Perspectives on an Iterative and Bidirectional Information System and its Role in Improving Health Outcomes in Western Kenya

ABSTRACT

Background: A perennial problem in information systems is the unidirectional flow of information. Bidirectional information

systems are mechanisms by which consumers and providers generate, discuss and use information at each level of data collection.

This paper describes opportunities in the health service delivery system for bidirectional information flow that can be established

as part of the health information system to inform decisions, planning, and action by both providers and consumers of care.

Methods: The study was quasi-experimental and involved pre- and post-intervention, cross-sectional surveys at intervention

and control sites. The intervention was a Community Based Health Information System. Quantitative and qualitative data were

collected. The surveys covered five health facilities in the intervention sites and five in the control sites in each of the six study

districts. Five clients were interviewed at each intervention and control health facility. Communities served by the selected health

facilities were included in household cluster sample surveys. Thirty clusters of 10 households, each with under-five children, were

included in each community served by the selected health facilities. Quantitative data were cross tabulated to compare health

outcomes at intervention and control sites. A content analysis was performed on the qualitative data; themes and sub-themes that

identified opportunities for bidirectional information-sharing were identified.

Results: We identified five nodal points in the health system that provide opportunities for bidirectional information sharing

at the household, community, and health facility levels. Immunization coverage, skilled delivery, water treatment, and latrine use

improved more at the intervention than control sites. Where all of the mechanisms were implemented, there was better performance

in outcomes.

Conclusion: A conscious engagement of service providers and consumers in dialogue, using available health system information

to iteratively inform decisions and actions, improves health outcomes.

KEYWORDS

Community based; Information systems; Bidirectional dialogue; Health systems performance

ABBREVIATIONS:

CBHC: Community Based Health Care; CBHIS: Community Based Health Information System; CHEW: Community Health Extension Workers; CHW: Community Health Workers; DHMT: District Health Management Teams; MCH: Mother and Child Health; NACOSTI: National Commission for Science, Technology, and Innovation; SPSS: Statistical Package for Social Sciences; WHO: World Health Organization

INTRODUCTION

A perennial problem in information systems is the unidirectional flow of information from care providers to district and national decision-makers [1]. While the unidirectional flow of evidence is important, it is insufficient to stimulate health care improvements. This is because a unidirectional approach suggests that the solutions to problems lie entirely with decision-makers rather than with communities and service providers. It leaves them feeling disengaged in the process of finding solutions and does not increase consumer demand for better services. Furthermore, unidirectional information flows do not provide a means for all those concerned to reflect on information, offer their interpretation of causes, and consider solutions. When information is not directly linked to local decisions, health workers view data collection and reporting as onerous and futile [2]. This compromises data quality. Data collection used only for reporting requirements, makes health workers disengage from analysing data and using it for local decision-making and timely action. Similarly, data collected for research purposes, with results used only for academic purposes limits the usefulness of such data. Failure to engage communities in the data collection, analysis, and application cycle, leads to scepticism and cynicism [2].

Historically, service delivery, collection, and reporting of health information in Kenya ended at the health facility level, leaving a gap between the household and the health facility [3]. The development of a Community Based Health Information System (CBHIS) aimed to address this gap. The CBHIS has a number of important features. First, both health facility- and community-based health workers collect and submit health information in this national system using a tool developed by the Kenyan Government Ministry of Health. A prior study by Otieno et al. [4] demonstrated that information collected by community-based health workers was of adequate quality for use as part of the national health information system. Second, community health information collected is intended for analysis and use by the community, service providers, and managers for dialogue, decision-making, planning joint actions for health improvement, and monitoring and evaluation of services at community level.

This study set out to identify and describe opportunities CBHIS provides for iterative bidirectional sharing of information at multiple levels of service delivery, and its contribution to improving the health system’s performance, by bridging the interface between the community and the system. This paper describes the two-way information sharing opportunities in CBHIS, and its effectiveness in improving the health system governance, management, service delivery, and health outcomes.

