Analysis of Pattern and Management of Mandibular Fracture in Children

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Mandibular fracture relatively less frequent in children when compared to adults, which may be due

to the child’s protected anatomic features and infrequent exposure of children to road traffic accidents. Mandibular

fracture occurs in children mostly green stick fracture.

Objectives: To assess the pattern of mandibular fracture in children and to compare the treatment results of two

techniques (Conservative and IMF).

Study design: Comparative Cross-sectional Study.

Setting: Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery Department, Liaquat University Hospital Hyderabad.

Duration: Study was carried out for two years Jan 2015 to Dec 2016

Methods: Mandibular fractures in children at Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department LUH were analyzed by

age, gender, etiology, type, site, occlusion time elapsed in reporting fracture and patients were treated by conservative

and IMF.

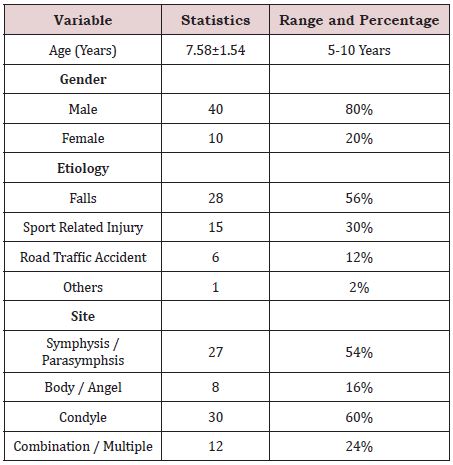

Result: A total of 50 patients with mandibular fractures diagnosed by clinically and radiographically was included

in this study. The mean age of the children was 7.58+1.54years. Out of 50 children, 80% boys and 20% girls were

reported 56% children were injured due to fall followed by 30% sports related injuries, 12% road traffic accidents and

2% were others. Fracture of condyle 60% (30/50) was more common in children followed by symphasis 54% (27/50).

Eighty percent cases were reported within 3 days while 12% were reported after 3 days. Intermaxillary fixation was

the commonest management modality.

Conclusion: The mean age of trauma was from 7.58+1.54years, 80% boys and 20% girls, commonest cause was

falls, condyle is most fractured site and IMF is the most appropriate treatment of mandibular fractures in children.

KEYWORDS

Fracture; Children; Intermaxillary fixation; Mandible

INTRODUCTION

Mandible Being largest, strongest, and peripatetic bone in the human frame with common risk to fracture, it is the tenth most common bone to fracture in human frame but in relation with face only it’s come on the second rank [1,2].will rewire their metabolism as one observes for tumor cells [6-10].

Either occurrence of mandibular fractures is possible separately or in combination with other bones of human frame, fracture site and severity totally depend upon the prominence, anatomy, mechanism, magnitude and direction of injury [3,4].

Adekeye study has defined that among children the facial fractures are fifteen percent lesser than that of the adults due to extensive physical activities carried out by the younger children [5,6].

Maxillofacial trauma is rare below the age of 5years (0.6-1.4%) and the chance of its happening is higher among school children [7-9]. In addition to that, during the puberty and adolescence occurrence of Maxillofacial Trauma is at uttermost [10].

Reason for the lower rate of facial fractures among children below the age of 5yrs is because of retruded position of face relative to the protective skull which resultantly reduces frequency of mid face and mandibular fractures with greater possibility of cranial injuries [11].

In Thoren’s study [11,12] (epidemiology of facial trauma) the common location of fracture in condylar region amongst the pediatric age group is around 60 and 72% of all fractures in children. According to Posnick the mandibular condyle is most injured area 55%, para-symphyseal region 27%, body 9% and angle 8% respectively.

Condyle mandibular fractures among young children are largely intracapsular and high neck fractures and that of low condylar fractures (fractures extending into the ramus) makes up only small portion [13].

As child grows, the chances of condylar fractures diminish, while fractures of other portion of body and angle increases. However, the fracture shape remains same in all ages of groups such as from the age of ten years old to the adult one.

Boys are more likely to be injured than girls because of physical activities. Male to female ratio is 3.4:1 [14]

Etiology of mandibular fracture varies in accordance with socioeconomic, educational and cultural environments along with sport related injuries and other sure falls [15]..

