Conservative Femoral Revision: A position Paper and Treatment Framework

ABSTRACT

Background: With overall numbers of hip revisions on the increase in the Asia Pacific and patients undergoing surgery there is

a growing need to perform more conservative surgery. Surgeons need to plan for further surgeries in the future. This paper aims to

describe a conservative approach and hopefully reduce this future burden.

Methods: To address these issues a consensus group was formed to discuss the revision trends across various countries within

the Asia Pacific region. The results of this discussion were used to formulate a framework for how surgery could be planned and

what implants would allow more preservation of femoral bone and hopefully allow more straight forward re-revision surgery if

required in the future.

Results: The group felt in femoral revision cases of Paprosky 2a or less many can be managed with minimal bone loss. If possible,

Metaphyseal loading implants can be used with or without osteotomy to preserve distal bone for the future. Where possible cement

in cement techniques can be used to avoid more distal bone loss. Distal fitting or endoprosthesis implants should be reserved for

2b cases with severe bone loss.

Conclusion: There is an increasing demand for revision surgery, and more patients may require multiple revision surgeries.

When planning for revision surgery there is a need to consider and plan for the next revision in the future. The aim of conservative

hip revision should focus on protecting bone stock for future treatment whilst reducing the risk of re-revision.

INTRODUCTION

Revision total hip arthroplasty (THA) procedures continue to increase, with a growing number of younger patients are having THA and outliving their primary implant [1]. The trend in Asia Pacific is similar, the number of revision THA procedures is increasing in countries such as Japan [2]. In Australia approximately 65% of patients undergoing revision THA are under the age of 75 years [3]. Revision total hip replacements are not expected to last forever, approximately 9.6% require re revision surgery at 3 years and 15% at 10 years [3]. These trends imply a potential increase in the demand of re revision THA surgery and the number of patients requiring multiple revisions. The philosophy for revision THA needs to be reviewed to take into consideration surgical planning for future surgeries. Appropriate implant choices and surgical planning is required to help preserve bone stock, protect the surrounding tissues and potentially reduce the risk of early re revision. This paper aims to describe the principles and a common framework for Femoral revision across Asia-Pacific for treating patients who require revision surgery using a conservative approach; with an aim to reduce the surgical burden to the patient, surgeon and hospital whilst reducing the risk of re revision in the future.

Bone Preserving Techniques

Traditional revision pathways tend not to address ways to preserve bone even though in theory bone conservation would be recommended and considered. Revision constructs tend to rely on distal fixation with little consideration for the use of metaphyseal loading femoral stems. Based on the Paprosky score, 89% of revision THA is for type I, II and IIIA defects, and therefore does not usually require a distal fixating stem [4]. In cases where there is sufficient bone stock, the choice of a revision stem that offers a conservative option will help to preserve bone. The benefit of selecting a conservative hip stem option for the mild to moderate defects will help preserve bone for future THA, should the need to re-revise occur. Previous studies have shown a more conservative approach in Revision TKA surgery can reduce the incidence of rerevision surgery for patients in the future. Further work is ongoing to assess if a similar trend occurs in revision THA [5].

Soft tissue laxity can often be an issue in revision THA, preserving surrounding soft tissue is another consideration when choosing an appropriate stem. The choice of femoral stem with both standard and high offset which provides the opportunity to directly lateralise the stem provides the option of increasing soft tissue tensioning without altering leg length. The choice of a femoral stem should be the most conservative stem appropriate to treat the patient, ideally an implant that will load the bone proximally and preserve bone as much as possible. Distal fixation is not always necessary; a revision hip stem with distal fixation is not usually required for type I and II Paprosky defects. The primary consideration when choosing an implant is achieving stability, with medial support more important than lateral support. In the absence of great trochanter, a femoral stem that achieves proximal medial support with vertical, rotational and flexural stability will suffice. The surgical aim should be to choose a stem to make the revision THA look like a primary hip replacement where possible [6].

