Teenage Pregnancy, what is its Impact on Latin America?

ABSTRACT

Adolescent pregnancy in the world has an incidence rate of 41 per thousand women between 15 and 19 years of age; however, in the Latin American and Caribbean region these figures are higher, reaching at least 67 per thousand women and unlike the global trend, it is expected that in the region this value will continue to rise. Through various studies it has been identified that the risk factors associated with the occurrence of this event are mainly low schooling and low socioeconomic level, early initiation of sexual relations, among others. Additionally, it has been established that adolescent pregnancy brings with it risks to the health of both the woman and the newborn, but even more worrisome it leads to the perpetuation of poverty, to a decrease in schooling in the long term and therefore to a lower income expectation among women who have children before the age of 20. Individual interventions have not been able to demonstrate significant changes in the decrease in adolescent birth rates, since as it is a multifactorial problem, it must be addressed with multidisciplinary interventions. Through this review, it is intended to expand all the aspects and nuances associated with this problem and to clarify which are the most effective mechanisms to generate an impact on the reduction of adolescent births. Since it is a multifactorial problem, it must be addressed with multidisciplinary interventions. Through this review, it is intended to expand all the aspects and nuances associated with this problem and to clarify which are the most effective mechanisms to generate an impact on the reduction of adolescent births. Since it is a multifactorial problem, it must be addressed with multidisciplinary interventions. Through this review, it is intended to expand all the aspects and nuances associated with this problem and to clarify which are the most effective mechanisms to generate an impact on the reduction of adolescent births.

KEYWORDS

Adolescent; Pregnancy; Fertility; Schooling; Maternity; Childbirth

INTRODUCTION

Adolescence is defined as the age period that occurs between childhood and adulthood, according to the WHO [1], this stage is between 10 and 19 years of age. It is in this period in which a series of physical, psychological, social and cognitive changes occur, among which changes in sexual behavior stand out, which can act as protective or risk factors in health. It is for this reason that concern is growing regarding adolescent pregnancies in the Latin American and Caribbean region, since it is estimated that this region currently ranks second in the adolescent birth rate [2], being second only to the African continent. Around the world, the adolescent birth rate is 41 per 1,000 women between the ages of 15 and 19, compared to Latin America, where an average of 67 pregnancies is calculated for every 1,000 women between 15 and 19 years of age [3], it should be noted that at least 95% of adolescent pregnancy cases occur in low- and middle-income countries [4]. Additionally, it has been possible to identify that of the 1.2 million unwanted pregnancies, at least half occur in the adolescent period and that up to 50% of women who give birth for the first time in this region correspond to adolescents [5].

Despite the fact that worldwide the figures for adolescent pregnancies between 1990 and 2015 have decreased drastically, this trend has not been reflected in this region, since according to UNFPA “Latin America is the only region in the world where births to women children under 15 years of age are on the rise, and it is expected to increase further towards the year 2030” [6]. Efforts have been made to search for those predisposing or risk factors in this situation, reaching the conclusion that it is not possible to associate a single cause with the high numbers of pregnancies in Latin America. It has been possible to identify that low schooling, cohabitation or marriage, the early initiation of sexual relations, cultural and economic aspects are the main factors that influence the increase in this problem.

Regarding the educational level, it has been established that, for each year of schooling, there is a decrease between 5 and 10% in the adolescent pregnancy rate. In addition, not only general schooling was identified as a protective factor, but also knowledge of sexual rights, contraceptive methods, development of life skills, self-esteem, self-sufficiency and sexual negotiation capacity, which allow adolescents to have a greater reflection, responsibility, autonomy, and sequentially a decrease in pregnancies at this age is generated. It has been discovered that a greater knowledge of ovulatory cycles, the adequate use of contraceptives, and a greater perception of the risks and consequences of pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium can potentially reduce the risk of adolescent pregnancy. Regarding access to health services, some limitations are evident, because for adolescents there is no easy access to them, either due to ignorance, fear of confidentiality of information, fear of being judged, ignorance of the health personnel; This is why it was possible to determine that individual interventions are less effective compared to community, family, school, social and regional interventions. Through multiple studies it was evidenced that in Latin America adolescents start sexual activity earlier and that only a small proportion effectively use planning methods both for the prevention of pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections [7]. It is estimated that adequately providing modern contraceptive methods to women between the ages of 15 and 19 could prevent at least 2.1 million unwanted pregnancies around the world [8].

