Neuraxial Anesthesia in Pregnant Women

ABSTRACT

Background: Neuraxial anaesthesia and analgesia techniques include spinal, epidural, and combined spinal-epidural. Neuraxial

anesthesia (NA) is most commonly used for surgery of the lower abdomen and lower extremities. Neuraxial analgesia plays an

important role in pregnant women. Neuraxial analgesia is recommended for childbirth to reduce sleep deprivation and stress and

dehydration induced by labour pain.

Methodology: A systematic review was carried out through various databases from January 2020 to October 2022; The search

and selection of articles was carried out in indexed journals in English.

Results: Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, interest in neuraxial anesthesia has increased considerably among pregnant women.

Neuraxial anesthesia should be considered the preferred anaesthetic method in pregnant women because it helps to mitigate

difficult intubation, presents fewer complications associated with general anesthesia, among other reasons.

Conclusion: This review offers updated and detailed information on the current guidelines for neuraxial anesthesia in different

clinical contexts, whether in the context of COVID-19, epilepsy and multiple sclerosis, among others, in order to provide better care

and focus for pregnant women.

KEYWORDS

Anesthesia; Neuroaxial; Pregnant women; COVID-19

INTRODUCTION

Neuraxial anesthesia and analgesia techniques include spinal, epidural, and combined spinal-epidural. Neuraxial anesthesia is performed by placing a needle between the vertebrae and injecting medication into the epidural space (for epidural anesthesia) or the subarachnoid space (for spinal anesthesia); [1]. Neuraxial anesthesia (NA) is most commonly used for surgery of the lower abdomen and lower extremities. The sensory level required for a specific surgery is determined by the dermatome level of the skin incision and by the level required for surgical manipulation; these two requirements can be very different. As an example, a lower abdominal incision for caesarean delivery is made at the T11 to T12 dermatome, but a T4 spinal level is required to avoid pain with peritoneal manipulation [2,3].

The development of regional anesthesia began with the isolation of local anaesthetics, the first being cocaine (the only natural local anesthetic). The first regional anesthesia technique performed was spinal anesthesia, and the first operation under spinal anesthesia was in 1898 in Germany by August Bier. Prior to this, the only local anesthetic techniques were topical anesthesia of the eye and infiltration anesthesia [4]. The central nervous system (CNS) comprises the brain and spinal cord. The term neuraxial anesthesia refers to the placement of local anesthesia in or around the CNS [5].

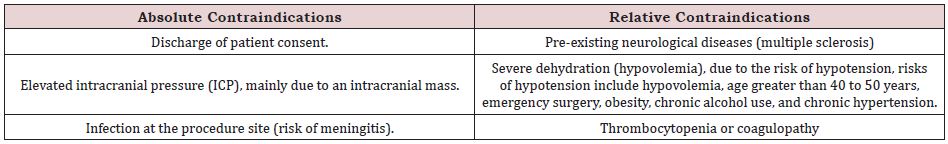

Neuraxial anesthesia is used as the sole anaesthetic or in combination with general anesthesia for most procedures below the neck. There must be advice to the patient about the procedure, and signed informed consent is necessary [6]. Since the procedure is usually performed in awake or lightly sedated patients, the indication for spinal anesthesia and what to expect during neuraxial placement, risks, benefits, and alternative procedures are some of the discussions that can help calm anxiety. Table 1 shows the main absolute and relative contraindications for neuraxial anesthesia (spinal and epidural); [7,8].

Neuraxial analgesia plays an important role in pregnant women. Neuraxial analgesia is recommended for childbirth to reduce sleep deprivation and stress and dehydration induced by labour pain [9]. Although many authors do not recommend them in certain types of patients, such as Multiple Sclerosis, since it has been suggested in the past that neuraxial techniques, specifically spinal anesthesia, may contribute to increasing relapses after childbirth. because the demyelinated spinal cord is exposed to neurotoxic local anesthetic agents [10]. Although to date it is known that neuraxial anesthesia is not contraindicated in patients with multiple sclerosis. Due to this, we want to provide updated and accurate information on current guidelines in different clinical contexts, whether in the context of COVID-19, epilepsy and multiple sclerosis, among others, in order to provide better care and focus for pregnant women.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A systematic review was carried out, the main databases used are PubMed, SciElo and ScienceDirect. Articles indexed in Englishlanguage journals were selected. As keywords we find the terms: Anesthesia; Neuroaxial; pregnant; COVID-19. In this review, 98 original and review publications related to the subject studied were identified, of which 30 articles met the specified inclusion requirements, such as articles that were in a range of not less than the year 2020, that were articles from full text and that reported on neuraxial anesthesia in pregnant women, and associated with different clinical contexts. As exclusion criteria, it was taken into account that the articles did not have sufficient information and that they did not present the full text at the time of their review.