METHODOLOGY

The study design was quasi-experimental. Three intervention and three control districts in Western Kenya were purposefully selected and matched on socio-cultural and socio-economic factors. We carried out pre and post-intervention assessments of governance, management, service delivery, and health outcomes in intervention and control sites in all six districts. We implemented the CBHIS intervention in three districts but carried out baseline and follow-up assessments at intervention and control districts. We collected qualitative and quantitative data at intervention and control sites to compare health system performance and information sharing opportunities.

All study participants provided a written informed consent to participate in the study. The study involved human beings and was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki ethics guidelines and was approved by Great Lakes University Research Ethical Review Board and National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI). The study protocols and informed consent forms were reviewed and approved by Great Lakes University of Kisumu Ethical Review Board. The national research clearance certificate and permit was obtained from National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI).

The Intervention

The overall intervention involved the implementation of Community Based Health Care (CBHC). This paper focuses on the CBHIS, which was a core element of this overall program. CBHC involved organizing communities into community health units with community health committees linked to health facility committees through representation. CBHC also involved training and supporting Community Health Workers (CHWs) and Community Health Extension Workers (CHEWs). CHWs were volunteers trained and supervised by CHEWs who were health professionals. The CHWs were identified and supported by the community and were responsible for maintaining the CBHIS and running village health activities. We implemented the CBHIS framework using the 2006 Kenya Government Community Health Strategy guidelines [5]. CBHIS generated not only data on health indicators but also information about community dialogue. The CBHIS strategy attempted to build a common understanding of information and action planning at all levels, starting with the household. The CBHIS involved registering households; it was updated every six months. The register collected demographic, health seeking behavior, health status, and health care coverage data including immunization, antenatal care, skilled delivery, water treatment, latrine use, and use of insecticide treated nets. This information for each household was contained on a single page. The register was left at the household to be used by the CHWs, who visited each household every three months, to discuss the health situation of the household displayed on the register. Each household received four such visits a year. The CHW, with the support of the CHEW and research assistants, analyzed the data contained in the registers, displayed the results on village chalk boards, and used it for community unit monthly dialogue sessions. Thus, repeated two-way discussions between service providers and community members, based on available data, took place at the household level every three months, at the community level monthly, and at the health facility level every three months. The iterative dialogue process has been explained in greater detail elsewhere [6].

The community health committees participated in dialogue sessions at both community and health facility levels. Community members and their leaders, health service providers, and representatives of other related sectors were invited to the dialogue forums at monthly community unit dialogue and quarterly divisional dialogue days. At a dialogue, session results from CBHIS were presented and discussed by all stakeholders. The dialogue process led to the identification of health indicators needing improvement and specific actions identified. This was followed by action planning by all stakeholders, each one identifying their role in the improvement effort.

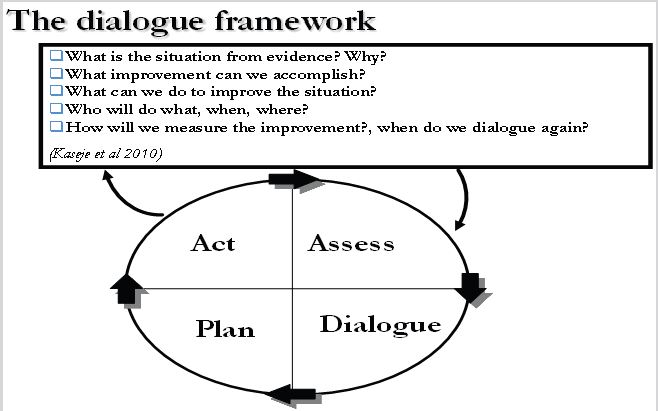

CHEWs summarized the household data on chalkboards as well as on summary sheets for reporting to the local health facility. For the purpose of the study, data collected by CHWs were validated by a technical research team that collected the same data on 10% of the households, to ensure data quality. The chalkboard data was used for dialogue between communities on the one hand and service providers and researchers on the other. Summary data submitted to the health facility was discussed at management committees, which included community representatives. CBHIS enabled community members to follow up on the progress of planned activities towards the agreed set of objectives. The iterative mechanism central to this process is presented on Figure 1.

We carried out a health facility survey to assess governance, management, service delivery, and sample household surveys to measure health outcomes at the beginning and the end of the intervention, to measure changes in these indicators during the period of the study (2011-2014).

