Massive Pulmonary Embolism in Pregnancy and Perimortum Caesrean Section

ABSTRACT

In pregnancy, the incidence of pulmonary embolism (PE) is increased fivefold when compared to nonpregnant women of the same age, and PE is one of the leading causes of death during pregnancy. However, the diagnosis of PE among pregnant women is complicated by concerns regarding radiation exposure. We report the case of a 33-year-old woman G4P3 at 38+3 weeks gestation with an acute PE that required Perimortem Caesarian section, CPR of the mother followed by Thrombolysis for massive Pulmonary Embolism.

CASE STUDY

33-year-old woman, non-English speaker BMI of 35, at 38+3 weeks gestation presented to Labor Ward of a busy Tertiary Care hospital via ambulance. She woke up at 5am with not feeling well. She collapsed in the labor ward went unresponsive, and cardiac arrest team was called. She had no history of prior cardiovascular disease.

On examination she was in sinus rhythm with a pulse rate of 125pm, her oxygen saturation was 60% on non-rebreather mask and she was hypertensive. But conversely was cool, peripherally shut down, with mottled skin. Her best GCS was 10/15, but this was fluctuant. Unable to assess FH via CTG but confirmed presence on USS.In-out catheter showed negative proteinuria.

Differential Diagnoses were made including Severe preeclampsia/ eclampsia, Massive pulmonary embolism, Intracranial haemorrhage, Covid-19 – related. Airway was secured immediately on labour ward as there was insufficient improvement in oxygenation with c-circuit shifted to Theatre for Emergency LSCS and Loaded with 4g MgS04. Delivery of live female infant – APGAR scores of 9 and 10. However, within seconds of delivery there was a sharp drop in CO2, her pulse was impalpable and went into a PEA arrest. CPR commenced immediately.

Hemodynamic stability was achieved with vasopressors and the LSCS was completed promptly with both consultant obstetrician and anaesthetist’s involvement. However, despite adequate hemodynamic, we continued to have significant difficulty in maintaining saturations. Her end-tidal CO2 was also unexpectedly low (2.5-30).

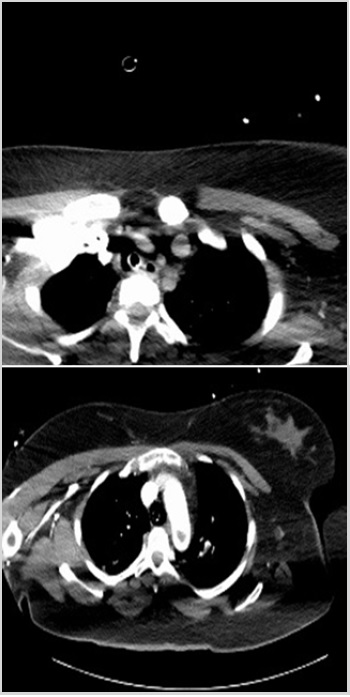

Given the obvious ventilation-perfusion mismatch with normal peak pressures we were somewhat convinced that this was likely to be a pulmonary embolism. Decision was made to transfer to CT and CT PA was performed which showed bilateral pulmonary emboli with a large thrombus in the arch of the aorta with extension into the left subclavian and left common carotid arteries. CT noncontrast of her brain also revealed signs of a developing left MCA infarct. There was no suspicion of an aortic dissection.

At this point the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit where Thrombolysis was instituted immediately. It was discussed as an MDT with obstetric, anaesthetic, hematologic and medical input. It was agreed unanimously that we would accept the risk of bleeding in favour of the benefit of the improvement of ventilation/potential further arrests. Following Thrombolysis patient developed massive PPH. Massive transfusion protocol activated (Packs I and II). Uterotonics Oxytocin bolus and 40 units infusion, Carboprost 3 doses Misoprostol 1g Tranexamic acid 1g and Bakri balloon insertion. After 6 hours after delivery Patient was still sedated, intubated, and ventilated in ICU. TTE performed at the bedside was difficult due to body habitus, but clearly hyperdynamic circulation. Further MDT discussion including vascular surgery and interventional radiology regarding next steps-agreed that transfer to specialist centre was appropriate. ICU to ICU transfer was arranged.

Patient continued on heparin infusion, largely supportive and conservative management. No further episodes of destabilisation or requirement for thrombectomy. Right sided deficit-further imaging confirmed an established left MCA infarct. TOE performed at the bedside-showed a patent foramen ovale, which explained the presence of thrombi in both central venous and arterial systems. Despite this, she was following commands and was extubated on Day 2. Excluding pregnancy, there were no other significant risk factors for the development of VTE.Shortly after discharge from ICU -repatriated to stroke ward for rehabilitation (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

Clinically PE is characterized by dyspnoea, tachycardia, sudden chest pain and shock. Cyanosis may occur in cases of massive PE. The predisposing factors include increased coagulopathy, immobilization, trauma to blood vessels and pregnancy. However, the diagnosis of PE is often difficult and sometimes missed, leading to higher mortality rates. Furthermore, the rate of PE in pregnancy is increased five times when compared to non-pregnant women of the same age, and PE is one of the leading causes of death during pregnancy. Therefore, early diagnosis and prompt treatment of PE is imperative. CTPA is usually the gold standard for diagnosing PE. However, because of concerns regarding the radiation dose received, particularly to the fetus, other means of diagnosis may be necessary for pregnant women with clinical signs of PE. In conclusion, the diagnosis of PE among pregnant women is complicated by concerns regarding radiation exposure.

Article Type

Case Report

Publication history

Received date: September 29, 2021

Published date: October 12, 2021

Address for correspondence

Karim Botros, University Hospital Waterford, Ireland

Copyright

©2021 Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science, All rights reserved. No part of this content may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means as per the standard guidelines of fair use. Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

How to cite this article

Karim B. Massive Pulmonary Embolism in Pregnancy and Perimortum Caesrean Section. 2021- 3(5) OAJBS.ID.000332.