Approach of Intern Doctors to Antibiotic Prescription for Sore Throat

ABSTRACT

Objective: While former studies have investigated the approach of general practitioners (GPs) to antibiotic prescription, there

is scarce evidence on the prescription trends for young, primary care doctors despite their cardinal role in the overall practice

of antibiotic administration. The research aimed to study the approach of young doctors towards antibiotic prescription for a

commonly encountered ailment, sore throat.

Methods and Materials: A cross-sectional study of the interns’ clinical approach was conducted at CMH Lahore Hospital. A

questionnaire containing four clinical vignettes, each with various presentations of sore throat was given to interns chosen by

random, convenience sampling and 80 interns with a minimum clinical experience of 6 months participated in the study.

Results: Vignette 1, a child with tonsillitis had a good overall pick by 86% interns, and 93% of them correctly pursued to prescribe

antibiotics. Vignettes 2 and 4, an adult and child with probable viral, upper respiratory tract infections (URTI) had a lower but

noticeable prescription rate of 11% and 10%, respectively. Vignette 3, a supposed case of glandular fever was correctly inferred by

nearly half (57%) of the interns, however the antibiotic prescription rate high at 59%. There was no difference in prescribing rates

between male and female interns.

Conclusion: Young primary care doctors frequently prescribed antibiotics despite the underlying etiology. It can be inferred that

young doctors lacked knowledge of the pathophysiology of various presentations of sore throat, e.g., bacterial, viral, as well as the

latest guidelines on antibiotic administration.

KEYWORDS

Antibiotic resistance; Antibiotic misuse; Infectious mononucleosis; Intern; Sore throat; Throat swab; Upper respiratory tract infections

INTRODUCTION

Sore throat is the primary symptom of pharyngitis [1]. About 10% of people present to primary healthcare services with sore throat each year [2,3]. Etiologically, it is caused by a variety of microbiological agents. Only 20 percent in children and 5 percent in adults is caused by bacterial agents such as group A betahemolytic streptococci (GABHS) [4]. Otherwise, most pharyngitis cases (40-80%) are self-limiting and viral in origin, mainly owing to respiratory “cold and flu” viruses [3,5]. To correctly diagnose the underlying etiology and supposed treatment, certain scoring systems, and laboratory tests are available. Namely, the modified Centor score or rapid antigen test can help target antibiotic use by revealing an underlying infection with Streptococcus pyogenes (also known as Lancefield GABHS), which is one of the only agents that warrants an etiologic diagnosis and specific treatment [6-8]. In a clinical setting, however, it is difficult to differentiate between bacterial and viral pharyngitis. Some clinical features that strongly suggest a viral etiology include cough, rhinorrhea, hoarseness, oral ulcers, coryza, conjunctivitis, and diarrhoea [8,9]. Hence, even testing for GAS pharyngitis is not recommended for children or adults with these features, let alone prescription of antibiotics [9].

Despite this, one in two patients presenting to their physician in primary care with sore throat receive antibiotics [10]. Firstly, this leads to a significant economic impact as it puts a burden on the overall health care budget [1]. Secondly, this overconsumption of antibiotics is a major contributor to the development of a more sinister issue, antimicrobial resistance (AR) [11,12]. It has also been shown to increase patient visits as it medicalizes self-limiting conditions, which culminates in a vicious cycle of further visits for the same condition [13].

To eradicate these problems, there is an urgent need to transform the attitude of doctors regarding the antibiotic prescription. It is proven that primary care is still responsible for most antibiotics prescribed to people [11]. Therefore, young doctors, who form the crux of primary care, play a pivotal role in controlling and preventing the misuse of antibiotics [14]. To shed light on the root of this matter, it is vital to first evaluate the current practice by young doctors. An analysis of their practice in prescribing antibiotics can facilitate the development of appropriate interventions to improve antibiotic prescription and promote “antibiotic stewardship” globally [11].

METHODS AND MATERIALS

After acquiring permission from the Ethical Review Committee (ERC), Reference number - 121/2019, a cross-sectional study was conducted at Combined Military Hospital (CMH), Lahore, for 3 months starting 1st January 2019 till 31st March 2019. A list of all interns was acquired from the administration, and 80 interns who had 6 months or more of clinical experience were chosen by random, convenience sampling and included in the study after thorough consent. Interns will less than 6 months of clinical experience or those who did not rotate in filter clinics were excluded from the study.

