3]. Overall, an estimated 17 million people in the region suffer from chronic HCV infection [4]. Antiviral medicines pan-genotypic direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) for all adults, adolescents, and children down to 3 years of age with chronic hepatitis C infection usually 12 to 24 weeks can cure more than 95% of persons with hepatitis C infection, but access to diagnosis and treatment is low. Pan-genotypic DAAs remain expensive in many high- and upper-middle-income countries. There is currently no effective vaccine against hepatitis C.

HCV is transmitted through exposure to infectious blood. This may happen through transfusions of HCV-infected blood and blood products, contaminated injections during medical procedures, and sharing of needles and syringes among injecting drug users. Sexual or interfamilial transmission is also possible, but relatively is uncommon [9]. The main risk factor for acquiring HCV infection before the routine anti-HCV screening of blood donors was blood transfusion. Now the relatively high proportion of non-transfused hepatitis C cases suggests that transfusion is not the predominant route of transmission of HCV. Nowadays, intravenous drug abuse is the major risk factor for HCV infection [8]. The risk of HCV transmission through blood transfusion has been decreased dramatically by improved screening measures for blood donors [10-12]. Use of reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in healthy volunteer blood donors has also contributed to the decrease in rates of HCV infections. For example, HCV prevalence decreased significantly since nucleic acid amplification testing (NAT) introduction in USA [13]. Currently the level of post-transfusion hepatitis C is negligible in developed countries. However, transfusion of blood and blood products from improperly screened blood donors remains a source of HCV transmission in many developing countries [11].

In Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, a wide variation in HCV sero-prevalence among the asymptomatic blood donors has been reported ranging from 3.2% to 4.5% [14,15]. In Kuwait the prevalence of HCV infection among first-time blood donors is 0.8% and 5.4% among Kuwaiti and non- Kuwaiti Arab donors, respectively [10]. Kuwait succeeded in keeping the HCV prevalence and incidence very low mainly through pre-employment screening, screening of blood donation, premarital screening, prenatal and screening of expatriates before issuing residency [16,17]. Resident expatriates during frequent visits of their home countries with high HCV burden may acquire HCV infection in turn pose risk of transmission within Kuwait. Thus, such HCV infected resident expatriates in Kuwait poses a major public health concern. Therefore, main question was could immigrants’ travel history to their home countries with varying length of stay and exposures to different hazardous risk factors predispose them to HCV infection? Especially, with limited affordability and accessibility of DAAs, particularly in migrants with lower-income Therefore, this casecontrol study is proposed to identify the risk factors associated with HCV infection among resident expatriate volunteer asymptomatic blood donors in Kuwait.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study Population and Study Design

A case-control study to evaluate the potential risk factors for HCV seropositivity among immigrant’s asymptomatic blood donors conducted in Kuwait. The Central Blood Bank (KCBB) accepts apparently healthy blood donors. The donated blood sack screened for HCV, HBV and HIV by doing the Chemo-luminescent assay and the Nucleic Amplification test (NAT) in parallel in 2 different labs at KCBB. Any sero-positivity is confirmed by repeating NAT in Virology Laboratory, Public Health Laboratories (PHLs)-MOH.

Case Definition, Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria and Selection

An immigrant’s blood donor tested positive for HCV by Chemo-luminescent assay/ NAT and confirmed by NAT at Virology Laboratory, PHLs, MOH, at KCBB during last 5 years and willing to participate in the study. Expatriate, who would be sick, untraceable on phone call or moved out of Kuwait will be excluded. A list all HCV seropositive cases identified by KCBB and confirmed at PHLs during this period obtained from Communicable Diseases Control Unit (CDCU) Public Health Department used for case selection.

Control Definition, Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria and Selection

immigrants asymptomatic blood donor, HCV, HBV and HIV antibodies tested negative during last 5 years. Controls were frequency matched with cases by gender, month and year of donation. Donors HBV and HIV seropositive, sick, untraceable on phone call or moved out of Kuwait were excluded. A list frame of immigrants’ blood donors tested HCV seronegative during the same period obtained from KCBB used to select controls.