Regarding the social and cultural factors that influence the increase in adolescent pregnancies, it is possible to show that a significant proportion of adolescent pregnancies were wanted, it is considered that this is caused by gender roles, social recognition (obtaining an adult status ), demonstrate fertility, economic opportunities and a decrease in the labor and professional offer; It is also possible to highlight that the roles associated with “masculinity” encourage the non-use of condoms in male adolescents. From another perspective, it is striking that, in Latin American countries, the influence of religion causes fear and increases taboos towards sexuality, which limits adolescents from accessing quality information and modern contraceptive methods. for fear of being judged or reprimanded for initiating sexual activity early. In addition to the aforementioned, it should be taken into account that, in the social context of Latin American countries, a part of adolescent pregnancies are the product of sexual violence and gender-based violence, associated with illegality or little access to the voluntary termination of pregnancy, which negatively contributes to the number of women who have had at least one child before the age of 20 [9,10].

Concern about the increase in adolescent pregnancy rates lies in the increased risks and complications associated with the physical, psychosocial and economic immaturity of women between 15 and 19 years of age; An adolescent pregnancy is considered to represent an increased risk of perinatal maternal death, pregnancy loss, preterm delivery, preeclampsia, anemia, low birth weight [1,5]; Additionally, it should be noted that a percentage of pregnant adolescents resort to unsafe abortions, increasing their risk of death due to complications associated with these procedures [7,9,11]. Not only are complications inherent to pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium present, it has been shown through studies that adolescent mothers present an increased risk of longterm complications such as cardiovascular diseases, functional limitations, incontinence and chronic pain [9]. Regarding the economic and social consequences, it is possible to demonstrate that adolescent pregnancies perpetuate intergenerational poverty; This is due to the fact that there is an increase in school dropouts among women who have pregnancies during adolescence, there is a lower probability of completing secondary school studies [12] and less admission to higher education [13]. , which consequently generates a decrease in educational achievement and the income potential of the family nucleus (8), resulting in an increase in the population of women between 15 and 19 years of age who are not working or studying [14]. it is possible to demonstrate that adolescent pregnancies perpetuate intergenerational poverty [8,9]; This is due to the fact that there is an increase in school dropouts among women who have pregnancies during adolescence [7]. Finally, multiple studies evaluated the effects of the interventions carried out in the adolescent population, in the reduction of the birth rate in women between 15 and 19 years of age, through which it was identified that those interventions with the greatest impact were those designed to improve the socioeconomic level of adolescents and those who encourage permanence in educational institutions and encourage a higher level of schooling [15-19]. Despite the fact that the impact of individual educational interventions was evaluated, the results were not conclusive, nor did they show an impact on the birth rate in adolescents. However, it should be noted that when these interventions were carried out in a family and community way.

METHODOLOGY

The design of this study was carried out through a systematic review of the evidence available in the scientific literature on adolescent pregnancy in the Latin American and Caribbean region, which included those in which the current situation in the region, the risk or predisposing factors towards this problem, consequences and the factors considered protective or that contribute to the reduction of the figures in this regard. A bibliographic search was carried out through the different scientific databases such as ScienceDirect, Pubmed, Elsevier, Scielo and Medline, including those studies that have been carried out in the last decade, in addition to those that are focused on the Latin American and Caribbean region. In order to clarify all the nuances involved in this problem. Additionally, demographic data was taken from WHO/ PAHO databases. Articles published before 2010 and those that do not focus on the region of interest were excluded from the selection.

RESULT AND DISCUSSION

According to the WHO (World Health Organization) and the UNFPA (United Nations Population Fund), the pregnancy rates in adolescents between 15 and 19 years of age in the world are 42 per 1000 women, this value being exceeded by the rates of adolescent pregnancy in Latin America and the Caribbean, which is estimated to reach at least 67 per 1,000 women between the ages of 15 and 19 [20]. According to what was reported by Decat [5] approximately 600,000 unplanned pregnancies occur during adolescence and up to 50% of women in this area had their first child during this stage. Despite the fact that there was a decrease in the adolescent birth rate worldwide, it is considered that this decrease is due to the decrease in subsequent births in adolescent mothers, which agrees with what was reported by Pleson et al. [8] who indicate that there is a decrease from 4 births per woman to 2.2 births per woman between 2010 and 2015. An evaluation of the adolescent pregnancy rate was also carried out, represented in the number of pregnancies per thousand women between 15 and 19 years of age in Peru, Haiti, Colombia, Bolivia, Nicaragua, which again coincides with what was reported in the study by Pleson et al. [8] where a rate of adolescent pregnancies in Centroa which again coincides with what was reported in the study by Pleason et al. [8]; Figure 1 representing this last region the highest values compared to the average for the Latin American region and being much higher than the world average, for which it is considered that Latin America is the only region with a growing trend of adolescent pregnancies [21,22].