Sampling

Health facility Surveys were administered in purposively selected health facilities serving communities implementing CBHC. In each study district we included one hospital (level 4), three health centers (level 3), and one dispensary (level 2), as defined in the Health Sector Strategic Plan II of 2005 [7], All selected health facilities served the community health units included in the household surveys. To assess clients’ satisfaction, we randomly selected 30 clients from the daily attendance register at the hospital, 20 at the health center, and 10 at dispensary levels both intervention and control districts.

The community health units served by the selected health facilities were included in the household cluster sample survey to measure health outcomes. We followed the procedures and sample size estimates of the World Health Organization (WHO) method for assessing immunization coverage [8,9]. Thus, we had a sample size of 30 clusters of 10 households, each with children under five for a total of 300 households in each community health unit.

For qualitative data, we used purposive sampling to select respondents who had been engaged in the CBHIS: officers in charge of health facilities, chairmen of community health committees, and community health workers. We aimed to select a total of 24 key informants and 8-12 participants for 12 focus groups (2 per study district). These were pre-determined numbers, considered adequate to achieve data saturation as described by Miles et al. [8,9].

Data Collection

Trained enumerators collected both quantitative and qualitative data using pretested tools from consenting respondents. All tools included assessment of the use of the CBHIS and local health information system.

Quantitative Data

Our health facility tool contained items that assessed the performance of governance, measured by the number of meetings (confirmed by minutes), awareness of the functions of the committee, community representation and use of available data displayed on the chalkboard. The tool also assessed management performance measured by use of data to track progress, make informed decisions, and feed into periodic plans. Service delivery was assessed using a client satisfaction exit interview tool administered to patients after they received services at the facility. Participants rated their level of satisfaction with staff attitudes, staff availability, and availability of prescribed medicines on a 4-point scale (poor, fair, good or excellent), while waiting time was rated on a 3-point scale (less than 1 hour, 1 hour to 2 hours, or more than 2 hours). They were asked to rate the use and importance of mother and child health book and clinic card for information sharing.

We collected household data using a structured questionnaire that was administered to household heads or their representatives. Data collected included health seeking behavior, environmental health, CHW visits and exchange of health information. Data collected were checked by supervisors and validated by research assistants who re-visited and collected data from a randomly selected 10% of households. Data were cleaned by research assistants under the supervision of co-investigators.

Qualitative Data

We collected qualitative data from purposively selected knowledge rich individuals using interview guides to obtain information from community leaders, service providers, health managers, CHWs and community members on the views and perspectives on health services and their roles as well as levels of involvement. In addition, consumers were asked about their engagement with the health information system and the health environment, to gain insight into the views of individual consumers in relation to information shared between different groups regarding health issues, and specific learning attributable to engagement with the health system.

We documented and taped qualitative interviews. Recordings were then transcribed into text. Two interviewers managed each focused group discussion so that one conducted the interview freely while the second taped the conversation as well as took notes. These field notes also captured non-verbal information.

Data Analysis

The quantitative data were entered by data entry clerks; 10% of questionnaires were re-entered by independent research assistants for validation purposes. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and cross-tabulations to compare the coverage rates between intervention and control sites. The significance of prepost differences was tested by the Chi-square statistic using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 16. Client satisfactions exit interviews were analyzed by collapsing the ratings into two categories of responses (poor and fair, versus good and excellent). Waiting time responses were categorized as 2 hours or less versus more than 2 hours. We used chi-square statistics to compare client’s responses re satisfaction and waiting times between intervention and non-intervention districts.

In the analysis we cross tabulated information utilization practice by level and type of respondent as well as health outcomes comparing intervention and non-intervention districts. Qualitative data were transcribed and then coded using a deductively developed coding framework. The data were then isolated and clustered into common patterns, themes and subthemes. We synthesized data into coherent groups of similar statements as described by Miles and Huberman [8]. Quotes of what the participants said word-for word were inserted to illustrate specific patterns emerging from the data with a particular focus on themes and sub themes relevant to information sharing and usage.

