Illustrating The Victim Offender Overlap Utilizing the General Strain Theory with Females That Committed Murder: A Criminological Case Study Analysis

ABSTRACT

Ongoing severe, and unjust strains, like adverse childhood experiences, exposure to violence, poor choices, limited employment opportunities, inadequate coping mechanisms, and a lack of a positive support structure, play a pivotal role in explaining females’ acts of murder. Agnew’s (1992) general strain theory (GST) corroborates that ‘today’s victims may easily become tomorrow’s offenders’, supporting the victim-offender overlap with female victims that become offenders of murder. The aim of the research was to illustrate the general strain theory and the victim-offender overlap with the participants that committed murder. The research explored the sources of strain and the victim-offender overlap experienced by three females that committed murder. This juxtaposition of females incarcerated for murder addresses the gap in the literature on the stresses, influences, and circumstances from a theoretical perspective. The research was directed by one research question: Can the general strain theory and the victimoffender overlap explain females’ involvement in murder? Data was collected through interviews and secondary document analysis. A thematic analysis was applied to analyze and interpret the data. The results show that the participants’ acts of murder are directly linked to forms of strain, negative emotional states, inadequate coping mechanisms, poor decision-making skills, low control, and a lack of support.

KEYWORDS

Female offenders; murder; Victim offender overlap; General strain theory; Adverse childhood experiences; Gender based violence

INTRODUCTION

Globally, a third of the female prison population serve sentences for violent offenses, including murder [1]. The storyline of violent female offenders is different from their male counterparts, especially concerning their own victimology [1-3]. Violent females are typified by many sources of strains and emotional states, such as emotional dysregulation, dysfunctional families, normalized violence, personality disorder diagnoses, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), financial problems, limited choices, social isolation, and a lack of support [2,5-7].

Many violent and non-violent female offenders experience negative stimuli and affective states related to a gloomy history of trauma, abuse, physical (i.e., hormone and gynaecological problems), and mental health problems (anxiety, depression, psychological distress, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts), troubled family life (i.e., broken homes and family discord), financial strain, parenting responsibilities, unemployment or underemployment, uneducated and/or under-educated [2,4,5,7-9]. This pattern of historical and repetitive trauma can often be traced from childhood, and adulthood, to leading factors associated with the female offenders’ involvement in violent crime – explaining and supporting the victim-offender overlap in females that committed murder [1,9].

Furthermore, other adverse childhood experiences associated with incarcerated females include absent and aloof parents, poor parent-child attachments, and at-risk children (i.e., displaying violent, aggressive behavior) [5,6,8]. The victim-offender overlap has been well documented [3,6,10]. Pursuant to this, Webster [12] postulates that many women who murder men were themselves victims of abuse by the men they murdered. Victims of violence often respond and retaliate with violence [3,4]. Antisocial activities such as substance abuse and fighting increase the victim’s proneness for victimization, while characteristics such as low self-control, poor coping mechanisms, low frustration tolerance, and lack of empathy, are traits shared by victims and offenders [3,11]. This qualitative research explores the strains, stresses, and negative emotional states linked to the general strain theory (GST), and the victimoffender overlap that contributed to the adult female offenders’ acts of murder.

The General Strain Theory

The general strain theory stems from the social structure theory that connects power, poverty, unemployment, education attainment, and lower social classes to crime [7,8]. Different from other forms of strain theory, Robert Agnew’s (1992) general strain theory (GST) points out that a negative experience, such as exposure to violence, can produce stress. That stress generates strain, which requires coping skills in order not to escalate into criminality [8,13]. The GST maintains that strain (emotional turmoil or inner conflict) and the severity (magnitude) of strain increase the risk of criminal involvement [13,14].

Sources of strain include

1. the failure to achieve one’s goals (i.e., financial success or a stable romantic relationship),

2. a disconnect between expectations (positive familial bonds and emotional happiness) and achievements (i.e., limited education and unstable intimate relationships),

3. removal of positive stimuli (parental rejection and support), and

4. The presentation of negative stimuli (i.e., exposure to violence) [8,14]. These sources of strain create negative affective states, such as anger, anxiety, depression, disappointment, despair, distrust, frustration, and fear [3-6,9,13]. The crux is that without an adequate support structure (i.e., meaningful non-criminal significant others or family members), positive coping mechanisms (i.e., low levels of social control, the ability to positively divert anger, depression, and frustration), sound decision-making skills (i.e., non-violent, non-criminal and pro-social decision-making skills) and non-criminal problem-solving skills, negative emotional states might ease the pathway to antisocial (substance abuse) and criminal (violence, such as murder) behavior [9,14]. In sum, the GST relates to a person losing someone significant or something good, receiving something bad or negative, or the person cannot get what he or she wants [15].

Victim Offender Overlap

According to the victim-offender overlap notion, offenders were victims during, or prior to, their offenses, while victims display a high propensity in becoming offenders [3,10]. The victim-offender overlap is where the victim and the offender merge [11]. Research [3] indicates that victimization by unknown or unfamiliar offenders (such as strangers), decreases victims’ involvement in consequent violent behavior, whereas victimization by a family member or a personal acquaintance increases association with future violent behavior. In a nutshell, research [1,11,16] proves that the closer a victim is to a perpetrator, the more trauma is experienced by the victim, with a heightened risk for the victim to become an offender [3].