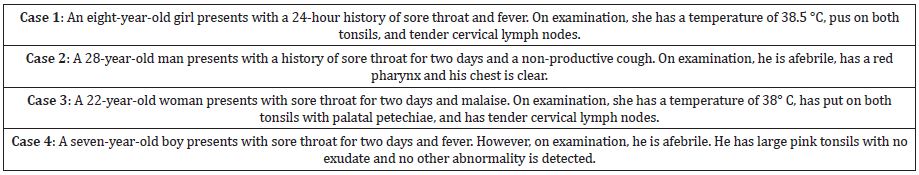

These interns were invited to fill out a questionnaire. The questionnaire was duplicated, after permission, from a 1994 study conducted in Australia [15,16]. The questionnaire used four clinical vignettes (Table 1) to assess the young physicians’ knowledge and clinical management plan to test and treat each case. An additional query on whether the doctors had heard about any scoring methods for sore throat was also asked (whether they had used it or not wasn’t recorded). Lastly, data was entered into SPSS v25, and descriptive statistics were drawn.

RESULTS

From the total 80 interns working at CMH Lahore (an urban, tertiary care hospital) who consented to participate in the study, there 58 females and 22 males, between the ages of 23 till 29. When queried about prior knowledge of scoring methods for sore throat. 20% claimed to have known some scoring method, while 80% had not known any.

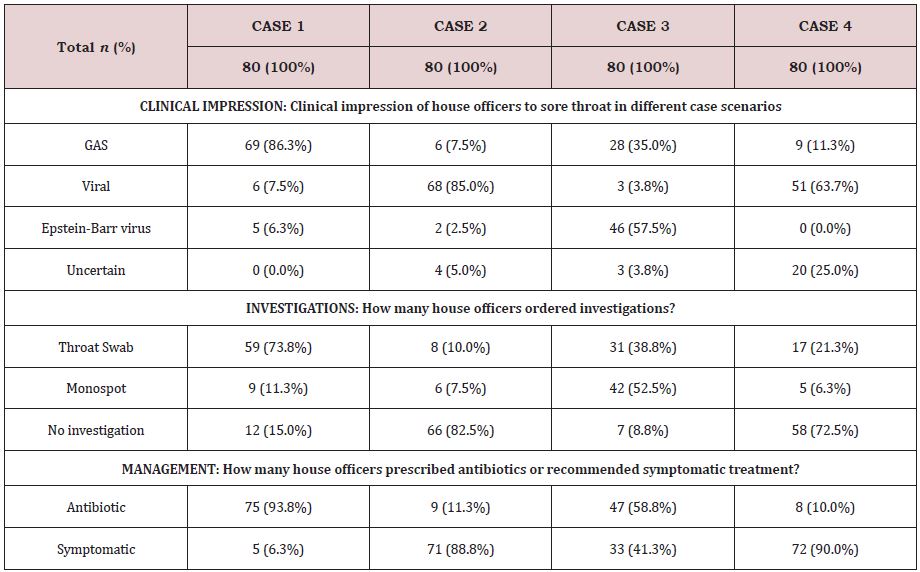

Moving on to results of the cases, for the first vignette (Case 1), 86.3% of interns had the impression that the presentation was owing to a bacterial infection, 73.8% doctors went ahead to test for GAS and a sweeping 93.8% prescribed antibiotics.

Cases 2 and 4 showed signs and symptoms suggestive of a viral upper respiratory tract infection (URTI). For case 2, 85% suspected the correct etiology. 63.7% of case 4 respondents did indicate a viral suspicion, but 25% were uncertain of the agent. This could’ve been the reason why a throat swab was sought by 21.3% interns, while for case 2, 82.5% interns preferred to not investigate further after establishing the correct diagnosis. Additionally, this shows that interns tested more in the case of the child as compared to the adult with a viral sore throat. In terms of treatment, 11.3% and 10% for cases 2 and 4, respectively, still chose to prescribe an antibiotic while symptomatic treatment remained the predominant choice in both scenarios. Lastly, case 3 showed a variable response. On the one hand, 57.5% reckoned Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) was the underlying agent, and hence the Monospot test was the popular choice amongst investigations (52.5%). On the other hand, a significant 35% suspected GAS, went for a throat swab. In terms of treatment, nearly half (58.8%) went on to prescribe antibiotics. Overall, there was no difference in prescribing rates between male and female doctors (Table 2,3).