According to Rodriguez [23] it is estimated that 16% of fertility among women is given by adolescents between 15 and 19 years of age in Latin America, but despite this it can be established see that at the local level there are countries like Colombia where it is estimated that at least 23% of children are the product of adolescent mothers [24]; In Peru, approximately 30.5% of women between the ages of 15 and 19 have had at least one child or were pregnant in 2017, despite this, Sanchez and Favara state that in the same period of time this percentage was 14.3%. It is possible to deduce from this that in the Latin American and Caribbean region adolescent pregnancies are a growing problem, in addition that there is a limitation to access to information, since the statistics do not include pregnant adolescents who had abortions. clandestine and did not include male adolescents whose partners are going through pregnancies in this age range.

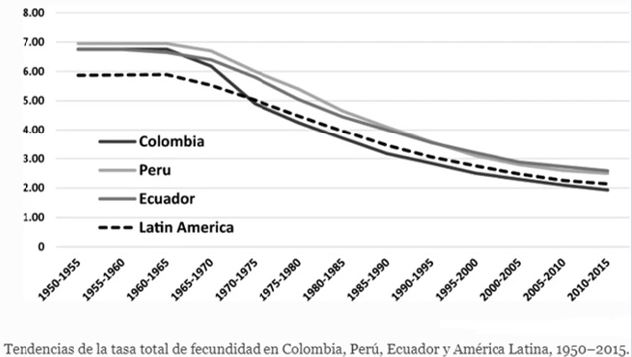

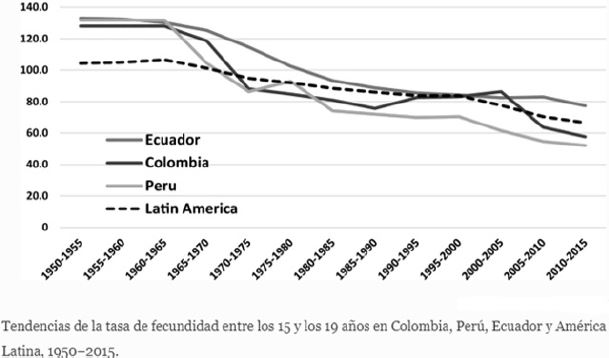

According to the study “Increasing Educational Disparities in the Timing of Motherhood in the Andean Region: A Cohort Perspective” there has been evidence in countries such as Colombia, Ecuador and Peru a decrease in the general rate of embarrassment (Table 1); [25]. However, this contrasts with a stagnation in adolescent pregnancy rates (Figure 2,3), which were more ascending in populations with medium and low economic resources, which is consistent with the findings in the study “Teen Pregnancy: Health Effects and Guarantee of Rights” where it was evidenced that adolescent fertility is 4 times higher in low socioeconomic strata and countries developing.