The handling of mandible pediatric fractures is entirely different from that of the adults [16]. The basic principles of management include re-establishing pre-injury occlusion and esthetics of the dentofacial complex with limited morbidity, without hindering future growth and development and without damaging the underlying dentition .and these younger patients also have the potential for restitutional remodeling as opposite to sclerotic and functional remodeling seen in adults. This is achieved by reduction of fracture site to its original anatomical alignment followed by stabilization with fixation [17].

Treatment modalities were divided into two groups:

• Patients treated with inter – maxillary fixation (IMF).

• Patients treated without inter – maxillary fixation

(Conservative).

Although, nearly all the mandibular fractures which does not cause supplant and pre trauma malocclusion are managed conservatively. (Research reflection is that, liquid to soft diet, with limited physical workout (sports) and analgesics. Moreover, the displaced but green stacked fractures except condyle require lessening and stopped for short period.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Cross-sectional study using convenience sampling technique was conducted in oral and maxillofacial surgery department, Institute of Dentistry Liaquat University Hospital Hyderabad. This study was carried out from January 2015 to December 2016. Fifty patients under the age of 5-10 years with history of mandibular fracture were included in this study. Diagnosis of fracture was made by clinical and radiographical examination. Patients age, gender, site, etiology, type, occlusion, and time elapsed in reporting fracture and all other data was recorded in prescribed Proforma. Fifty patients were divided to receive conservative treatment and intermaxillary fixation for short period of time.

RESULTS

A total of 50 children with history of mandibular fracture diagnosed clinically and radio graphically was included in this study. The average age of the children was 7.58±1.54 years. Out of 50 children, 80% boy and 20% girl were injured. 56% children were injured due to fall followed by 30% road traffic accident 12% and 2% were not identified cause of fracture.

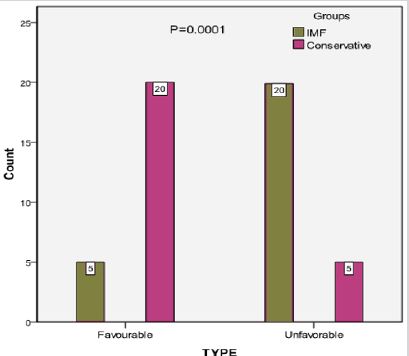

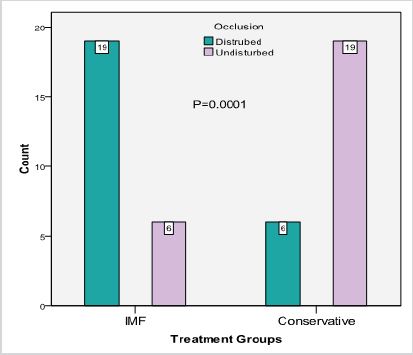

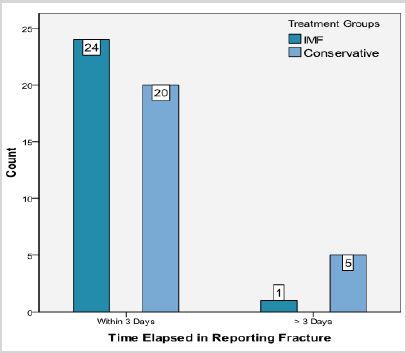

Fracture of condyle, 60% (30/50) was more common in children followed by symphsis 54% (27/50) as presented in Table 1. Favorable type was significantly high in conservative treatment than IMF treatment (80% vs. 16% p=0.001) as shown in Figure 1. Undisturbed occlusion was significantly high in conservative treatment than IMF treatment (76% vs. 24% p=0.0001) as presented in Figure 2. 20% cases were reported after 3 days of fracture in groups A and 4% cases were reported in group B (p=0.18) as presented in Figure 3.