Sample Size

In this case-control study, all cases and controls were nonnational residents of State of Kuwait we found 76 HCV infection cases and randomly selected 162 controls matched with cases by gender, month and year of donation (1:2 ratio) to provide 80% power to estimate an odds ratio of 2.5 relating with outcome the risk factors having prevalence of 0.2 in controls. This assumes a level of significance of 5%.

Data Collection

Consenting cases and controls were interviewed using a structured questionnaire to collect the data regarding demographic, socioeconomic characteristics and various potential risk factors including parenteral exposures to blood or blood products, travel history, and contact history with a case of hepatitis C.

Covariate

All covariate data were collected at baseline including gender, age, nationality, religion, education, monthly income. Frequency of travel to home country categorized into once or more than once. Average length of stay-at-home country categorized into <1 month, 1-3 months or 4-6 months. All other factors were categorized into Yes or No including history of jaundice, surgery, dental care, blood transfusion, incidental needle brick, multiuse needles, shaving with public barber, share toothbrush, tattoo, handling blood or blood products, intravenous/ intramuscular drug usage, extramarital relationship, family member had history of HCV or jaundice or died from hepatitis or live diseases.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 26) used to analyze the data. Descriptive statistics demographic variables and potential risk factors computed for both cases and controls. To assess univariate associations between HCV seropositivity and hypothesized risk factors, Chi-squares and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values computed to determine whether there is a significant difference between categorical variables and HCV seropositivity status. Odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using conditional logistic regression. The variables related (p ≤ 0.25) to case-control status in univariate analyses were considered for inclusion in multivariate logistic regression model. And multivariable models were adjusted for average length stay in home country, surgery, dental care, ever had jaundice, extramarital relationship, family member had history of HCV, age, education level, frequency of travel to home country, incidental needle brick, intravenous or intramuscular drugs. In final multivariate logistic regression model variables independently related (p < 0.05) to the case-control were retained.