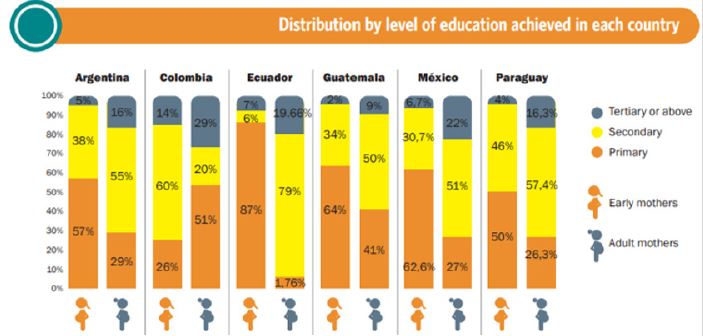

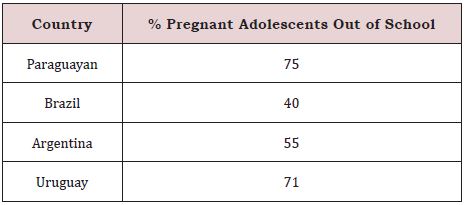

Regarding the factors predisposing to the increase in adolescent pregnancies, it is low schooling, or lack of literacy. It has been shown that total illiteracy can increase the risk of adolescent pregnancy by up to 44% (2); In addition, in the multilevel analysis “Factors associated with pregnancy desire among adolescent women in five Latin American countries: a multilevel analysis” it was established that for each year of schooling there is a reduction of between 5 and 10% in the adolescent pregnancy rate. In the same way, Atienzo agrees that adolescent pregnancy rates are higher when the educational level is low. According to Reina and Castelo-Branco. The majority of pregnant adolescents were outside the educational system at the time of conception (Table 1). It can be considered that this is a common trend in the region since Sanchez [26] affirms that “in countries like Peru and Paraguay, girls are at greater risk of becoming adolescent mothers when they face poor quality education”; In addition, in Colombia it was possible to show that pregnancy is more likely to occur once school dropout occurs. A case-control study conducted in Colombia reported a higher risk of adolescent pregnancy associated with public education; however, this is considered to be more closely related to socioeconomic status [27]. In her study, Batyra [25] states that 25% of women with less schooling make an earlier transition to motherhood.

The early initiation of sexual relations has also been shown to be an influential factor and increases the risk of adolescent pregnancy. According to Decat [7] the age of initiation of sexual activity in adolescents is increasingly earlier, only a small percentage is using modern contraceptive methods, this data is consistent with that evidenced by Reina and Castelo-Branco [11] who were able to identify that by 2013 at least 52% of adolescents between 15-19 years old had already initiated sexual activity; findings that were consistent in Colombia, where an early onset of sexual activity is shown as a significant factor; additionally, various studies agree that there is underreporting of the onset of sexual activity as a consequence of sexual and gender violence. From this it is inferred that there is an increased risk associated with the early initiation of sexual activity and this raises concern about the lack of access, ignorance and limitations on the use of contraceptives. In the study “Influence of Sexual and Reproductive Health Literacy on Single and Recurrent Adolescent Pregnancy in Latin America” it is evident that those women who are unaware of the functioning of the ovulatory cycle and have never used a contraceptive method are those with the highest risk.

Chandra-Mouli et al. [5] explain that there is a decrease in access to contraceptives, which is largely caused by fear of disclosure of information (confidentiality), fear of being judged, family taboos and social and the lack of training of health personnel in adolescent care. Decat [7] in their study show that women between 14 and 24 years old protected with some planning method in Nicaragua was 11.4%, in Bolivia 19% and in Ecuador it is estimated that only 50% of the 43% of adolescents who had sex without a condom and 70% did not use a condom in their last sexual relationship; This is also supported by research carried out in Argentina where it is considered that of the adolescents who gave birth in 2014, 79% did not use any contraceptive method at the time of conception and in Mexico [10]. Only 59% of sexually active youth used planning methods. Pleson et al. [8] reported in their study that meeting the contraceptive needs of the population of women aged 15-19 years could prevent millions of unintended pregnancies, induced abortions and thousands of maternal deaths per year. A great limitation to the access to contraceptives lies in the disapproval by religious movements, conservative politicians, pro-life, profamily, and professional associations before making contraceptive methods generally available and educating on gender ideology, as evidenced by Fraser [28] in your research.

Regarding access to information, Castelo-Branco [11] in their research showed that adolescents obtain information on planning to a greater extent through the school and from their peers, leaving trained professionals in last place [28]. In the case of Latin America, various studies support the idea that early marriage is also an influential factor in adolescent pregnancies [29]. 28% of women in developing countries marry before the age of 18, reaching in Latin America and the Caribbean up to 37%, this includes marriages for economic convenience and those that are carried out consensually, Additionally, it showed that 36% of adolescents in Latin America and the Caribbean who require a contraceptive method (either because they are married or sexually active) are not having access to them. Based on this, the decrease in access to contraceptive methods and the lack of knowledge about sexual and reproductive health are identified as a factor that negatively influences the increase in adolescent pregnancy rates. One of the most common aspects to highlight during the investigation are the possible consequences of adolescent pregnancies, not only regarding physical health but also the psychosocial development of young people. Dongarwar [2] in their study report that adolescent pregnancy increases the risk of maternal-perinatal complications such as preeclampsia, anemia, malnutrition, pregnancy loss, low birth weight, and perinatal death. Regarding the long-term effects, Aires da Camara et al. [9] there is an increased risk of respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, chronic pain and incontinence. The study “Adolescent pregnancy in Latin America and the Caribbean” shows that maternal mortality associated with complications of pregnancy and childbirth was the fourth cause of death in women between 10 and 24 years of age.