Regarding incarcerated females, scholarly research [5,10] found that incarcerated females were subjected to violent, sexual, emotional and property victimization prior to their involvement in crime, highlighting the reciprocal and strong correlation between personal victimization and subsequent involvement in the crime. The victim-offender overlap furthermore shows an association between posttraumatic stress, mental health issues (and diagnosable mental disorders), and substance abuse [6,10]. Adverse childhood experiences are also linked to the victimoffender overlap and include emotional neglect, physical and sexual abuse, an unstable family life, exposure to domestic violence, and familial substance abuse and criminality [3,7,10].

Additionally, a lack of strong relational bonds to parents and to non-criminal peers, poor school commitment, poor choices, inadequate parental involvement and supervision, and low selfcontrol are likely to enact violence and victimization [3,4,6].

METHODOLOGY

A qualitative, case study analysis was utilized to illustrate the strains and stresses, that is, personal experiences related to a phenomenological analysis, of three adult female offenders’ childhood, familial, and social circumstances that contributed to the murder of their spouses and an intimate partner. The aim of the research was to demonstrate the general strain theory and the victim-offender overlap with the participants that committed murder. This research addresses the gap in research on the strains, stresses, influences, and circumstances of females, illustrating their victim-offender overlap from a theoretical perspective regarding their acts of murder. The research was steered by one research question: Can the general strain theory and the victim-offender overlap explain the participants’ involvement in murder?

The sample included three adult female offenders, two participants (case studies A and B) were purposively selected for their crime, namely murder. These participants formed part of the interviewed participants. In-depth personal semi-structured interviews were conducted with these participants and a semistructured interview schedule with pre-identified themes directed the researcher during the interviews. Four interviews were conducted with the female offenders who were housed at a Female Correctional Centre in Gauteng province (South Africa). Each interview lasted approximately 90 minutes. The participants voluntarily participated in the research, consented to their participation, and were briefed beforehand about the aim and focus of the research. The researcher treated the participants with dignity and respect and confidentially was guaranteed to the females. The third participant (case study C) was identified from an out-of-date secondary data document (criminological pre-sentence evaluation report) that is in the public domain of which the researcher is the guardian. The third participant was also purposively selected based on her crime, namely murder. None of the female offenders’ identities, or information revealed in this research, can be traced to the females, ensuring the anonymity of the participants.

Lastly, the researcher used a thematic analysis to unravel the data based on main themes (sources of strain, negative emotional states, victim-offender overlap, and antisocial and criminal behavior). The researcher obtained ethical approval for both the participants (case studies A and B) that were interviewed and for the secondary document analysis of case study C.

DISCUSSION

A summary of the life stories of the three female offenders’ childhood, familial, personal, and social circumstances and experiences are sketched below and linked to their acts of murder. Case studies A and B include personal interviews, and case study C involves a document analysis. Pseudonyms such as ‘Louise’ (Case study A), ‘Martha’ (case study B), and ‘Anna’ (case study C) were assigned to the participants to assure the anonymity of the research participants.

Case Study A (Interview Data)

Louise is a 43-years old Caucasian widow with three children. She passed Grade 9 and was a housewife prior to her imprisonment - she has never been employed. Louise attended a special-needs school due to severe learning problems (as indicated on her institutional file). The participant has a sister of whom she (the participant) is the eldest. Their mother was also a stay-at-home mom and their father “held a management position at a steel company”. The offender divulges that she and her sister endured severe physical and sexual abuse and emotional neglect. Louise orates that her father “made me have oral sex on him while I was kneeling in front of him in his TV (television) chair”. She claims that their father had made her sister watch when he had sexual intercourse with their mother so that “she can see how babies are made”.

The participant relates that their father would “beat us for anything, I would wet myself, then I had to dry myself and then my father would make me take off my clothes, he held me down with his own arm and he would beat me with a belt … sometimes I was bleeding from the beatings”. She alludes that her mother was aware of the sexual and the physical abuse but “she never did anything to stop him … the doors were always open, she must have seen what he was doing to us. She was very scared of him, he gave her hidings too, that was when he drank too much. We (Louise and her sister) would run to our rooms and hide under our blankets”. At the age of 9 years, Louise and her sister were removed from their parents’ care and placed in foster care for four months after which they were moved to a Child and Youth Centre. During this period, Louise cut her wrists on several occasions, and she received psychiatric treatment and medication for anxiety and depression.

The participant recites that “I used to dream of getting out the house, I thought of running away, but I was scared that my dad would find me. I wanted to get married, be happy and be a good mother”. During this period “my father was arrested, and he lost his job. My sister told one of her friends at school about what my father was doing to us, this is how it came out”. At the age of 13-years, Louise and her sister returned to her parents’ care who by then “lived in a small garden flat at the back of a house”. According to Louise, “he never made me have oral sex with him again, and the same with my sister (that is, not making her watch when he had intercourse with their mother), he still beat us, with our clothes on”.