DISCUSSION

The importance of mandible cannot be ignored while mastication, communicating and deglutition. The dominating factor of mandibular fracture among children has been concerned with the age of children 7.58+1.54 years [6] and that of their sports related activities. This conclusion has been drawn by the research studies conducted by Anderson [18]; Stylogiani [19]. The research has also acknowledged the fact that mandibular fractures are quite common in the boys (actual 80%/20%) than that of girls it is because boys by nature are inclined to physical games and bit curious. The renowned researchers like Lizuka [20] have admitted the fact that boys receive more mandible fractures than that of the girls. The Alboosi [21] have perceived that since boys engage themselves in the out- door games and the girls remain behind the doors. The different results have had been observed that substantial manifestation of mandibular condylar fractures process among girls is moderate, the study was conducted by Zachariades [22]; Zerfowksi [23]. The aetiological factor in the mandibular fractures remain dominant. The average incidents of accidents (falls 56%, sports 30%). Motor vehicle accidents 12% and horse kick counts at 2% of all mandibular fractures. However, the latest statistics may vary in the different countries like African nations and the South American states where the gun and drugs culture have altered the results. The statics however have been endorsed by the certain researchers such as oji Cheema [24]; Amaratunga [25]. Moreover, that mandibular fractures among children of pre-school age dare more common. The pre-school children remain at home around daytime and keep congruit their efforts in climbing or touching luminating things. Their innocent activities lead them often falls and ultimate results mandibular fractures. With increasing age and the children involve in outdoor activities and skip themselves from parental supervision.

Although Zachariades [22] Papavassilou with Koumouura F of the opinion in their papers that the MVA and the modern transport services have contributed greatly in mandibular fractures among the children. The studies further comprehend that there are literally two types of fracture, favorable and unfavorable Statistically, there are 52% cases of favorable type of fractures and 48% of unfavourable. This research has also been able to say that condylar fractures are the most common by 60% followed by symphysis 54% (27/50), combination/ multiple fractures (more than one side of mandible fractures) is 24%reported and body and angle fracture is 16%.

The results of Reil [26]; McGuiri [27], also confirmed our findings and it concluded that trauma force was applied in the symphyseal region, resulting indirect fractures of the condyle with or without fractures in the symphseal region. While contrasting results were found from the studies of Oikarinen [28]. Al-Aboosi [21] where majority of fractures were observed in the mandibular body. But here in our results body fractures were the fourth most common site. Also, the contrasting results in studies carried by Ugboko [29]; Olasoji [30]. Symphyseal and para-symphseal was the commonest site affected in contrast to condyle and body fractures. The results are reported for distributed occlusion is 50%, and undistributed occlusion is 56%. The study has also revealed that more than 88% of the patients- child- visit hospital for reporting the fractures within three (3) days. However, a small number 12% of cases of mandibular fractures are reported after the elapsed of three days period. However in this comparative study, in which 50 patients were observed with mandibular fracture, half of those patients were given conservative treatment and the other half were given IMF treatment for 1 to 2 weeks and ideally IMF is considered best treatment for growing child this research supports by other authors Oji Chema [24]; Remi Marianowsk [31].

CONCLUSION

The research study conducted on 50 children and draw our attention to that mandibular fractures occur due to physical activities of children. In such circumstances, when the incidents of such mandibular fractures are reported treatment is divided in two phases. One is emergency treatment and other hand is long term treatment is advised which includes analgesics and soft diet. With a view to achieve quick desired results, the children are advised to limit their physical activities during the treatment duration. It is concluded from this research that the children provided intermaxillary fixation (IMF) had proper occlusion at the end of treatment compared to the conservative treatment.

REFERENCES

- Sirimaharaj W, Pyungtanasup K (2008) The epidemiology of mandibular fractures treated at Chiang Mai University hospital: A review of 198 cases. J Med Assoc Thai 91(6): 868-874.

- Fornesca RJ, Walker RV, Betts NJ, Barbar HD (1997) Oral and Maxillofacial trauma. 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Saunders, USA

- Khan A, Khitab U, Khan MT, Salam A (2010) A comparative analysis of rigid and non-rigid fixation in mandibular fractures: A prospective study. Pak Oral Dent J 30: 6267.

- Rahim AU, Warraich RA, Ishfaq M, Wahid A (2006) Pattern of mandibular fractures at Mayo hospital, Lahore. Pak Oral Dent J 26(2): 239-242.

- Khatri A, Kalra NA (2011) conservative approach to pediatric mandibular fracture management: Outcome and advantages. Indian J Dent Res 22(6): 873-876.

- Saoji S, Agrawal S, Bhoyar A, Shrivastava S, Mishra A, et al. (2015) Management of mandibular fracture in pediatric patient with cap splint: A case report. Int J Dent Clin 7: 33-34.

- Haug RH, Foss J (2000) Maxillofacial injuries in the pediatric patient, Oral surg Oral Med Oral Radiol Endod 90(2): 126-134.

- Sardana D, Gauba K, Goyal A, Rattan V (2014) Comprehensive management of pediatric mandibular fracture caused by an unusual etiology. Afr J Trauma 3(1): 39-42.