In Argentina, hospitalization for abortion has had an increase of 57%, of which it should be noted that 40% occurred in children under 20 years of age [28]. Despite the fact that adolescent pregnancy has multiple consequences for physical health, the economic and social repercussions are even more alarming.

According to the study “Data gaps in adolescent fertility surveillance in middle-income countries in Latin America and South Eastern Europe: Barriers to evidence-based health promotion”, adolescent pregnancies contribute to perpetuating transgenerational poverty, however according to Harvey [3] it is not possible to affirm if poverty is a cause or consequence of adolescent pregnancy”, however this same study shows that the earlier the age of pregnancy, the greater the probability of poverty; In both Paraguay, Brazil and Argentina there is a larger population of pregnant adolescents who belong to a low socioeconomic level compared to those who belong to a high level. The available data shows that adolescent mothers have a lower level of formal education; In Peru, 43% have not finished basic secondary education and 55% of adolescents in the first trimester of pregnancy were not in school. Campos Vazquez [30] found that in Mexico 41% of mothers between 14 and 19 years of age did not complete their academic studies and that there was a short-term reduction in schooling between 0.6 and 0.8 years and a long-term reduction of 1.2 years. It has been considered that this decrease in schooling increases the number of adolescent mothers with lower per capita income. In addition, in Colombia, Aguero [14] documents that being an adolescent mother has a negative effect on work results. Favara [13] in their study also consider that female adolescent mothers are less likely to enroll in school or embark on the world of work. In Colombia, Low expectations about the benefits of continuing education [25].

Favara et al. [31] find that those women who delay childbearing have greater educational, economic, and social opportunities in Mexico; In addition, a study carried out in Chilean homes shows that adolescent fertility is determinant in school dropout and adolescent mothers have 34% fewer opportunities to graduate from secondary school and 49% to access higher education (Figure 4). Through this, it is considered that despite the health effects of adolescent pregnancy, the socioeconomic effects are more worrisome, since the decrease in schooling brings with it less job opportunity and a decrease in income, perpetuating poverty in the populations and all the consequences derived from it.

Based on the identification of risk and predisposing factors for adolescent pregnancy, research has been carried out such as that carried out by Favara [13] in which it is shown that in Chile an increase in the school day leads to a reduction of 3 % of adolescent pregnancies since adolescents have a greater awareness of planning methods, consequences of pregnancy, responsible decision-making and a greater educational and professional aspiration. In favor of this position is Rodriguez [23] who carried out a systematic review in which he highlights that “forcing women to spend more time in school significantly reduces the probability of maternity in adolescence” and regarding the reasons why which this decrease occurs, agrees with Favara.

The study “The effect of education on teenage fertility: causal evidence for Argentina” supports the argument that an increase in years of schooling is useful for reducing adolescent pregnancies, increasing from 0.24 to 0.27 additional years, impacting on a decrease in the adolescent fertility rate from 26.9 to 35.5 per thousand points, also evidenced that the increase in adolescent enrollment had an impact on the reduction of fertility for this age range. As previously mentioned, a greater impact of family, social, community and regional interventions on the disclosure of sexual and reproductive health in adolescents has been shown, above interventions individually, This is why, despite the fact that a study carried out in Paraguay showed good results with the implementation of health units, it was not possible to attribute the entire decrease in adolescent pregnancies to this intervention; Similarly, in the study by Meremikwu et al. [16] contraceptive education was addressed, however it was not possible to demonstrate a reduction in adolescent pregnancies attributable to this strategy.