Louise met a man who was 7 years her senior, “he was a mechanic and the son of one of my father’s new friends, he was my first and only love”. At the end of Grade 9 (at the age of 15-years), Louise dropped out of school and married. She states that “I was pregnant at 17-years with our first child (daughter), I was 20-years old when our son was born and 24-years old when our latest son was born. I had a hysterectomy, otherwise, I would have had more children”. The participant notes that they did not have regular contact with her parents and her sister, as her husband “despised them, he said I do not need them anymore. I have my own family, and that they (her parents and sister) are dead to me”.

According to Louise, “he (her husband) drank a lot and then he would beat me ... he once pulled me by my hair while I was lying on the floor - in front of the kids - they were screaming and crying”. The participant unveils that “I had to watch porn (pornography) with him, it made me sick, the oral sex made me think about what my father did to me, and he (her husband) insisted on it (oral sex), I hated it. I told him what my father did to us, and he used this against me and called me a ‘whore’ when he was drunk. There were many times that I thought about ending my life, drinking all the pills in the house, but then I thought of my children and what would happen to them”.

Regarding the murder, Louise posits “that night he started with calling me names … ‘a cheap ugly fat whore’, yelling that I’m good for nothing that not even my father would want me (sexually), something in me snapped, I grabbed the meat knife on the kitchen table, ran after him and stabbed from behind. He dropped to the floor. I stood there, frozen, he was shaking (convulsions) and there was a lot of blood. The kids were in their room, they did not see it. I ran to the neighbors’ house, and they came over to our house. They took the children to their house. I sat with him (her husband), crying, pleading with him, trying to wake him up”. Louise stabbed her husband 17 times. She recalls “my father attended the first week of my trial, he said this (the murder) was your choice, look what you got yourself into, this is not how we raised you, you must live with this for the rest of your life”. After receiving a 12-year sentence, the participant’s father came to visit her once in prison. Since then, she has not seen or heard (telephonic conversations) from her father again. Her mother attended her trial and “she visits me about 4 times a year, I suppose if my dad allows her to come”. Her mother has sporicidal contact with the participant’s children; however, the children do not want to have contact with their mother. Louise’s sister also attended the trial, and she visited Louise once in prison, because “she has her own worries, my mother says her husband does not have a job and they are struggling, so I think she wants to visit me, but she can’t”. Regarding not having contact with her children, Louise surmises “I just wanted to be a good mother and a good wife, with a happy family, now I killed my children’s father, and they will never forgive me, I did not mean to do it, but it is done”. The participant mentions that she contacts (telephonically) the neighbors, “they are the only ones who did not judge me, they pay money into my (correctional) account to buy some extras from the prison tuck shop”.

Case Study B (Interview Data)

sMartha is a 41-years old African widow with two children. Martha completed Grade 12 and she obtained four diplomas within the Banking Industry. Martha was employed at a prestigious bank in a managerial position that specialized in investments, and she states that “I have really worked hard to prove myself, that I’m worth something, I studied at night with small children while my husband was out partying or lying on the couch watching TV … even over weekends. I got a top position at the bank, and I dressed the part. My parents and family were very proud of me, even I thought I did well”. Martha relates that her family was very poor and that both her parents are uneducated. Her mother is a house cleaner, and her father is a gardener. She recaps that “we were really struggling, there were never enough clothes and we (my 2 sisters and I) had to share the clothes between us, even if it did not fit you, we had one meal a day (at night) and then there was bread in the morning with tea - only the food on your plate was what there was, there were no seconds. My parents did not have money for school clothes, so we were teased a lot at school and we received ‘hand-downs’ from other families and from the church, which was very embarrassing to me. But we never complained because we knew our parents did the best they could and they were good parents, they did not waste money on alcohol or other nonsense like partying”. The participant said she always envied girls in the community “with nice and fancy clothes, expensive shoes and shiny hairstyles”. She records “I was very shy because it felt as if all the girls and boys were looking down at me, thinking we are poor and common … I did not have many friends, only two girls who were neighbors on both sides of our house and who were in the same (lower socio-economic) class than us”.

When asked about her marriage and what led to the murder of her husband, Martha replied, “I was often told by people in our community and at church that I am beautiful, I did not feel beautiful, because I linked it with money, nice clothes, shoes, and hair. I did not realize you can be beautiful without money. There was this good-looking guy from the community, obviously not from our area, they were very rich, his father had his own company, and his mother held a high-up position at another company. They had a beautiful 5-bedroom house. He used to check me out, even though he was a bit older (4 years) older than me. We started dating when I was in matric (Grade 12), we chatted a lot, went for walks and he took me to his parental home. I will never forget, I borrowed clothes from the neighbors, trying my best to look classy, I was so nervous. They (her boyfriend’s parents) were very nice to me, and they received me with open hands”. This relationship soon escalated into marriage. Martha’s husband was a director of a group of companies, and she secured herself a job in the banking industry.

According to the participant, after the children were born, her husband would stay out late at night, and at times, he did not come home. She said when she enquired about his whereabouts, “it would end up in a huge fight, us screaming at each other, him telling me I’m ‘a nothing’, that I come from nowhere and that he made me what I am … my job, our house, my car, our lifestyle … my clothes - he made me feel like that poor ‘not-good-enough’ girl from the community, then he would slam the door, get into his car and leave. I never knew where he went, or where he slept over. I would stay up all night crying, thinking about killing myself, drinking (alcohol) to calm myself, trying to think what to do to not provoke him, to be a better wife ... to make him proud of me and to love me”.