RESULTS

Description of Study Population

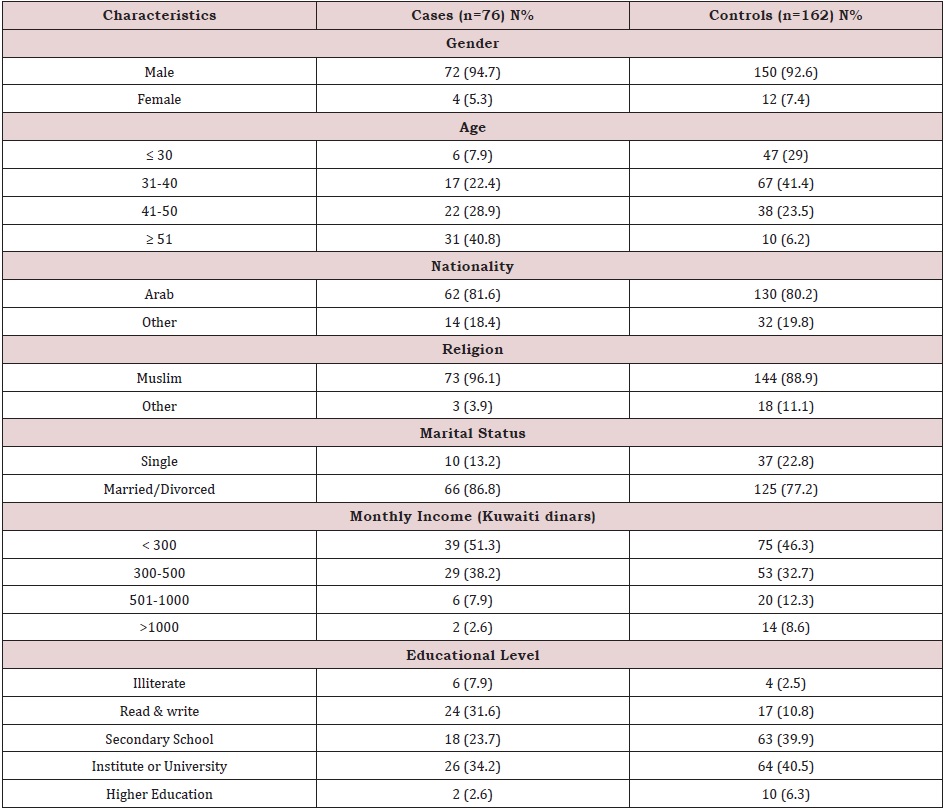

Socio-demographic characteristics of cases and controls enrolled to assess risk factors associated with HCV infection among immigrant’s blood donors in Kuwait are shown in (Table 1). A total of 94.7% of cases and 92.9% of controls were male. Most of participants were Arab in nationality, mainly Egyptians, (81.6% for cases and 80.2% for controls). The remaining were other nationalities mainly from Pakistan. Majority of participants were Muslims in religion (96.1% and 88.9% for cases and controls respectively). Only 13.2% of cases and 22.8% of controls were single. More than half of cases were having low monthly income less than 300 KD and 36.8% of cases and 46.8% of controls have completed 12 years or more of education.

Univariate Analysis

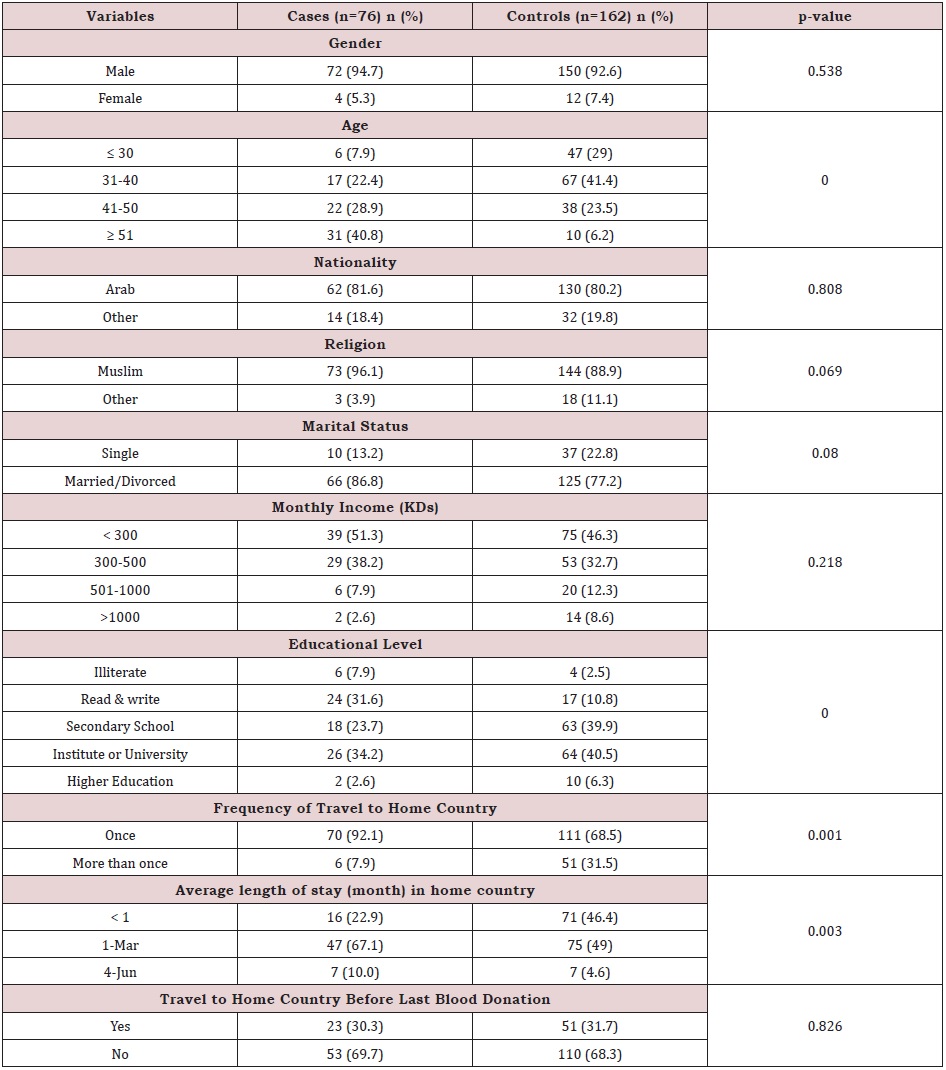

(Table 2) summarizes demographic, behavioral and medically related risk factors for HCV infection among blood donors. Age found to be positively associated with HCV infection. Level of education as expected is inversely associated with HCV infection. Among behavioral and medically related risk factors we found that ever had jaundice, surgery, dental care, blood transfusion, incident needle brick, intravenous or intramuscular drug use or family member had jaundice all were significantly associated with HCV infection. Frequency travel to home country and average length of stay in month in home country were also significant risk factors associated with HCV infection among cases more than controls.