Regarding the interventions that presented the greatest effectiveness in reducing adolescent pregnancies, the transfer of resources and cash by government entities, whether conditional on school attendance or not, was the one that had the greatest impact; It is considered that this is because it increases access to information, assistance to health services, school environments, an improvement in economic conditions and a substitution of basic needs, which is supported by the research by Favara [31]. Due to the above, adolescent pregnancy can be considered a multifactorial problem, so the approach must be carried out from multiple aspects to achieve a real impact.

CONCLUSION

Pregnancy rates for women between 15-19 years of age in Latin America and the Caribbean, in contrast to world rates, present an increase, being located in second place after the African continent, this trend is caused by different aspects of the territory such as underdevelopment of the region, the low economic income of the population, the non-schooling of adolescents, thus being a multidimensional problem. It should be taken into account that an underreporting of this problem is evident, due to the scarcity of information and some populations that have been excluded from the studies, since in the majority of the population to be studied is between 15 and 19 years old, However, the period of adolescence begins at age 10 according to the WHO, therefore women between 10 and 14 years of age with adolescent pregnancies are not registered, in addition, those women who undergo clandestine abortions who for fear of being judged do not report adolescent pregnancies at the time of conducting the investigations; Another important nuance is that male adolescents whose sentimental partners are pregnant are not taken into account, but instead all the studies focus on the population of female adolescents. As already mentioned, adolescent pregnancy has multifactorial characteristics, however, in the region the main risk factor evidenced is low schooling and lack of access to quality educational services. Regarding the main consequences of pregnancy during adolescence, it is identified that women who have had adolescent pregnancies have a lower probability of completing their basic secondary studies and accessing higher education, thus reducing job opportunities and access to an economic remuneration that promotes an improvement in their quality of life, thus prolonging the cycle of intergenerational poverty. Despite the fact that multiple interventions have been carried out in order to reduce these rates of adolescent pregnancy and despite the fact that educational interventions have been very useful, since this is a multifactorial problem that leads to physical, psychosocial, and economic consequences, among others, it is generates the need to approach it from a global perspective, focused on the region and its problems, in order to intervene in all those aspects that contribute to increasing the risk.

REFERENCES

- World Health Organization (2022) Salud del adolescente.

- Dongarwar D, Salihu HM (2019) Influence of Sexual and Reproductive Health Literacy on Single and Recurrent Adolescent Pregnancy in Latin America. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 32(5): 506-513.

- Neal S, Harvey C, Chandra-Mouli V, Caffe S, Camacho AV (2018) Trends in adolescent first births in five countries in Latin America and the Caribbean: disaggregated data from demographic and health surveys. Reprod Health 15(1): 146.

- Estrada F, Suárez-López L, Hubert C, Allen-Leigh B, Campero L, et al. (2018) Factors associated with pregnancy desire among adolescent women in five Latin American countries: a multilevel analysis. BJOG 125(10): 1330-1336.

- Córdova Pozo K, Chandra-Mouli V, Decat P, Nelson E, De Meyer S, et al. (2015) Improving adolescent sexual and reproductive health in Latin America: reflections from an International Congress. Reprod Health. 12: 11.

- (2017) UNFPA. Embarazo Adolescente.

- Decat P, Nelson E, De Meyer S, Jaruseviciene L, Orozco M, et al. (2013) Community embedded reproductive health interventions for adolescents in Latin America: development and evaluation of a complex multi-centre intervention. BMC Public Health 13: 31.

- Caffe S, Plesons M, Camacho AV, Brumana L, Abdool SN, et al. (2017) Looking back and moving forward: can we accelerate progress on adolescent pregnancy in the Americas? Reprod Health 14(1): 83.

- Sentell T, da Câmara SMA, Ylli A, Velez MP, Domingues MR, et al. (2019) Data gaps in adolescent fertility surveillance in middle-income countries in Latin America and South Eastern Europe: Barriers to evidence-based health promotion. South-East Eur J Public Health 11: 214.

- Hubert C (2022) Factors associated with pregnancy and motherhood among Mexican women aged 15-24. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 35(6): e00142318.

- Reina M, Castelo-Branco C (2018) Teenage pregnancy: A Latin-American concern. Obstetrics Gynecol Res 1(4): 085-093.

- Barbara F (2020) Adolescent pregnancy in Latin America and the Caribbean. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health 4(5): 356-357.