RESULTS

Opportunities for Iterative Bidirectional Information Sharing

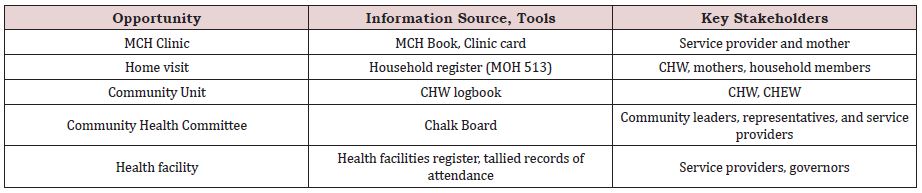

The study respondents, which included clients, health service providers, managers and governors identified five opportunities for iterative bidirectional information sharing, explaining how they facilitated discussions between the health workers and consumers using available information in Table 1.

Mother and Child Health (MCH) Book or Card

Service consumers identified MCH book or card as a source of information and clinic visit as an opportunity for dialogue at the health facility and the household. Mothers said that health providers used the information to explain their own or their children’s health situation. Further, the mothers used it to monitor their antenatal care and immunization schedules. The MCH book reminded them of their due dates for the clinics. Reading the book enabled them to monitor their children’s growth and guided their feeding based on the trends of weight for age curves. A mother in Kisumu district said “MCH book reminds me of the immunization dates and am able to see the baby’s growth by looking at the graph on how the baby is growing”. Respondents also indicated that data from the MCH book was used in dialogue with CHWs during household visits, and health providers during clinic visits clinic. This dialogue helped them jointly decide on action to improve their health and that of their children.

Household Register

Respondents reported that household registers enabled the households to measure their health status. It created a chance for them to have dialogue with CHWs on health actions using information contained in the registers. Through dialogue between the households and the CHWs they were able to identify gaps in health status and decide on timely actions to improve the use available essential health services. Respondents described the household register as providing a comprehensive view of health status in the community. A CHW discussant explained “It gives a snapshot status of well-being of a household: demographic, environmental, service coverage, morbidity, mortality, and food security”.

CHW Logbook

Respondents explained that the logbook provided data on events at the household level encountered by the CHWs. It captured data on current morbidity and mortality, data on compliance with medication for chronic illnesses and thus facilitated defaulter tracing. CHWs described the book as a tool they used to when reporting to CHEWs who were their supervisors. Thus, data in the logbook, helped facilitate two-way discussions between the CHEWs and CHWs. It also provided surveillance data that was critical for understanding health trends in the community and strengthened referral mechanisms to enhance access to care, particularly for vulnerable mothers and children. One CHEW remarked “the logbook is the tool that enables me to assess the effort being made by the CHW and is a basis for output-based rewards”

The Chalkboard

Respondents, both health providers and consumers, described the chalkboard as a tool for community level dialogue. Centrally placed in the community, it provided comprehensive community diagnosis and triggered discussion, leading to decisions at individual and community levels for critical actions for health improvement. A village Chief commented. “Repeated reading of the information on the chalk board by community members and discussion, decisions and actions over a period of time leads to improved health practices, helping the community to appreciate their progress”

Health care providers and community leaders described the benefits of the dialogue days they held to discuss information contained on chalkboards. The dialogue days provided all stakeholders an opportunity to plan and act at individual, group, community and health systems levels. “We have found it very useful; over time, we have learnt the skills to collect and analyze data. We also use this data for discussion with other partners” said a community leader during a key informant interview. Health workers and community leaders felt that dialogue days had helped to drive the health improvement initiative.

The Health Facility Register

The respondents described clinic level dialogue, based on coverage levels reported either on the chalkboards or on the health facility charts. Educators selected dialogue topics from these datasets and the trends curves to demonstrate the magnitude of issues needing action. A health worker in an in-depth interview explained “…the health facility register provides a quick picture of defaulters or non-users that can challenge the CHWs, CHEWs, Community Health Committee members and thus place clear responsibility on community representatives to ensure that their members access care”. A committee member added “the modified health facility register demonstrates types of illness occurring in villages and can help us know emerging health problems that should be addressed”.