RESULTS

Obstetric Anesthesia Guidelines

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, interest in neuraxial anesthesia has increased considerably among pregnant women. In order to avoid general anesthesia and the risks that it brings both for the patient and for the health personnel who attend her [11]. Obstetric anesthesia guidelines have not changed significantly since the first pragmatic clinical recommendations published in spring 2020 [12]. Overall, 2 areas of concern about the safety of neuraxial anesthesia in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients were raised after initial reports from China: maternal hypotension during caesarean delivery and thrombocytopenia prohibiting the safe neuraxial procedure, as either epidural, combined spinal-epidural or spinal anesthesia [13].

Alerts about possible hemodynamic instability after neuraxial anesthesia for caesarean delivery seemed unfounded with the current practice of preventing spinal hypotension with vasopressors (phenylephrine infusions), and any potential concerns were quickly allayed [14]. In healthy pregnant patients with a normal platelet count during pregnancy that rules out gestational or idiopathic thrombocytopenia, it is not necessary to wait for an additional platelet count on admission to administer neuraxial analgesia during labour [15,16] with a diagnosis of preeclampsia with or without severe features, obtaining a platelet count prior to a neuraxial procedure (neuraxial labour analgesia or spinal anesthesia for caesarean delivery) is still indicated, with the acceptable cut-off point of 70,000 in the absence of any coagulopathy [17,18].

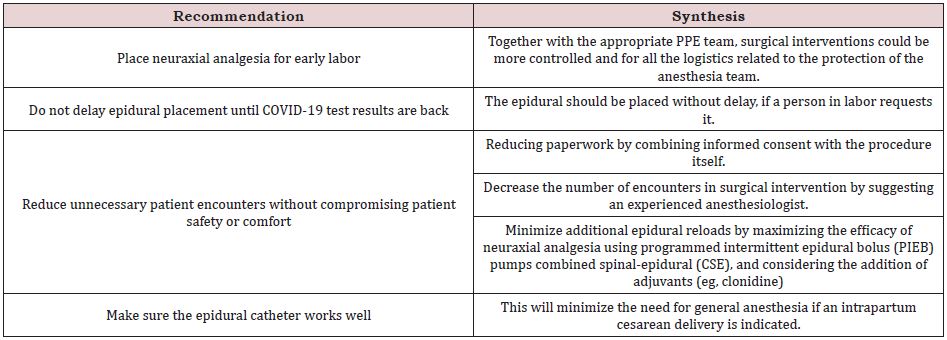

Recommendations for Neuroaxial Analgesia

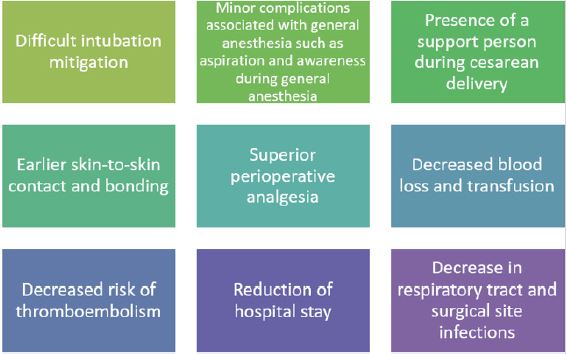

These recommendations originated mainly from the lessons of US institutions that shared their first experiences in mid-March 2020. In Table 2 we can identify the pillar of recommendations that still need to be implemented . The provision of neuraxial anesthesia via an indwelling epidural catheter for an intrapartum caesarean delivery or with a spinal or combined spinal-epidural is unequivocally the preferred method to avoid aerosolization of viral particles during endotracheal intubation and extubating and other circumstances resulting in airway manipulation [20]. As has already been reported in different studies, we can find many reasons why neuraxial anesthesia should be considered, as the preferred anesthetic method in most pregnant women, which we can identify in Figure 1; [21-23]. A maternal history of epilepsy should not dictate the mode of delivery. Neuraxial analgesia for labour is recommended to reduce sleep deprivation and labour pain-induced stress and dehydration.