However, Martha’s husband’s behavior escalated to him staying out for weekends and when she tried to question him about it, he verbally abused her, referring to her “common and poor background”. Martha decided to hire a private investigator to investigate her husband’s “other life” and it came to light that her husband was having an affair with “a younger and very beautiful girl, she was also high-up, with several degrees, working at a company”. Martha was devastated and “it felt as if my world was tumbling, I had no control over this and I could see he loves her and that he wants her. I tried everything to get him back at the house, to work on our marriage, I lost weight, I went jogging every morning, I never provoked him, but he was not interested”. Then, Martha’s husband told her that is leaving her and that he is moving in with his girlfriend. This had a severe effect on her mental health, as “it started to eat me up inside, I could not eat, sleep, concentrate, work … I drank more and became obsessed with this woman. I would call her; leave her nasty and threatening messages and I would often drive past her house”. Pertaining to the murder, Martha approached two men from her childhood community and paid them R 60 000 (approximately $369.00) to have her husband murdered – “to make it look like a hijacking” as her husband drove a very expensive vehicle that was in demand on the black market in neighboring countries. The staged hijacking happened five weeks later when the hit men accosted Martha’s husband while he was driving from work. They tied him up and put him in the boot of the vehicle. The men drove to a remote area, shot Martha’s husband execution style, placed his body in the bushes, and covered the body with branches. Martha was arrested after one of the contract killers “bragged about the killing at a community bar while buying everyone drinks”. She received a 25-year (life) imprisonment sentence.

Although Martha did not have much contact with her parents and sisters during her marriage, “I was ashamed that I could not keep my husband, I did not want them to know about it and that he left me. I sent them money every month and I spoke to them on the phone … and with my sisters. I did not go home as I knew they would know that something was wrong”. Martha’s parents attended her trial. Her children were sent to her late husband’s family who moved to another province, and since her arrest, Martha has had no contact with her children or with her late husband’s family, “they do not take my calls, my parents spoke to them, and they told my parents never to contact them again and that they do not want anything to do with me”.

Case Study C (Secondary Data Analysis)

Anna is a 31-year-old African lady who completed Grade 9. She has three children from two different fathers. According to her, she was customarily married (married in terms of custom and not according to the law, which is also known as a civil marriage) to the father of her first and second-born children and she was cohabituating with the late father of her last (third) child. Anna was never employed, and she relied on the fathers of her children for financial support. The participant orates that “we grew up very poor, my father was a jack of all trades, he did not always have work, and my mother was unemployed. There was not always enough food for us, the neighbors and some of my father’s friends would help us out with food. There was always money for booze (alcohol) and dagga (marijuana) for my parents”. When my father drank too much he would fight with my mother and he would beat her up badly, she went to the local clinic a few times for medical assistance. Everyone (staying) around us knew about this, but it was common in our area, with many households around us there was violence and the people used alcohol and dagga”.

The participant recalls that her father would also beat her and her two siblings if they did not do their house chores correctly, “at times my face was swollen and my body ached, we tried to hide the bruises”. Anna says she “wanted to go to university and study, have a better life than her parents, and get away from the poverty and drugs”. However, she became pregnant at the age of 15-years, dropped out of school, and stayed with her parents. “My father was very upset about my pregnancy, he said I was sleeping around with boys at school, and that I was a cheap girl. I got pregnant after I dated the father of my first two children. He completed his matric as if nothing happened and we had another child when I was 18-years old. His parents supported the children financially and both the children went to live with his (the husband) parents as they did not think my home is a good environment for the children to be in … with the alcohol and dagga and my father beating my mother and my siblings”.

Martha’s husband “moved on with his life, even though we were married, he dated other girls and I did not have contact with him anymore. I went to visit my children over weekends, seeing them during the day, but I never brought them home. During this period, Martha met the father of her last child. “I would go out at night drinking with girlfriends at the local bar and I also started to smoke dagga. It (the alcohol and dagga) made me feel better about my children not living with me, I felt like a bad mother, a failure … but I knew they (the children) were better off with my husband’s parents”. Anna’s boyfriend was 6 years her senior and he was working in the construction business. “He earned a good salary; he was a manager. In the beginning, he splashed a lot of money on me, he took me shopping for clothes at big malls and he took me to restaurants – this was the first time in my life that I went to a restaurant, I did not even understand the food on the menu”. After a year, Martha became pregnant and her partner ‘was very happy about the baby”.

The participant proclaims that “we were happy the first three years - after our son was born – then, he (her partner) turned on me, hitting me and cheating on me with other girls. I felt threatened as I had a good life, staying in a nice house, we had enough food and clothes ... we went on holidays, and this just stopped”. Anna reports that her alcohol and dagga usage increased, and it escalated to her using Tik (a tablet that consists of amphetamines, talcum powder, baking powder, starch, glucose, and Quinine). Because of her substance abuse, her child was sent to live with her parents and her partner paid her parents money for the child’s monthly expenses.