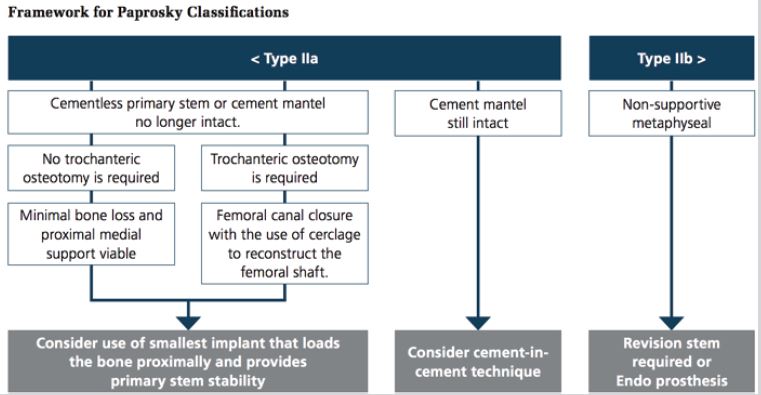

Careful removal of the primary stem to preserve bone and adjoining anatomy is an important consideration for pre-surgery planning. Removal of primary implants safely is as important as the revision surgery and the revision implant choice. In cases where an extended trochanteric osteotomy is required, consider femoral canal closure with the use of cerclage wiring to reconstruct the femoral shaft. This will allow the implants and any bone cement to be removed with minimal bone loss. The femoral preparation can then be carried out as if the femur were closed. The primary stability of the stem inside the host bone is the critical factor. In the case of a highly enlarged metaphysis, consider the shape of the stem required and fill the gaps with bone graft [7]. Defects that were previously filled with impaction bone grafting are now more commonly reconstructed with these uncemented implants. 10 Revision femoral stems do not need to be cemented; consideration of uncemented stems to encourage bone regeneration should be used where appropriate. Regenerate missing bone with the use of bone graft or bone graft substitute and try to minimise the use of augments. When planning for revision total hip surgery, consideration for future THA surgery should be planned by looking at ways to encourage bone generation. Treatment options and surgical planning to avoid a therapeutic escalation with complex surgical treatment is always necessary in revision THA. The use of long stems with distal fixation, or mega-prosthetics should be reserved for the more complex revision procedures where there is a lack of proximal medial support and the canal is capacious. A summary of these principles is shown in Figure 1 below.

Cement-in-Cement Revision

The removal of all the primary stem cement mantle is important if the intention is to revise with an uncemented hip stem. Where the cement mantle remains intact, consider the use of a cementin- cement revision technique. This technique is well established and is useful in cases where revision surgery is required due to a loose femoral component, or to repair periprosthetic fracture in patients who are not fit for prolong surgery and is useful for elderly patients [7]. It has been shown that the introduction of the new wet cement will form a chemical bond with the old cement mantle. The new cement mantle has 94% of the shear strength of the old cement mantle and is stronger than the old cement-bone interface. Even in the cases where there is possible fatigue to the old cement mantel, the integrity of the new bone-cement construct is not adversely affected [8]. Unlike in primary cemented hip procedures, where cement pressurisation in cancellous bone is required to ensure bony interlock, a runnier cement can be used in cement-in-cement revision procedures. The surgeon needs to be aware that the cement must be applied earlier than usual to allow chemical bonding between the new cement and the pre-existing mantle. This also helps to provide the surgeon with extra time to place the revision stem in the correct version and deep enough into the cement mantle to achieve correct leg length and offset. The cement-in-cement revision surgery techniques eliminates the need to remove the primary cement mantle, this helps to reduce blood loss and surgical time and the risk of perforating the femur. Surgical time and blood loss are reduced which reduces the risks of complications for the patient. Less equipment is required and bone stock is retained for any potential future procedures [9].

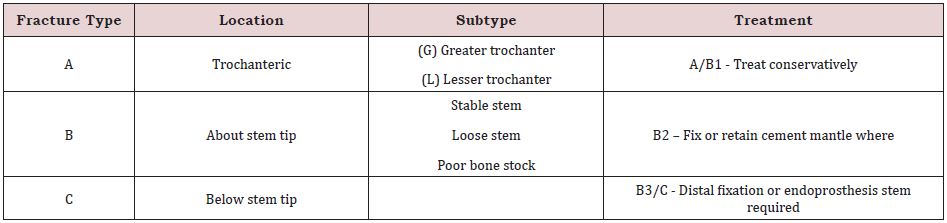

A Barrack grade “A” cement mantel is not required for this revision surgical technique. This approach can be considered in patients that only have a stable bone cement interface below the lesser trochanter. In the case of periprosthetic fractures, a Vancouver B1 or B2 fracture repair can be achieved by the repairing the fractured cement mantle and bypassing the femoral fracture. This is summarised in Table 1 below. Table 1, Management summary in periprosthetic femur fracture dependant on Vancouver grade [10].