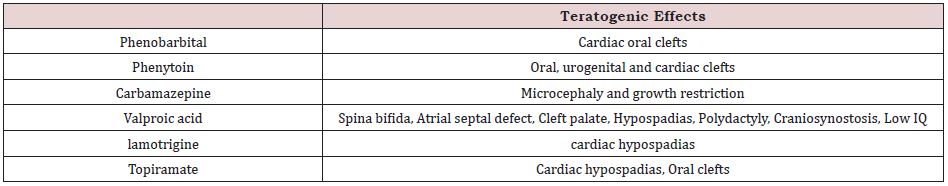

Epilepsy and Multiple Sclerosis in Pregnant Women vs Neuroaxial Anesthesia

Epilepsy is the most common serious neurological disorder in pregnant women with an estimated global incidence of 6.85 per 1000 women [24]. Early input from an epilepsy specialist is extremely valuable, as drug choice and dosage may need to be modified during pregnancy. In Table 3 we can identify the main antiepileptic drugs that have been associated with teratogenic effects if the correct dose is not established and there is no proper control of it. In conclusion, a maternal history of epilepsy should not dictate the type of delivery. Neuraxial analgesia for labour is recommended to reduce sleep deprivation and labour pain-induced stress and dehydration. If opioids are used, pethidine should be avoided due to its epileptogenic potential. All general anesthetic drugs are acceptable for use in epileptic women, except etomidate, which may lower the seizure threshold in susceptible individuals [25,26]. Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an immune-mediated chronic demyelinating disorder of the central nervous system (CNS) with an immune-mediated aetiology. It is three times more common in women; the median age at diagnosis is 30 years [27]. It has been suggested in the past that neuraxial techniques, specifically spinal anesthesia, may contribute to increased relapses after delivery because the demyelinated spinal cord is exposed to neurotoxic local anesthetic agents. However, the Pregnancy in Multiple Sclerosis (PRIMS) study found no correlation between the use of neuraxial techniques and relapses of multiple sclerosis in the puerperium. Therefore, neuraxial anesthesia is not contraindicated in patients with multiple sclerosis [28].

DISCUSSION

To date it has been challenging to report management and clinical outcomes in critically ill obstetric patients. Reports on anesthetic management and the use of intensive care in pregnant women according to different pathologies are still scarce. But great efforts have been made to be able to have good and correct anesthetic approaches in pregnant women. The retrospective descriptive cohort study conducted by Luis et al., in which they describe the clinical characteristics and frequency of maternalfoetal and neonatal complications according to the neuraxial anesthesia technique in women diagnosed with twin-twin transfusion syndrome, reported that anesthesia probably neuraxial (epidural, spinal) is associated with similar maternal hemodynamic variables at the time of surgery, but a clear conclusion has not yet been reached, since prospective studies are still needed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the different neuraxial anesthesia techniques in patients with this pathology [29].

In times of the COVID-19 pandemic, neuraxial block was the recommended modality of analgesia and anesthesia in pregnant women. The retrospective cross-sectional case-control study by Sangroula et al. [30] compares the hemodynamic changes associated with neuraxial block in pregnant women positive for COVID-19. We conclude that the incidence and severity of hypotension after neuraxial blocks were similar between COVID-19 positive and COVID-19 negative pregnant women. But it was found that the most important risk factor for hypotension in this case was a BMI>30. This demonstrates the safety of neuraxial anesthesia, as opposed to patients with additional risk factors or complications during pregnancy [30].

Although these studies report the side effects of neuraxial anesthesia in different clinical settings, they are still inconclusive in reporting the safety in a general setting of neuraxial anesthesia according to different underlying pathologies or risk factors. A strength of the current study is the methodology implemented, regarding the literature search, and steps in the selection of relevant articles, quality assessment, and data extraction. However, this study has several limitations, which should be taken into account before reaching a conclusion, among these are the little evidence from the analysis of clinical trials that demonstrate the safety of neuraxial anesthesia according to different pathological areas of the pregnant woman, Therefore, more studies are needed to answer these questions.

CONCLUSION

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, interest in neuraxial anesthesia has increased considerably among pregnant women. In Table 3 we can identify the pillars of recommendation of neuraxial analgesia in pregnant women. Neuraxial anesthesia should be considered the preferred anesthetic method in pregnant women because it helps to mitigate difficult intubation, presents fewer complications associated with general anesthesia such as aspiration and awareness during general anesthesia, among other reasons shown in Figure 1.

REFERENCES

- Abdulquadri MO, Joe MD (2022) Spinal Anesthesia. StatPearls Publishihing, Florida, USA.

- Plewa MC, McAllister RK (2022) Postdural Puncture Headache. StatPearls Publishing, Florida, USA.

- Kadir RA, Kobayashi T, Iba T (2020) COVID-19 coagulopathy in pregnancy: critical review, preliminary recommendations, and ISTH registry-Communication from the ISTH SSC for Women’s Health. J Thromb Haemost 18(11): 3086-3098.

- Le Gouez A, Vivanti AJ, Benhamou D (2020) Thrombocytopenia in pregnant patients with mild COVID-19. Int J Obstet Anesth 44: 13-15.

- Breslin N, Baptiste C, Gyamfi-Bannerman C (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019 infection among asymptomatic and symptomatic pregnant women: two weeks of confirmed presentations to an affiliated pair of New York City hospitals. MFM 2(2): 100118.

- Breslin N, Baptiste C, Miller R (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: early lessons. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 15: 376-383.

- Prabhu M, Cagino K, Matthews KC (2020) Pregnancy and postpartum outcomes in a universally tested population for SARS-CoV-2 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. BJOG 127(12): 1548-1556.