DISCUSSION

The study aimed to analyse the perception of young interns towards antibiotic prescription for sore throat via analysis of their choices for 4 clinical vignettes (Table 1). The vignettes show presenting symptoms and pathophysiological signs of various exhibitions of sore throat. It’s a theoretical reflection as the cases were written scenarios rather than actual patients, which can believably suggest what happens in a clinical setting that leads to antibiotic misuse. From the 4 vignettes, case 1, a child with fever, sore throat, and physical findings of pus on tonsils and tender cervical lymph nodes is the only scenario that warranted antibiotic administration. This was correctly picked by 86.3% interns. However, the results revealed that a substantial proportion of respondents injudiciously prescribed antibiotics for latter cases. A considerable percentage of interns did so despite having a correct impression of the non-bacterial origin of the case. Previous studies like Nicholas et al. [16] hypothesized the cause of the inappropriate antibiotic prescription to be the lack of knowledge regarding pathophysiological features of sore throat and current recommendations and guidelines of treatment. We believe this is also the cause of incorrect antibiotic prescription by interns. However, contrary to our study, which focused on young doctors their cohort comprised of general practitioners (GP), who have more years of clinical experience in comparison. However, the prior studies concluded that GPs had a generally accurate assessment of features of sore throat, and the problem was in the choice of prescription.

Case 3 remained a diagnostic dilemma for interns, hence, there was a split choice between group A streptococcus (GAS) and infectious mononucleosis (IM) and consequently, about 50% doctors proceeded to do a Monospot. It is worthwhile to mention that IM should be suspected by all doctors in patients 10 to 30 years of age who present with sore throat and significant fatigue, palatal petechiae, and lymphadenopathy (18). Nevertheless, one striking comparison with the Danchin et al. [17] study was that more than 90% of GPs appropriately identified the viral origin of cases 2 and 4, while in our study this percentage was lower, i.e., 85% for case 2 and 63% for case 4. This depicts that while interns have a good pick of clinical signs pertinent to bacterial infections, e.g. pus on tonsils, fever, etc. their suspicion of viral etiologies is poorer than GPs. Hence, it can be established that as compared to GPs, interns do have a knowledge gap regarding the pathophysiological features, this is possibly due to their lesser clinical experience.

The Danchin et al. [17] study also revealed that for vignette 1, 89% of GPs opted for antibiotics. In our study almost 94% of interns advised antibiotics. However, there was a noticeable difference when it came to the choice of investigations, in our study, 73.8% of interns proceeded with a throat swab, while in the 2018 study [18] only 18.4% GPs chose this test. It can be concluded that young doctors abundantly investigate to back their judgment, perhaps because of diagnostic uncertainty. Another proof of this was found in results for case 2, where no GP (0%) in the study suggested any of the two tests (throat swab and Monospot) for the adult with a viral sore throat.

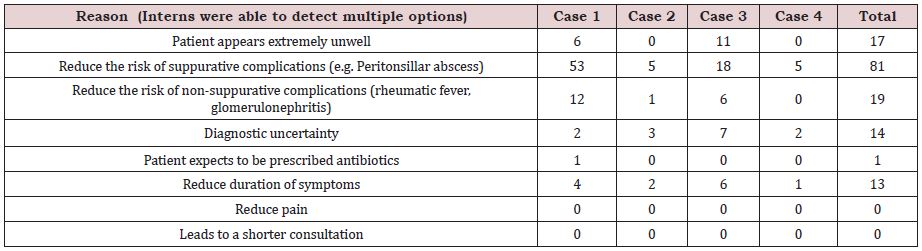

In addition to the above, when inquired about the motivation for antibiotic use, the common observation was that the majority of interns defended their advice of antibiotics by saying it would “prevent the risk of suppurative complications” (Table 3). This is opposed by The Sore Throat Guideline Group, 2012 who stated that prevention of suppurative complications is not a specific indication for antibiotic therapy in sore throat. They recommended that clinicians do not need to treat most cases of an acute sore throat to prevent quinsy, acute otitis media, cervical lymphadenitis, mastoiditis, and acute sinusitis. Therefore, there is room for further education of interns about clinical features as well as the latest management guidelines and scoring methods, e.g. Centro Score, especially in the context of increasing antibiotic resistance.

Altogether, some limitations must be discerned in this study. Firstly, the interpretation of our cohort cannot be extrapolated to young doctors as a whole, as the sample was chosen from graduates of the same medical college who have a rather similar learning curve, restricting the variability of the results. Secondly, although designed to replicate clinical scenarios the vignettes are written with a particular diagnosis in mind, this makes the symptomatology decipherable from the case itself. Whereas in a clinical setting, patients’ symptoms are often not as simply put, and neither is the detection of some clinical signs such as “palatal petechiae” always possible by young interns. Thus, this method of survey is not indicative of the actual clinical acumen of the interns.