Concerning the murder, “he came home after drinking at a bar with other girls, he found me drunk and high on the dagga and Tik, he started beating me and swearing at me. I ran to the room, grabbed his gun and I shot him. I did not realize what I was doing”. Anna shot her partner three times and he died at the scene. She received a 15-year imprisonment sentence. Her parents attended her trial, and they visit her at the prison “if they have money to travel to prison”. She does not have contact with her other children or with her husband (to whom she is still married).

RESULTS

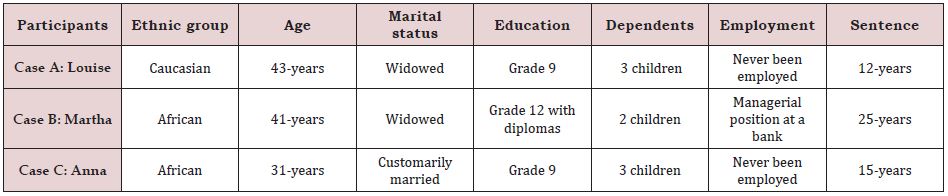

The findings link various sources of strain; negative emotional states; poor coping mechanisms, decision-making, control, and support; and the victim-offender overlap to the participants’ acts of murder. Table 1 provides the demographic details of female participants that committed murder (Table 1) outlined the female participants’ demographic details. The sample consisted of two African females and one adult Caucasian female. The youngest participant (case study C, Anna) was 31-years old, followed by case study B, Martha, who was 41-years old, and case study A, Louise, the eldest, who was 43-years old. Two of the participants were widowed (case study A, Louise, and case study B, Martha), while only participant (case study C, Anna) was customarily married. Case study B (Martha) obtained the highest education with Grade 12 and diplomas within the Banking Industry, while both cases A (Louise) and C (Anna) obtained Grade 9. All the participants had children - cases A (Louise) and C (Anna) had each three children, whereas case study B (Martha) had two children. Case study B (Martha) serves a life sentence (25-years), followed by case study C (Anna) who serves the second-longest sentence of 15-years, followed by case study A (Louise) who is serving a 12-year imprisonment sentence. All the participants are first-time offenders.

Regarding case studies A (Louise) and C’s (Anna) low educational accomplishment, research [6,7] indicates that adverse childhood experiences are linked to poor educational achievement. In this regard, limited education is associated with socio-emotional well-being factors [3,4,7], such as low self-worth (in both case studies A, with Louise and C, Anna) [3,7], suicidal ideation (cases A, Louise, and B, Martha) [4,7], self-harm behavior (case study A, Louise) [4,7,17] and psychiatric involvement (case study A, Louise) [7,17]. Both cases A, Louise, and C, Anna, displayed psychological distress and mental health issues (i.e., anger management, anxiety, depression, fear, sadness, and social withdrawal) that according to research [3,5,6,7,11] is linked to limited education. Furthermore, research [3,6,7] proves a direct link between low school involvement and dropping out of school as is the case with cases A, Louise, and C, Anna.

Concerning the female participants and their children, research [5,16,18] illustrates that females’ own victimization experiences (i.e., trauma, adverse childhood experiences and adulthood exposure to abuse and violence) have a steadfast link with poor parent-child attachments. Incidentally, case studies (cases, A - Louise, and C - Anna) had little control over the domestic violence that their children were subjected to [1,2,5,9]. All three cases could not safeguard or protect their children against emotional abuse, neglect, and domestic violence. During this time (of their own victimization), the mothers exhibited strained parent-child bonds and poor emotional involvement and supervision [1,6,9]. Research [16] explains that women that were victims of childhood abuse (physical, sexual, emotional, and neglect), might transfer the cycle of abuse and violence to their children, and that ongoing abuse (i.e., domestic violence and verbal abuse) [12,20] directly affects children with regards to aggressive and antisocial behavior with an increased risk of aggressive acts by the woman [16].

Sources of Strain and Negative Affective States

Research [8,9,13,15,20] demonstrates the link between sources of strain, negative emotional states, antisocial behavior and involvement in murder. Although limited education, strained mother and child bonds, and failure to safeguard and protect children against gender-based violence were explained in Table 1, these sources of strain need to be indicated and reiterated with the GST’s sources of strain.

According to the GST [8,13], the sources of strain for the three female participants included 1) Failure to achieve goals during childhood for the female participants comprised poor school achievement (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [6,7,9], a void in a positive support structure (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [9,15], a void in parental bonds (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [6,9,19], non-violent living circumstances at home (cases A, Louise and C, Anna) [4,15], harsh/unfair/excessive punishment (case A. Louise) [9,15], parental substance abuse (case C, Anna) [6,9,15,17 ], uninvolved parents, and poor supervision (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [4,6,7,9,15], physical abuse (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [4,5,9,15,18], sexual abuse (case A, Louise) [5,9,15], neglect (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [5,9,15], emotional abuse (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [5,9,15], domestic violence (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [2,7,9,15,18,20], financial better living circumstances and escaping poverty (cases B, Martha, and C, Anna) [1,7,9,15], and acceptance by friends from higher classes (case B, Martha) [9].