- Alan Y Marta Favara (2019) Consequences of teenage childbearing in Peru: is the extended school-day reform an effective policy instrument to prevent teenage pregnancy? Working Paper, Oxford: Young Lives, 185.

- Agüero JM (2021) Misallocated talent: Teen pregnancy, education and Job Sorting in Colombia. Caracas: CAF.

- Hindin MJ, Kalamar AM, Thompson TA, Upadhyay UD (2016) Interventions to prevent unintended and repeat pregnancy among young people in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review of the published and gray literature. J Adolesc Health 59(3 Suppl): S8- S15.

- Oringanje C, Meremikwu MM, Eko H, Esu E, Meremikwu A, et al. (2016) Interventions for preventing unintended pregnancies among adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2(2): CD005215.

- Alzúa ML, Velázquez C (2017) The effect of education on teenage fertility: causal evidence for Argentina. IZA J Develop Migration 7(7).

- Sanz-Martos S, López-Medina IM, Álvarez-García C, Álvarez-Nieto C (2019) Effectiveness of educational interventions for the prevention of pregnancy in adolescents. Aten Primaria 51(7): 424-434.

- Ávalos DS, Recalde F, Cristaldo C, Puma AC, López P, et al. (2018) Impact of the family health units strategy for primary health care on adolescent pregnancy rate in Paraguay impacto da Estratégia das Unidades de Saúde da Família para Atenção Primária a Saúde na taxa de gravidez na adolescência no Paraguai. Rev Panam Salud Publica 42: e59.

- UNFPA. Socioeconomic consequences of adolescent pregnancy in six Latin American countries. Implementation of the MILENA methodology in Argentina, Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico and Paraguay. United Nations Population Fund - Latin America and the Caribbean Regional Office. Panama. 2020.

- Fátima E, Erika E (2021) A Rapid Review of Interventions to Prevent First Pregnancy among Adolescents and Its Applicability to Latin America. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 34(4): 1491-503.

- Castañeda PJ, Santa-Cruz-Espinoza Henry (2021) Risk factors associated with pregnancy in adolescents. Enferm Glob 20(62): 109-128.

- Rodríguez Ribas C (2021) Adolescent pregnancy, public policies, and targeted programs in Latin America and the Caribbean: a systematic review. Rev Panam Salud Publica 45: e144.

- (2012) Teen pregnancy: Health effects and guarantee of rights.

- Batyra E (2020) Increasing educational disparities in the timing of motherhood in the Andean region: A Cohort Perspective. Popul Res Policy Rev 39: 283-309.

- Sánchez I (2020) Impact of the salud mesoamerica initiative on adolescent pregnancy in Costa Rica: new evidence on multisectoral interventions.

- Lina SMD, Latorre C, José TR (2014) Risk factors for adolescent pregnancy in Bogotá, Colombia, 2010: a case-control study. Rev Panam Salud Publica 36(3): 179-184.

- Barbara F (2020) Adolescent pregnancy in Latin America and the Caribbean. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health 4(5): 356-357.

- Darroch JE (2016) Adding it up: Costs and benefits of meeting the contraceptive needs of adolescents. Guttmacher Institute, New York, USA.

- Arceo-Gomez, Eva O, Raymundo M (2014) Teenage Pregnancy in Mexico: Evolution and consequences. Latin American Journal of Economics 51(1): 109-146.

- Azevedo JP, Favara M (2012) Teenage pregnancy and opportunities in Latin America and the Caribbean: On teenage fertility decisions, poverty and economic achievement.

Article Type

Research Article

Publication history

Received Date: December 06, 2022

Published: March 06, 2023

Address for correspondence

Cindy Paola Cerro Martinez, Gynecologist, Universidad Libre, Colombia

Copyright

©2022 Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science, All rights reserved. No part of this content may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means as per the standard guidelines of fair use. Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

How to cite this article

Cindy Paola CM, Gabriela AC, Jefferson Augusto SS, Carlos Jose CH, Monica Yulieth MO, et. al. Teenage Pregnancy, what is its Impact on Latin America?. 2023- 5(2) OAJBS.ID.000552.

Figure 1: Adolescent fertility rate in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Figure 2: Total fertility rate trend in Latin America.

Figure 3: Total adolescent fertility rate trend in Latin America.

Figure 4: Educational level among adolescent mothers vs. adult mothers.

Table 1: Percentage of pregnant adolescents outside the school system.