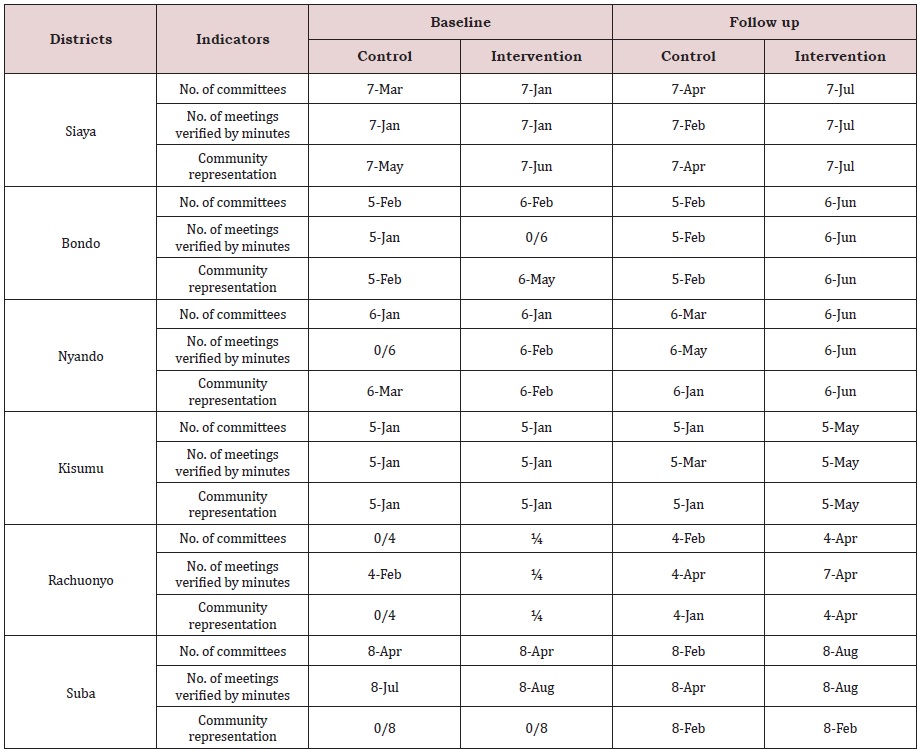

Governance and Management

Health facility management boards and committees were in place in all the health facilities assessed. However some boards and committees that were not active at baseline assessment become more active at post-intervention assessment, with intervention sites showing statistically greater improvements than control sites (Table 2). The governing and management structures at the district level had poor relationships at baseline, but these relationships had markedly improved post-intervention. Respondents felt that the representativeness and inclusiveness of the boards and committees had improved post-intervention, due to better customer and gender representation. Members also knew their constituencies better and roles better. According to respondents, the structures had improved in the use of documented information in decision-making.

At baseline, the functions of the District Health Management Teams (DHMT) and Hospital Management Teams were unclear to the respondents from the Health Center Management and the Dispensary Management Teams. However, survey results indicate that there was a more comprehensive knowledge of their functions post-intervention.

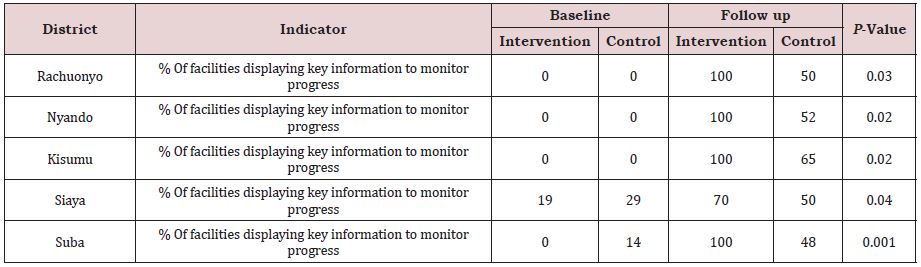

Concerning management, about half of the study health facilities had annual health plans at the baseline assessment, but at post-intervention assessment all the health facilities had annual plans, with greater improvement at intervention sites. The health management information system generated from the facilities the key source of information available for planning in the district, at baseline. Post-intervention, CBHIS became more available. Thus, those developing district level plans were better able to use information from Health Facility Information System and CBHIS. However, capacity for data management did not change much during the research period. Only the district offices had computers and personnel for data management. Those working at other health system levels recorded their data in books and registers, and prepared reports from them. All intervention districts registered improvements in data management practices. Feedback was given after every data collection period. The information was displayed in charts and diagrams in the health facilities and was used for planning and informed action (Table 3).