- Kocabay C, Ataç MS, Oner B, Güngör N (2007) The conservative treatment of pediatric mandibular fracture with prefabricated surgical splint: A case report. Dent Traumatol 23(4):247-250.

- Priya Vellore K, Gadipelly S, Dutta B, Reddy VB, Ram S, et al. (2013) Circummandibular wiring of symphysis fracture in a five-year-old child. Case Rep Dent 930789.

- Aizenbud D, Hazan-Molina H, Emodi O, Rachmiel A (2009) The management of mandibular body fractures in young children. Dent Traumatol 25: 565-570.

- John B, John RR, Stalin A, Elango I (2010) Management of mandibular body fractures in pediatric patients: A case report with review of literature. Contemp Clin Dent 1(4): 291-296

- Morrow BT, Samson TD, Schubert W, Mackay DR (2014) Evidence-based medicine: Mandible fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg 134(6):1381-1390.

- Steed MB, Schadel CM. (2017) Management of pediatric and adolescent condylar fractures. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 25(1): 75- 83.

- Lukas J, Rambousek P (2001) Injuries of the upper and middle thirds of the face. Analysis of the cause of injury. 140(2): 47-50.

- Ferreira PC, Amarante JM, Silva PN, Rodrigues JM, Choupina MP, et al. (2005) Retrospective study of 1251 maxillofacial fractures in children and adolescents Plastic reconstrsurg 115(6): 1500-1508.

- Hassan SG, Shehzad M, Butt AM, Shams S, Ali N (2013) Management of mandibular fracture in pediatric patients at LUH Hyderabad Med forum 24(3): 63-66.

- Anderson PJ (1995) Fracture of the facial skeleton in children, Injury 26: 47-50.

- Stylogianni L, Arsenopoulos A, Patrikiou A (1991) Fractures of the facial skeleton in children, Br J Oral Maxillo Surg 29(1): 9-11.

- Lizuka T, Thoren H, AnninoJr DJ, Hallikainen D, Lindqvist C (1995) Midfacial fractures in pediatric patients. Frequency, characteristics, and causes, Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 121(2): 1366-1371.

- Al-boosi, K Perriman A (1976) One hundred cases of mandibular fractures in children in Iraq. Int J Oral Surg 5(1): 8-12.

- Zachariades N, Papavassiliou D, Koumoura F (1990) Fractures of the facial skeleton in children, J Craniomaxillofac Surg 18151-53.

- Zerfowski M, Bremerich A (1998) Facial trauma in children and adolescents, Clin Oral Investig 2: 120-124.

- Oji C (1998) Fractures of the facial skeleton in children: a survey of patients under the age of 11 years, J Craniomaxillofac Surg 26(5): 322- 325.

- Amaratunga NA (1988) Mandibular fractures in children: A study of clinical aspects, treatment needs and complications. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 46: 637.

- Reil B, Kranz B (1976) Traumatology of maxillofacial region in childhood (statistical evaluation of 210 cases in the last 13 years) J Max-fac Surg 4: 197-201.

- McGuiri WF, Salisbury PL (1987) Mandibular fractures. Arch Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg 113(3): 71-74.

- Oikarinen VJ (1969) Malmstrom jaw fractures. Suom Hammaslaak Tomin 65(1): 95-111.

- Ugboko V, Odusanya S, Ogunbodede E (1998) Maxillofacial fractures in children: an analysis of 52 Nigerian cases Pediatric Dental Journal 8: 31- 35.

- Olasoji HO, TahirA, Bukar A (2002) Jaw fractures in Negerian children: an analysis of 102 cases. Central African Journal of Medicine 48:109-112.

- Remi M, Christine MC, Gael P, Soizick P, Joseph-Andre J (2003) Mandibular fractures in children: long term results. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolarygol 67: 25-30.

Article Type

Research Article

Publication history

Received date: March 03, 2020

Published date: March 11, 2020

Address for correspondence

Salman Shams, Senior Lecturer Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery, Pakistan

Copyright

©2020 Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science, All rights reserved. No part of this content may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means as per the standard guidelines of fair use. Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

How to cite this article

Tahira S, Samreen N, Mir Jam T, Salman S, Preesa S. Analysis of Pattern and Management of Mandibular Fracture in Children. 2020 - 2(2) OAJBS.ID.000151