Case Example

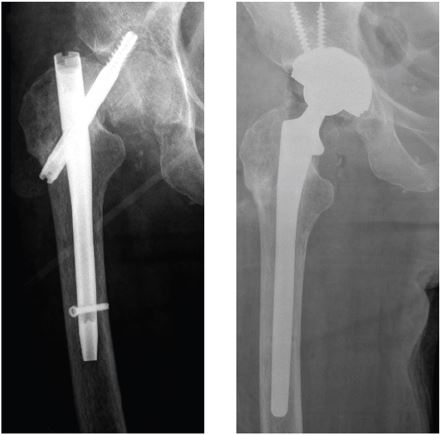

A 90-year-old lady with fixation for Neck of Femur fracture. Gradual migration shows proximal screw penetrating the articular surface of the acetabulum with bony destruction. Treated conservatively with a Revision stem loading proximally and distally. The patient recovered and was independently mobile with a walker frame at home post op. X-rays are shown in Figure 2 below.

CONCLUSION

There is an increasing demand for revision surgery, and more patients may require multiple revision surgeries. When planning for revision surgery there is a need to consider and plan for the next revision in the future. The aim of conservative hip revision should focus on protecting bone stock for future treatment whilst reducing the risk of re-revision. Choosing the most appropriate femoral stem, that provides optimal fixation for that individual patient, with careful pre-operative planning taking into consideration the safe removal of the primary implant while protecting the surround bone and tissue should be the focus. Conservative hip revision conserves bone reduces surgical burden to the patient, surgeon and hospital. Previous work from our department has shown how integrating a diagnostic algorithm with a conservative Revision TKA approach has led to a reduction in Re-revision rates for our patients. Further work in ongoing in combination with the AOANJRR to evaluate if similar results are achieved using this philosophy for Revision THA.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This article summarises the results of the discussion from the Steering Committee at the Asia-Pacific Excellence and Leadership in Training and Education meeting, which was held in October 2017 in Bangkok, Thailand. The Steering Committee was organised by John Patrick Steward of DePuy Australia and led by Tim Board (UK) and Anil Gambhir (UK). It was composed of members from Australia, India, Japan and Thailand. Its goal is to establish a common framework and key principles for revision THR in Asia- Pacific.

REFERENCES

- Schmitz M, Timmer C, Hannink G, Schreurs B (2018) Systematic review: lack of evidence for the success of revision arthroplasty outcome in younger patients. Hip Int.

- (2017) The Japanese society for replacement arthroplasty.

- (2017) Australian orthopaedic association national joint replacement registry (AOANJRR). Revision Hip and Knee Arthroplasty.

- Paprosky W, Greidanaus N, Antonio J (1999) Minimum 10-Year-Result of Extensively Porous-Coated Stems in revision hip arthroplasty. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 369: 230-242.

- Holt G, Hook S, Hubble M (2011) Revision total hip arthroplasty: the femoral side using cemented implants. Int Orthop 35(2): 267-273.

- Rosenstein A, MacDonald W, Iliadis A, McLardy-Smith P (1992) Revision of cemented fixation and cement-bone interface strength. Proc Inst Mech Eng H 206(1): 47-49.

- Briant-Evans TW, Veeramootoo D, Tsiridis E, Hubble MJ (2009) Cementin- cement stem revision for Vancouver type B periprosthetic femoral fractures after total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthopaedica 80(5): 548-552.

- Keeling P, Lennon AB, Kenny PJ, O’Reilly P, Prendergast PJ (2012) The mechanical effect of the existing cement mantle on the in-cement femoral revision. Clin Biomech 27(7): 673-679.

- Wilson CJ, H Saluja, G Wong, Jackman E, Krishnan J (2020) Design, Construction and early results of a formal local revision knee arthroplasty registry. The Journal of Knee Surgery 34(12):1284-1295.

- Wilson CJ, Tait G, Galea G (2003) Utilisation of bone graft by orthopaedic surgeons in Scotland. Cell and Tissue Banking 3: 49-58.

Article Type

Review Article

Publication history

Received Date: March 16, 2022

Published: April 13, 2022

Address for correspondence

Christopher J Wilson, Flinders Medical Centre & Flinders University, South Australia, Australia

Copyright

©2022 Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science, All rights reserved. No part of this content may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means as per the standard guidelines of fair use. Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

How to cite this article

Christopher J Wilson. Conservative Femoral Revision: A position Paper and Treatment Framework. 2022- 4(2) OAJBS.ID.000434..

Figure 1: Vancouver classification of periprosthetic femoral fractures after total hip arthroplasty.

Figure 2: Vancouver classification of periprosthetic femoral fractures after total hip arthroplasty.

Table 1: Vancouver classification of periprosthetic femoral fractures after total hip arthroplasty.