Service Delivery and Health Outcomes

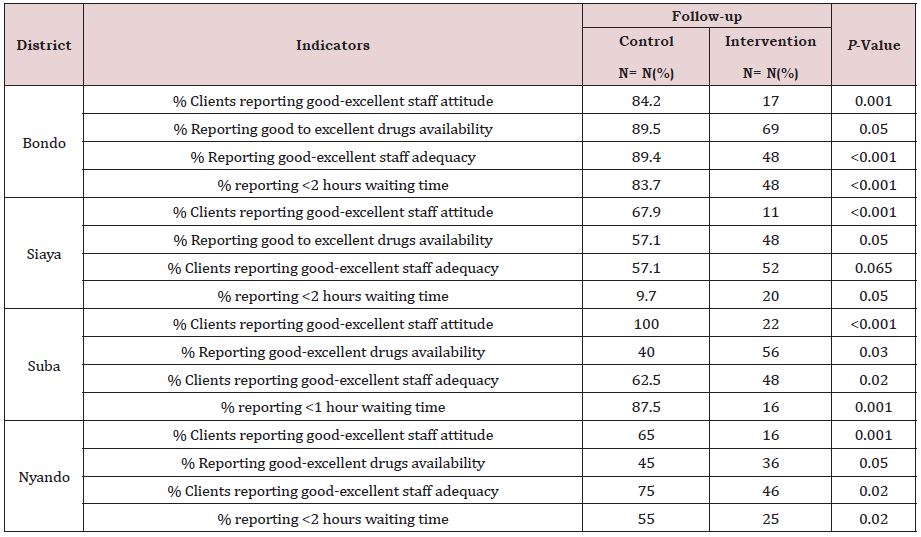

Client satisfaction, particularly staff friendliness, improved more at the intervention than control sites post-intervention (Table 4). At the Bondo and Rachuonyo intervention districts, clients reported a higher level of satisfaction than clients at control sites, post-intervention. Nyando facilities registered better drug availability and waiting time at intervention sites. Kisumu district recorded the biggest difference between intervention and control sites in clients’ satisfaction.

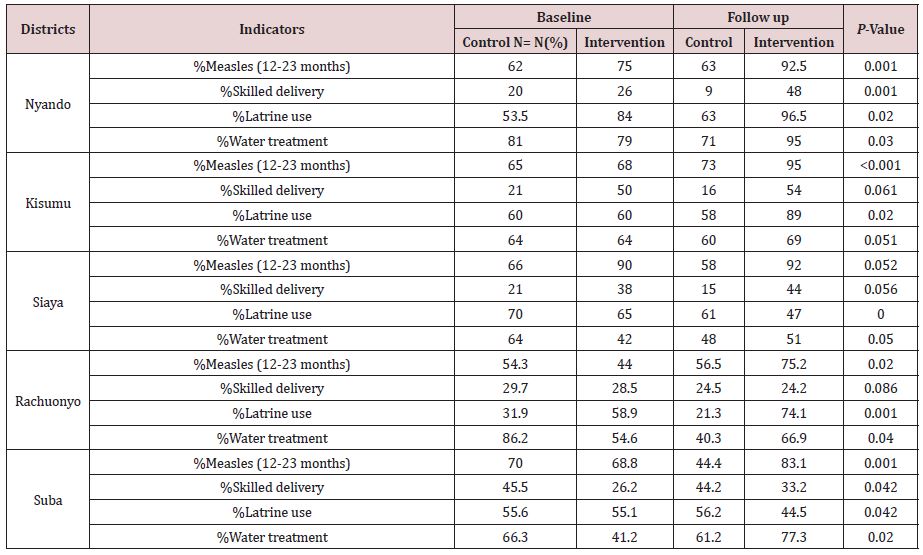

There were significantly better improvements in immunization coverage (12-23 months), skilled delivery, latrine use, and water treatment, in intervention sites than in control sites (P<0.05; Table 5). In Nyando District skilled delivery almost doubled between preand post-data collection periods.