Many of the unachieved childhood goals escalated into adulthood and included a lack of an extended support structure (cases A, Louise, B, Martha, and C, Anna) [2,9,12,15,20], school attainment (cases A, Louise and C, Anna) [7,9], employment (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [7,9,18], an unloving, uncaring, and an unstable intimate relationship (cases A, Louise, B, Martha, and C, Anna) [5,7,9,15], inattentive, emotionally unavailable and unstable mothers (during the time of own victimization) (cases A, Louise, B, Martha, and C, Anna) [1,5,16], emotional abuse (cases A, Louise, B, Martha, and C, Anna) [7,9,12,15,21], physical abuse (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [5,7,9,15,21], power imbalance – male dominance (cases A, Louise, B, Martha and C, Anna) [2,15], financial issues (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [1,9], failure to protect children from emotional abuse (cases A, Louise, B, Martha, and C Anna) [1,2,9], failure to protect children from domestic violence (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [2,9,15], failure to break the cycle of violence and abuse (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [9,16,21], and abandonment by her father (case A, Louise) [9].

The next source of strain is 2) Disconnection between expectations and achievements The GST holds that expectations that are not realized turn into stresses and strains [9,13]. The expectations of the female participants included adequate schooling (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [7,9], positive bonds with parents (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [5,6,9,16], protection from abuse, and exposure to domestic violence (cases A, Louise and C, Anna) [1,16,17], stable intimate relationships (cases A, Louise, B, Martha, and C, Anna) [5,12,16], respect from parents and intimate partner/husband (cases A, Louise, B, Martha and C, Anna) [5,7,17], to be an emotionally available, attentive and a ‘good mother’ to the children (during times of own victimization) (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [5,7,9,16], better socio-economic class during childhood and to eliminate poverty and low income (cases B, Martha, and C, Anna) [1,5,9,17], positive bonds with parents (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [5,9,17], and employment (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [7,9,17].

The achievements that were never realized included school achievement (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna), employment (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [7,9,15], positive bonds with parents (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [6,9,17], to be protected from childhood abuse (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [9,16,17], non-abusive and stable intimate relationship (cases A, Louise, B, Martha, and C, Anna) [5], love and respect from intimate partner/husband (cases A, Louise, B, Martha and C, Anna) [5,6,9,17], love and respect from parents (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [5,9], to be a ‘good’ mother (during times of own victimization) [5,9,16] and a ‘good’ wife (cases A, Louise, B, Martha, and C, Anna) [2,9,15].

Following this, is the third form of strain, 3) Removal of positive stimuli for the female participants during childhood, which encompassed school attendance (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [7,9], parental attention, love, involvement, and protection from abuse and positive attachments with parents (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [2,15,17], and acceptance by girlfriends regarding socio-economic circumstances (case B, Martha) [9,17]. During adulthood, the removal of positive stimuli involved the father’s approval (case A. Louise) [16]. All the participants experienced the removal of their husbands’/intimate partner’s love and respect [2,3], relationship and power equality [2,12,20], positive bonds with children (at times of own victimization) [5,16], and parental and familial support [5,15].

The last form of strain involves, 4) Presentation of negative stimuli that presented itself during the participants’ childhood in the form of poor parent-child bonds (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [6,7,9], childhood abuse (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [7,15], lack of support (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [15,18], lack of protection against abuse and domestic violence (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [2,9,15], lack of parental love, attention, and supervision (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [1,5,9], out-of-home placement (case A, Louise) [9], poverty (cases B, Martha, and C, Anna) [9,15], bullying and victimization (case B, Martha) [9], and dropping out of school (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [6,7].

During adulthood the presentation of negative stimuli for the female participants included poor choices with regards to crime (cases A, Louise, B, Martha and C, Anna) [5,6], not protecting their children from emotional abuse and domestic violence (cases A, Louise, B, Martha, and C, Anna) [5], substance abuse (cases B, Martha, and C, Anna) [6,9,12], financial strains (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [5,9], unemployment (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [4,7,9], lack of support during intimate relationship/marriages (cases A, Louise, B, Martha, and C, Anna) [12,15], gender-based violence (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [2,4,9,15], emotional abuse (cases A, Louise, B, Martha, and C, Anna) [2,4,9,15] and neglect (cases A, Louise, B, Martha, and C, Anna) [2,5,9,15]. Research [8,9,13,15] stipulates that the four types of strains created negative emotional states. The female participants experienced feelings of helplessness and hopelessness, humiliation and shame, and low self-esteem (cases A, Louise, B, Martha, and C, Anna) that were linked to childhood abuse and neglect (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna), poverty (cases B, Martha, and C, Anna), not completing school (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna), a suicidal attempt and ideation (Case A, Louise), learning problems (case A, Louise), social isolation (cases A, Louise, B, Martha, and C, Anna), not being accepted by friends (case B. Martha), and distrust in people as a result of the abuse (Cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) [1,3,9,15,22-24].

Due to the emotional and physical abuse, neglect (cases A, Louise, B, Martha, and C, Anna), and betrayal (case B, Martha) experienced during their marriages and intimate relationship, the female participants’ negative emotional states were induced by low self-worth, psychological distress and mental health issues (i.e., anger, anxiety, dissociation, distrust, depression, fear, sadness, and social withdrawal), despair (i.e., feelings of helplessness, hopelessness, and desperation), and suicidal ideation (cases A, Louise, and B, Martha) [1,3,5,9,15,18,19,22].