- Allotey J, Stallings E, Bonet M (2020) Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 370: 3320.

- (2021) Update to living systematic review on COVID-19 in pregnancy. BMJ 372: n615.

- DeBolt CA, Bianco A, Limaye MA (2021) Pregnant women with severe or critical coronavirus disease 2019 have increased composite morbidity compared with nonpregnant matched controls. Am J Obstet Gynecol 224: e511- e512.

- Ellington S, Strid P, Tong VT (2021) Characteristics of women of reproductive age with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by pregnancy status-United States, January 22-June 7, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 69: 769-775.

- Villar J, Ariff S, Gunier RB (2021) Maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality among pregnant women with and without COVID-19 infection: the INTERCOVID multinational cohort study. JAMA Pediatr 175:817- 826.

- Villar J, Gunier RB, Papageorghiou AT (2021) Further observations on pregnancy complications and COVID-19 infection-reply. JAMA Pediatr 175:1185 - 1186.

- (2019) CDC: Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Pregnancy-related Deaths- United States, 2007-2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 68(35) 762-765.

- Gur RE, White LK, Waller R (2020) The disproportionate burden of the COVID-19 pandemic among pregnant black women. Psychiatry Res 293: 113475.

- Holness NA, Barfield L, Burns VL (2020) Pregnancy and postpartum challenges during COVID-19 for African-African women. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc 31:15-24.

- (2019) Society for maternal-fetal medicine management considerations for pregnant patients with COVID-19.

- Martinez R, Bernstein K, Ring L (2021) Critical obstetric patients during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: operationalizing an obstetric intensive care unit. Anesth Analg 132: 46-51.

- Pourdowlat G, Mikaeilvand A, Eftekhariyazdi M (2020) Prone-position ventilation in a pregnant woman with severe COVID-19 infection associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Tanaffos 19: 152- 155.

- Toclcher MC, McKinney JR, Eppes CS (2020) Prone positioning for pregnant women with hypoxemia due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Obstet Gynecol 136: 259-261.

- Barrantes JH, Ortoleva J, O’Neil ER (2021) Successful treatment of pregnant and postpartum women with severe COVID-19 associated acute respiratory distress syndrome with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. ASAIO J 67: 132-136.

- Hou L, Li M, Guo K (2021) First successful treatment of a COVID-19 pregnant woman with severe ARDS by combining early mechanical ventilation and ECMO. Heart Lung 50(1): 33-36.

- Larson SB, Watson SN, Eberlein M (2021) Survival of pregnant coronavirus patient on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Ann Thorac Surg 111(3): e151-e152.

- Rushakoff JA, Polyak A, Caron J (2021) A case of a pregnant patient with COVID-19 infection treated with emergency c-section and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Card Surg 36(8): 2982-2985.

- Takayama W, Endo A, Yoshii J (2020) Severe COVID-19 pneumonia in a 30-year-old woman in the 36th week of pregnancy treated with postpartum extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Am J Case Rep 28(21): e927521.

- Katz D, Bateman BT, Kjaer K (2021) The Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology (SOAP) COVID-19 Registry: an analysis of outcomes among pregnant women delivering during the initial SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in the United States. Anesth Analg 133(2): 462-473.

- Grunebaum A, McCullough LB, Litvak A (2021) Inclusion of pregnant individuals among priority populations for coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination for all 50 states in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol 224(5): 536-539.

- Razzaghi H, Meghani M, Pingali C (2021) COVID-19 vaccination coverage among pregnant women during pregnancy-eight integrated health care organizations, United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 70(24): 895-899.

- Luis L, Laura Z, Akemi S, Natalia SP, Leidy LE, Elinar BV, Yuliana OP (2021) Safety of neuraxial anesthesia in patients twin pregnancy and twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome taken to laser photocoagulation. Retrospective cohort study. Rev Colomb Obstet Ginecol 72(3): 258-270.

- Sangroula D, Maggard B, Abdelhaleem A, Furmanek S, Clemons V (2022) Hemodynamic changes associated with neuraxial anesthesia in pregnant women with covid 19 disease: a retrospective case-control study. BMC Anesthesiol 22(1): 179.

Article Type

Research Article

Publication history

Received Date: December 06, 2022

Published: February 20, 2023

Address for correspondence

Erika Nataly Buitrago Hernández, Anesthesiology Resident, Universidad Militar Nueva Granada, Colombia

Copyright

©2022 Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science, All rights reserved. No part of this content may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means as per the standard guidelines of fair use. Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

How to cite this article

Erika Nataly BH, Juan Pablo GM, Ariel HA, Diana Marcela AA, Andrés Felipe MP, et. al. Neuraxial Anesthesia in Pregnant Women. 2023- 5(1) OAJBS.ID.000547.