DISCUSSION

This study identified five opportunities and tools for bidirectional information sharing. MCH books or cards provided valuable information to be discussed between providers and consumers, contributing to timely evidence-based decisions and actions. Other tools, described as helping to create a communication interface between providers and consumers, included household registers, chalkboards, and health facility registers. Health facility management committees provided opportunities for dialogue between service providers and consumers; Community Health Committees provided dialogue opportunities to health service representatives, communities, and CHWs; and households provided dialogue opportunities to caregivers and CHWs and CHEWs. The clinic was a major dialogue hub where all stakeholders converged from time to time. These tools and formal structures for bidirectional information sharing were set up at all health care system levels within the districts and included both professional and non-professional health care providers. Enhanced bidirectional dialogues yielded improvements in governance, management, service delivery, and health outcomes. These findings are consistent with those reported in participatory action research studies that have also aimed to engage community members in solution-oriented dialogue [10].

Bridging the interface between the household and the health system was considered key by Kenyan Health Sector Strategic Plan II [7]. Our findings indicate that bidirectional engagement between providers and consumers empowers both by making them learners and facilitators in the health status improvement process [11]. Information-empowered consumers are able to take charge, monitor their babies’ growth and their households’ health status, and thus take appropriate action to address gaps identified through dialogue with the CHW at household, and with service providers at the health facility. Further, consumers have space to voice their concerns, prioritize their issues, and engage with different stakeholders in actions for improvement. The findings demonstrate how local people analyze their own conditions, as presented on chalkboards, by choosing their own means of improving them and utilizing information as a tool for change, as supported by other workers [12,13]. Local people sharing, owning and using information improves their self-esteem, confidence, and increases their motivation and commitment to the health improvement process [14].

Mouton asserts that a participatory approach to information systems is a process of involvement for change [14]. He argues that this approach mobilizes people to use their local knowledge in action for improvement, which underpins the effectiveness of iterative bidirectional dialogue. The empowering dialogue also occurs within the service system itself, between providers, managers, and policy makers, as opportunities for two-way sharing are exploited throughout the health system. This is equally important in bidirectional conversations between researchers on the one hand and practitioners, managers, policy makers and consumers on the other, using platforms such as communities dialogue days, facility committee meetings and policy dialogue sessions.

The approach contributed to improved indicators such as immunization coverage, water, and sanitation. Skilled delivery is the indicator that improved the least, perhaps due to complexities on both supply and demand sides requiring more time to change. Dialogue and action with local communities is more likely to yield positive results than the health service providers working on their own, but only if the services are available such as is the case with immunization [15].

The application of information to drives positive change has been demonstrated [16], and to deliver cost savings, [2], yet this is a sustainable model based on quality data generated by volunteers [4,17].

The CBHIS model contributed to improving governance, management, and service delivery. Other researchers have demonstrated the effectiveness of information in improving the performance of governing and management structures [18,19], as well as the markedly improved the quality and sustainability of health initiatives.

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

This study has some limitations. Although the study was quasiexperimental in design, the intervention period was rather short for expected changes in the health system, because of the complexity of the context. Further, the study was limited to the lakeshore districts, which have unique characteristics. This makes the generalizability of the findings and applicability of the model limited to similar settings. Having intervention and control sites in the same district may have influenced improvement in control sites as well, seen in some findings such as client’s satisfaction. Lastly the CBHC consists of several components and CBHIS is only one of them. Isolating the changes attributable only to the information system is not possible.

The study results may not be generalizable to other parts of Kenya due to contextual, social or cultural settings experienced by different communities. Factors affecting reliability and validity, such as heterogeneity of the group being studied, age, educational background, etc., may vary due to inherent differences in communities,

CONCLUSION

CBHIS provides opportunities for bi-directional information mechanisms that can be used for health systems performance improvement in health services at the community level. Engagement of providers and consumers in using available information for dialogue, decision-making, planning, and action, improves data ownership, usage, and the performance of the health system.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study involved human beings and was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki ethics guidelines and was approved by Great Lakes University Research Ethical Review Board and National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI). All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the research study. The study protocols and consent forms were reviewed and approved by Great Lakes University of Kisumu Ethical Review Board. The national research clearance certificate and permit was obtained from National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by Tropical Institute of Community Health department of research and development.