Multivariable Logistic Regression Model

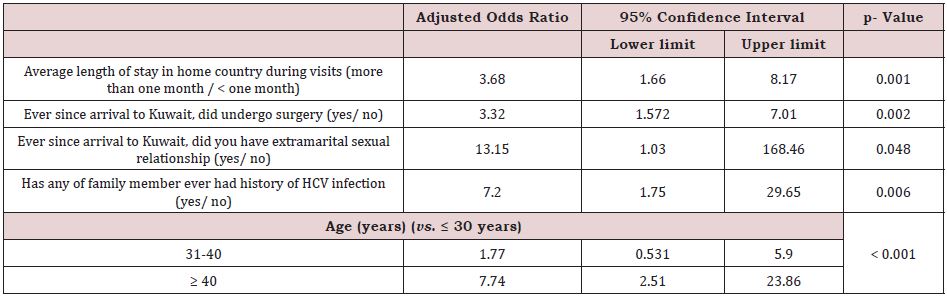

Multivariable logistic regression revealed that the average length of stay in home country during visits for more than one month over less than one month is positively associated with HCV infection (adjusted OR 3.68, p value 0.001). Cases were more likely to be reported among ever had surgery than controls (adjusted OR 3.32, p value 0.002). Family member of HCV was also associated with HCV seropositivity as cases more likely to have family member affected with hepatitis C (adjusted OR 7.2, p-value 0.006). More cases than controls also had extramarital sexual relationship (adjusted OR 7.2, p-value 0.04). Finally, age found to be associated with HCV infection among asymptomatic blood donors since more cases than controls were found in the older age groups than in the age group less than 30 years old (adjusted OR 1.77 and 7.77 respectively, p-value < 0.001); (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In this study we identified the association of HCV with known risk factors as surgical intervention, extramarital sexual contact and family history of HCV infection as in previous studies [18- 24]. The association of HCV with history of surgical intervention for any reason, calls for strengthening patient safety at health care facilities that needs the full implementation of comprehensive infection control guidelines [25]. Age was independent predictor of HCV infection in multivariable analysis as it was positively related to HCV infection [26-28] most probably related to unsafe medical practice for example the reuse or inadequate sterilization of medical equipment, especially syringes and needles in healthcare settings [29,30].

In univariate analysis education level, ever had jaundice, dental care, blood transfusion or incidental needle brick were also risk factors for HCV infection, but they lost their significance in multivariable analysis indicating that they could be somewhat dependent on other factors. The association of HCV and history of travel to home country as frequency of travel to home country as well as average length of stay in home country during visit indicate that getting infected while visiting home country could be a major source of HCV infection discovered in Kuwait, similar findings as previous studies [26]. Although all Gulf countries have mandated HCV screening prior to obtaining residency permits, migrants who test positive for HCV antibody are not necessarily deported. Moreover, those who became residents before the introduction of mandatory screening in the mid 1990s are usually allowed continuous residency even if found to be HCV antibody positive. Exposure to the infection has probably occurred in the countries of origin and not in the host countries. This pattern has also been observed by Perumal swami in a recent study conducted in New York City, they observed an HCV prevalence of 15.6% among Egyptian-born persons living in New York and a strong association between HCV exposure and the number of years resident in Egypt [31]. These findings require comprehensive review and update of residency medical requirements in State of Kuwait and other gulf countries.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The study confirmed the association of HCV with demographic, behavioral and medically related risk factors as surgical intervention, extramarital sexual contact and family history of HCV infection. Also identified that history of travel to home country namely frequency of travel to home country and average length of stay in home country during visit could be major risk factors for HCV infection discovered in Kuwait. These findings require comprehensive review and update of residency medical requirements in State of Kuwait for example re-examine those staying in their home country for more than 2 months during their visit.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