Coping mechanisms, decision-making skills, low control and support

The female participants’ acts of murder are linked to their miserable family circumstances, abusive intimate relationships, and inadequate coping mechanisms that were enhanced by their negative emotional states (i.e., anger, anxiety, psychological distress, and mental health issues) [1,5,17,24,25,26,27]. This was escalated by social isolation, inadequate support structures, low levels of social- and self-control, and the inability to manage their negative emotional states in a positive and non-criminal manner [1,15,17,23, 28,29]. Lastly, poor choices and poor decision-making skills (i.e., non-violent, non-criminal, and pro-social decisionmaking skills) pushed the participants to murder their spouses and intimate partner [27-32].

All three of the female participants (cases A, Louise, B, Martha, and C, Anna) lacked the skills and the ability to negotiate with their husbands and intimate partners to terminate the abuse. Two of the participants (cases A, Louise, and C, Anna) lacked the resources to legally cope on their own. Although money is a great coping resource (i.e., to acquire goods and services such as counsellors and lawyers), it did not count in Case B’s (Martha) favor as she could not win her husband’s love, affection, and loyalty back [15,17]. Criminal coping, or the murder of the female participants’ spouses and intimate partner, became a reality because of inadequate coping mechanisms, poor decision-making skills, low control, lack of support, and the females’ negative emotionality [13,15,17,20].

Victim Offender Overlap

Research [10,11] illuminates that the mainstream of incarcerated women were victims of various forms of abuse, neglect, violence, and crime, in fact, well before being charged with a crime. However, the women normalized (perceiving it as natural or normal) the abuse and violence against them [10]. The GST magnificently explains the victim-offender overlap with strains that create negative affective states that, if not positively addressed or resolved, might turn into antisocial and criminal behavior [15,17,25]. Based on the aforesaid, the GST illustrates how a victim can become a perpetrator and that there is a consistent relation between personal victimization and offending behavior [10,12,20]. Thus, there is a reciprocal relationship between victimization and involvement in crime [10,11,16].

Often, female victims of abuse and violence react and retaliate with violence as a form of release of the strains and negative emotional states experienced, as was the case with the female participants (cases A, Louise, B, Martha, and C, Anna) [15,23,33]. With the sample of participants that committed murder, the abuse and violence that they experienced were mimicked and utilized as a form of retaliation, ‘self-help’ and/or because of a result of a spillover of an amalgamation of factors (i.e., strains, stresses, negative emotional states, poor coping mechanisms, inadequate decisionmaking skills, low support, and low control) (3,4,11]. In this regard, the GST, cycle of violence, and the victim-offender overlap effectively explain how the three female participants became involved in the murder of their spouses and intimate partner [3,11,12,20].

Implications and Limitations of Research

The richness of this qualitative research efficiently explained how the three female participants’ sources of strain and negative emotional states, coincided with their victim-offender overlap. This research provided the participants with a voice pertaining to their personal victimization and the build-up and link to the murder of their spouses and intimate partner. The findings highlight that participants incarcerated for violent offenses remain a vulnerable and under-research population [12,20]. However, due to the sample size, the findings of this research cannot be generalized to all females incarcerated for violent crimes. It should rather be interpreted as a sample-specific contribution to research on females who murdered their spouses and intimate partners.

CONCLUSION

Females incarcerated for murder are a marginalized group of offenders. This research illustrated how Agnew’s GST’s sources of strain (failure to achieve goals, disconnection between expectations and achievement, removal of positive stimuli, and negative affective states), supported by the victim-offender overlap, contributed to their involvement in the murder of their spouses and intimate partner. The aim of the research, namely, to demonstrate the general strain theory and the victim-offender overlap with the female offenders that committed murder was attained. The sources of strain that the participants experienced during childhood (i.e., adverse childhood experiences and poverty) and adulthood (i.e., emotional and physical abuse and neglect); and their negative emotional states (i.e., psychological distress and mental health issues) are linked with poor coping mechanisms, inadequate decision-making skills, low control, a lack of support, antisocial behavior (i.e., substance abuse) and criminality. This consolidation of strains, negative affective states, lack of skills and victim-offender overlap successfully explained the participants’ involvement in murder.

REFERENCES

- Gower M, Spiranovic C, Morgan F, Saunders J (2022) The criminogenic profile of violent female offenders incarcerated at Western Australian prisons as per the level of service / Risk need, responsivity (LS/RNR) and violence risk scale (VRS). Psychiatry, Psychology and Law 1-19.

- Kunsunoki, Y, Bevilaqua K, Barber SJ (2022) The dynamics of intimate relationships and violent victimization among young women. J Interpers Violence 1-9.

- Zimmerman GM, Farrell C, Posick C (2017) Does the strength of the victim offender overlap depend on the relationship between the victim and perpetrator? Journal of Criminal Justice 48: 21-29.

- Hesselink AME (2022) The nexus between females who kill and HIV/ aids: exploring the contributing factors to this complex phenomenon. Journal of Asian and African Studies (JAAS) 1-22.

- Brennan T, Breitenbach M, Dietrich F (2010) Unraveling women’s pathways to serious crime: new findings and links to prior feminist pathways. American Probation and Parole Association 4(2): 35-37.