REFERENCES

- Alliance for health policy and system research: Neglected health systems research: Health information systems Geneva.

- Don DS, Harun K, Conrad M, Graham R (2004) In focus: fixing health systems.

- Christine F, Cordaid AJ (2007) Health programme information systems as a pool for organizational development. The Hague: International institute for Communication and Development.

- Careena O, Dan K (2014) Validity and reliability of data collected by community health workers in rural and peri-urban contexts in Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res 14(1): S5.

- Kenya Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation (2007), Community Health Strategy implementation Guidelines.

- Kaseje DCO, Olayo RN, Wafula CO, Muga RO (2010) The impact of community dialogue in improving the performance of the District Heath Systems. Global Public Health Journal.

- Kenya ministry of public health and sanitation reversing the trends (200) The Second National Health Sector Strategic Plan (NHSSP II) 2005-2010 MOPHS.

- Miles MB. Huberman AM (1994) Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook of new methods. Sage, Beverly Hills, USA.

- Stanley L, David R (1985) Surveys to measure programme coverage and impact: a review of the methodology used by the expanded programme on immunization. World Health Stat Q 38(1): 65-75.

- Robert C (1994) Participatory rural appraisal (PRA): Analysis of experience. World Development 22(9): 1253-1268.

- Keartland, Liselle (1997) The evaluation of development effectiveness, in participatory development management and the RDP. In: Liebenberg S, Stewart P (Eds.), Juta, Kenwyn, England.

- Botha N, Treurnicht S (1999) Participatory learning and action: Challenges for south africa. Africanus 29(1).

- Nicole M, Tony B, Etienne N, Kate R (1999) Empowerment for development: Taking participatory appraisal further in rural South Africa. Development in Practice 9(3): 261-273.

- Johann M (1989) Participatory research: A new paradigm for development studies. In: Development is for People, Coetzee JK (Ed.), Halfway House, Southern Book Publishers, South Africa.

- Carla AZ, Ties B (2005) Health information systems: the foundations of public health. Bull World Health Organ 83(8): 578-583.

- Robert C (1983) Rural development: Putting the last first. Harlow Longman London, UK.

- Srinvasan S, O’Fallon L, Dearry A (2003) Creating healthy communities, healthy homes, and healthy people: initiating a research agenda on the built environment and public health. Am J Public Health 93(9): 1446- 1450.

- Otieno C, Kaseje D, Ochieng B, Githae M (2012) Reliability of community health worker collected data for planning and policy in a peri-urban area of Kisumu, Kenya. Journal of Community Health 37(1): 48-53.

- Mikaya E, Sohani S, Barasa M, Kaseje M, Nyawa R (2003) Community Participation in promoting sustainable quality of Health Care within the District Health System. TICH Publication Nairobi, Kenya, ISBN 9966- 9796–0–3.

Article Type

Research Article

Publication history

Received Date: November 10, 2021

Published: November 23, 2021

Address for correspondence

Beverly M Ochieng, Tropical Institute of Community Health, P.O Box 2224-40100, Kisumu, Kenya

Copyright

©2021 Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science, All rights reserved. No part of this content may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means as per the standard guidelines of fair use. Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

How to cite this article

Beverly MO, Dan COK. Perspectives on an Iterative and Bidirectional Information System and its Role in Improving Health Outcomes in Western Kenya. 2021- 3(6) OAJBS.ID.000350.

Figure 1: CBHIS Dialogue model for health improvement.

Table 1: Opportunities for bidirectional information sharing by sources and stakeholders.

Table 2: Number of community health units with functioning committees by districts, interventions, and controls.

Table 3: Percent of Health facilities displaying and using analyzed data to monitor progress district.

Table 4: Service delivery, clients’ satisfaction, post intervention.

Table 5: Selected outcomes by district and intervention status.