Usage of donor database as well as database of reported infectious diseases and confirmation of positive cases in public health laboratories. However, we couldn’t draw inferences about causality based on observed association from this case control study design. Or study might have encountered recall bias about the accurate history of past exposure like dental care, needle brick in home country or in Kuwait. Sexual behavior is culturally sensitive issue; it was difficult to extract detailed sexual behavior although we had significance association with extramarital sexual contact. Likewise, usage of IV drugs is considered as a crime and unaccepted socially so we couldn’t appraise it as risk factor in the study population. It was conducted on blood donors in general, thus it could not differentiate first time donor from a usual blood donor.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors gratefully thank Kuwait Central Blood Bank especially “RIP Dr. Nabeel Sanad” and Public Health Department for their cooperation and facilities during data collection.

STATEMENT OF ETHICS

Ethical clearance obtained from Ministry of Health Ethics Review Committee. Written consent for an interview was taken from each case and control and assured about the confidentiality of his information.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

None of the authors had any personal or financial potential conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Hoshida Y, Fuchs BC, Bardeesy N, Baumert FT, Chung TR, et al. (2014) Pathogenesis and prevention of hepatitis C virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 61(1): S79-S90.

- Khan UR, Janjua ZN, Akhtar S, Hatcher J (2008) Case-control study of risk factors associated with hepatitis C virus infection among pregnant women in hospitals of Karachi-Pakistan. Trop med Int Health 13(6): 754-761.

- Ahmad K (2004) Pakistan: A cirrhotic state? Lancet 364(9448): 1843- 1844.

- Chen DS, Locarnini S, Wait S, Bae SH, Chen PJ, et al. (2013) Report from a viral hepatitis policy forum on implementing the WHO framework for global action on viral hepatitis in north Asia. J Hepatol 59(5): 1073-1080.

- Rosenthal ES, Graham CS (2016) Price and affordability of direct-acting antiviral regimens for hepatitis C virus in the United States. Infectious Agents and Cancer 11: 24.

- (2019) WHO: Hepatitis C Fact Sheet.

- Mohamoud YA, Mumtaz RG, Riome S, Miller D, Abu-Raddad JL, et al. (2013) The epidemiology of hepatitis C virus in Egypt: a systematic review and data synthesis. BMC infect dis 13: 288.

- Fallahian F, Najafi A (2011) Epidemiology of hepatitis C in the Middle East. Saudi journal of kidney diseases and transplantation: an official publication of the Saudi Center for Organ Transplantation. Saudi Arabia 22(1): 1-9.

- Murphy EL, Bryzman SM, Glynn SA, Ameti DI, Thomson RA, et al. (2000) Risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection in United States blood donors. NHLBI retrovirus epidemiology donor study (REDS). Hepatology 31(3): 756-762.

- Ameen R, Sanad N, Al-Shemmari A, Siddique I, Chowdhury IR, et al (2005) Prevalence of viral markers among first-time Arab blood donors in Kuwait. Transfusion 45(12): 1973-1980.

- Khattak MN, Akhtar S Roshan TM (2008) Factors influencing hepatitis C virus sero-prevalence among blood donors in northwest Pakistan. J public Health Policy 29: 207-225.

- Delage G, Infante-Rivard C, Chiavetta JA, Willems B, Pi D, et al. (1999) Risk factors for acquisition of hepatitis C virus infection in blood donors: results of a case-control study. Gastroenterology 116(4): 893-899.

- Zou S, Dorsey KA, Notari PE, Foster AG, Krysztof ED, et al. (2010) Prevalence, incidence, and residual risk of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus infections among United States blood donors since the introduction of nucleic acid testing. Transfusion 50(7): 1495- 1504.

- Abdelaal M, Rowbottom D, Zawawi T, Scott T, Gilpin C (1994) Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus: a study of male blood donors in Saudi Arabia. Transfusion 34(2): 135-137.