- Jennings WG, Higgins GE, Tewksbury R, Gover AR (2010) A longitudinal assessment of the victim-offender overlap. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 25(12): 2147-2174.

- Otero C (2021) Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and timely bachelor’s degree Attainment. Social Sciences 10(2): 44.

- Kandrat AG, Connolly, EJ (2022) A examination of the reciprocal relations between treatment by others, Anger and antisocial behavior: A partial test of general strain theory. Crime and Delinquency: 1-19.

- Siegel LJ, Worrall JL (2016) Introduction to Criminal Justice. In: (16th edn), Cengage Learning, USA.

- Bucerius SM, Jones DJ, Kohl A, Haggerty KD (2020) Addressing the victim-offender overlap: advancing evidence-based research to better service criminally involved people with victimization histories. Victims and Offenders: An International Journal of Evidence-based Research, Policy and Practice 16(1): 148-163.

- Berg MT (2012) The overlap of violent offending and violent victimization: assessing the evidence and explanations. In: DeLisi M, Conis PJ (eds.). Violent Offenders: Theory Research Policy and Practice. Burlington, USA, pp 17- 38.

- Webster R (2021) Women who kill: Justice for women who kill. Russell Webster.

- Agnew R (1992) Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology 30(1): 47-88.

- (2022) Agnew general strain theory explained, health research funding.

- (2022) Criminal justice, criminal justice research, strain theories.

- Augsburger A, Basler K, Maercker A (2019) Is there a female cycle of violence after exposure to childhood maltreatment? A meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine 49(11): 1776-1786.

- Isom DA, Grosholz, JM, Whiting S, Beck T (2021) A Gendered look at latinx general strain theory. Feminist Criminology 16(2): 115-145.

- Lundholm L, Haggard U, Möller J, Hallqvist J, Thiblin I (2013) The triggering event of alcohol and illicit drugs on violent crime in a remand prison population: A case crossover study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 129(1): 110-115.

- Nuytiens A (2015) Female pathways to a crime and prison: Challenging the (US) gendered pathways perspective. European Journal of Criminology 13(2): 195-213.

- Webster R (2021) Women who kill: Justice for women who kill. Russell Webster.

- (2016) Gender based violence (GBV) in South Africa: A brief review. The centre for the study of violence and reconciliation (CSVR). South Africa Pp. 1-20.

- Trestman RL, Ford J, Zhang W, Wiesbrock V (2017) Current and lifetime psychiatric illness among inmates not identified as acutely mentally ill at intake in Connecticut’s jails. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 35(4): 490-500.

- Green BL, Miranda J, Daroowalla A, Siddique J (2005) Trauma exposure, mental health functioning and program needs of women in jail. Crime and Delinquency 51(1): 133-151.

- Sun IY, Haishan L, Wu Y, Lin WH (2016) Strain, negative emotions, and level of criminality among chines incarcerated women. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 60(7): 828- 846.

- Anumba N, DeMatteo D, Heilbrun K, (2012) Social Functioning, Victimization, and Mental Health Among Female Offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior 39(9): 1204-1218.

- Wooditch A, Tang LL, Taxman, FS, (2014) Which criminogenic need changes are most important in promoting desistance from crime and substance abuse? Criminal Justice and Behavior 41(3): 276-299.

- Morash M, Kashy DA, Cobbin JE, Smith SW (2017) Characteristics and Context of women Probationers and Parolees Who Engage in Violence. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 45(3): 381-401.

- Zavala E, Sphon RE, Alarid LF (2019) Gender and serious youth victimization: assessing the generality of self-control, differential association, and social bonding theories. Sociological Spectrum 39(1): 53 -69.

- Lynch SM, Fritch A, Heath NM (2012) Looking beneath the surface: the nature of incarcerated women’s experiences of interpersonal violence, treatment needs and mental health. Feminist Criminology. 7(4): 381- 400.

- Dennis JP (2012) Girls will be girls: childhood gender polarization and delinquency. Feminist Criminology, 7(3): 220-233.

- Friedstad C (2012) Making sense, making good, or making meaning? cognitive distortions as targets of change in offender treatment. Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 56(3): 465-482.

- Palmer EJ, Hatcher RM, McGuire RM, Hollin CR (2014) Cognitive skills programs for female offenders in the community. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 42(2): 345-360.

- Solomon BJ, Davis LEG, Luckham B (2012) The relationship between trauma and delinquent decision making among adolescent female offenders: mediating effects. Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma 5(2): 61-172.

Article Type

Research Article

Publication history

Received Date: September 05, 2022

Published: November 03, 2022

Address for correspondence

Anni Hesselink, Professor, DLitt et Phill in Criminology, researcher, and criminologist at the Department of Criminology and Security Science, School of Criminal Justice, College of Law, University of South Africa (UNISA), South Africa

Copyright

©2022 Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science, All rights reserved. No part of this content may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means as per the standard guidelines of fair use. Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

How to cite this article

Anni Hesselink. Illustrating The Victim Offender Overlap Utilizing the General Strain Theory with Females That Committed Murder: A Criminological Case Study Analysis. 2022- 4(6) OAJBS.ID.000510.