CONCLUSION

Young primary care doctors frequently prescribed antibiotics despite the underlying etiology. It can be inferred that young doctors lacked knowledge of the pathophysiology of various presentations of sore throat, e.g., bacterial, viral, as well as the latest guidelines on antibiotic administration.

STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP

The authors confirm that the manuscript, the title of which is given, is original and has not been submitted elsewhere. Each author acknowledges that he/she has contributed in a substantial way to the work described in the manuscript and its preparation.

PLACE OF STUDY

Combined Military Hospital, Lahore, Pakistan (Outpatient department clinics).

SOURCE OF FUNDING

Combined Military Hospital, Lahore, Pakistan (Outpatient department clinics).

REFERENCES

- Shah R, Bansal A, Singhi SC (2011) Approach to a child with sore throat. Indian J Pediatr 78(10): 1268-1272.

- Kenealy T (2011) Sore throat. BMJ clinical evidence. BMJ Publishing Group.

- Orzell S, Suryadevara A (2018) Pharyngitis and pharyngeal: Fever, sore throat, difficulty swallowing. In: Introduction to Clinical Infectious Diseases: A Problem-Based Approach. Springer International Publishing; pp. 53-66.

- DuBose KC (2002) Group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Prim Care Update Ob Gyns 9(6): 222-225.

- Oliver J, Malliya WE, Pierse N, Moreland NJ, Williamson DA, et al. (2018) Group A Streptococcus pharyngitis and pharyngeal carriage: A metaanalysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 12(3).

- Pelucchi C, Grigoryan L, Galeone C, Esposito S, Huovinen P, et al. (2012) Guideline for the management of acute sore throat: ESCMID Sore Throat. Clin Microbiol Infect 18(Suppl 1): 1-28.

- Linder JA, Stafford RS (2001) Antibiotic treatment of adults with sore throat by community primary care physicians: A national survey, 1989- 1999. J Am Med Assoc 286(10): 1181-1186.

- Anjos LMM, Marcondes MB, Lima MF, Mondelli AL, Okoshi MP (2014) Streptococcal acute pharyngitis. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 47(4): 409-413.

- Shulman ST, Bisno AL, Clegg HW, Gerber MA, Kaplan EL, et al. (2012) Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of group a streptococcal pharyngitis: 2012 update by the infectious diseases society of America. Clin Infect Dis 55(10): e86.

- Mehta N, Schilder A, Fragaszy E, Evans H, Dukes O (2017) Antibiotic prescribing in patients with self-reported sore throat. J Antimicrob Chemother 72(3): 914-922.

- Costelloe C, Metcalfe C, Lovering A, Mant D, Hay AD (2010) Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal Publishing Group 340: c2096.

- Teng CL (2014) Antibiotic prescribing for upper respiratory tract infections in the Asia-Pacific region: A brief review. Malaysian Family Physician 9(2): 18-25.

- Llor C, Bjerrum L (2014) Antimicrobial resistance: Risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem. Ther Adv Drug Saf 5(6): 229-241.

- Hoque R, Mostafa A, Haque M (2015) Intern doctors’ views on the current and future antibiotic resistance situation of Chattagram Maa O Shishu Hospital Medical College, Bangladesh. Ther Clin Risk Manag 11: 1177-1185.

- Krishnakumar J, Tsopra R (2019) What rationale do GPs use to choose a particular antibiotic for a specific clinical situation? BMC Fam Pract 20(1):178.

- Carr NF, Wales SG, Young D (1994) Reported management of patients with sore throat in Australian general practice. Br J Gen Pract 44(388): 515-518.

- Tran J, Danchin M, Steer CA, Pirotta M (2018) Management of sore throat in primary care. Aust J Gen Pract 47(7): 485-489.

- Ebell MH (2004) Epstein barr virus infectious mononucleosis - American Family Physician 70(7): 1279-1287.

Article Type

Research Article

Publication history

Received date: September 22, 2020

Published date: October 07, 2020

Address for correspondence

Mohammad Abdullah, Combined Military Hospital, Pakistan

Copyright

©2020 Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science, All rights reserved. No part of this content may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means as per the standard guidelines of fair use. Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

How to cite this article

Mohammad A, Ayesha M, Manahil C, Sara Q, Arsalan N, Noreena I, Tehreem F. Approach of Intern Doctors to Antibiotic Prescription for Sore Throat. 2020 - 2(5) OAJBS.ID.000222.