- Lema AM, Cox EA (1992) Hepatitis C antibodies among blood donors in Qatar. Vox Sang 63(3): 237.

- Council GH: Regulations of expatriate’s examinations for residency permit 2019.

- Public Health Department -MOH K: Ports and borders health Annual report 2017.

- Lavanchy D (2011) Evolving epidemiology of hepatitis C virus. Clin Microbiol Infect 17(2): 107-115.

- Mohd HK, Groeger J, Flaxman DA, Wiersma TS (2013) Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: new estimates of agespecific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology 57(4): 1333-1342.

- Qureshi H, Bile KM, Jooma R, Alam SE, Afridi RUH (2010) Prevalence of hepatitis B and C viral infections in Pakistan: findings of a national survey appealing for effective prevention and control measures. East Mediterr Health J 16: S15-S23.

- Mostafa A, Taylor MS, El-Daly M, El-Hoseiny M, Bakr I, et al. (2010) Is the hepatitis C virus epidemic over in Egypt? Incidence and risk factors of new hepatitis C virus infections. Liver Int 30(4): 560-566.

- Akhtar S, Moatter T (2004) Intra-household clustering of hepatitis C virus infection in Karachi, Pakistan. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 98(9): 535-539.

- Akhtar S, Moatter T, Azam IS, Rahbar HM, Adil S (2002) Prevalence and risk factors for intrafamilial transmission of hepatitis C virus in Karachi, Pakistan. J viral Hepat 9(4): 309-314.

- Arif M, Al-Swayeh M, Al-Faleh ZF, Ramia S (1996) Risk of hepatitis C virus infection among household contacts of Saudi patients with chronic liver disease. J Viral Hepatitis 3(2): 97-101.

- Thakral B, Marwaha N, Chawla KY, Sharma A (2006) Prevalence & significance of hepatitis C virus (HCV) seropositivity in blood donors. Indian J Med Res 124(4): 431-438.

- Mohamoud YA, Riome S, Abu-Raddad JL (2016) Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus in the Arabian Gulf countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence. International journal of infectious diseases. Int J Infect Dis 46: 116-125.

- Chaabna K, Cheema S, Abraham A, Alrouh H, Lowenfels BA, et al. (2018) Systematic overview of hepatitis C infection in the Middle East and North Africa. World J Gastroenterology 24(7): 3038-3054.

- Allison RD, Conry-Cantilena C, Koziol D, Schechterly C, Ness P, et al. (2012) A 25-year study of the clinical and histologic outcomes of hepatitis C virus infection and its modes of transmission in a cohort of initially asymptomatic blood donors. J Infectious Dis 206(5): 654-661.

- Frank C, Mohamed KM, Strickland GT, Lavanchyet D, Arthur RR, et al. (2000) The role of parenteral antischistosomal therapy in the spread of hepatitis C virus in Egypt. Lancet 355(9207): 887-891.

- Guerra J, Garenne M, Mohamed KM, Fontanet A (2012) HCV burden of infection in Egypt: results from a nationwide survey. J Viral Hepat 19(8): 560-567.

- Perumalswami PV, Miller WDF, Orabee H, Regab A, Adams M, et al. (2014) Hepatitis C screening beyond CDC guidelines in an Egyptian immigrant community. Liver Int 34(2): 253-258.

Article Type

Research Article

Publication history

Received Date: October 03, 2022

Published: October 18, 2022

Address for correspondence

Najla Al-Ayyadhi, Public Health Specialist, Directorate of Public Health, Ministry of Health, Kuwait

Copyright

©2022 Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science, All rights reserved. No part of this content may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means as per the standard guidelines of fair use. Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

How to cite this article

Najla Al-Ayyadhi. Hepatitis C Virus Infection and Risk Factors Among Immigrants Asymptomatic Blood Donors in Kuwait: A Case-Control Study. 2022- 4(5) OAJBS. ID.000501.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of cases and controls studied for their association with serological evidence of infection with hepatitis C virus among blood donors in Kuwait.

Table 2: Chi-square analysis of risk factors associated with hepatitis C virus infection among asymptotic blood donors in Kuwait.

Table 3: Multivariable logistic regression model of factors associated with HCV seropositivity among blood donors in Kuwait.